Article MT240

John MacKay Wilson

and his Tales of the Borders

Foreword:

When Mike Yates sent me the following article, he advised me: I have a long article that I wrote a couple of years ago about the writer John McKay Wilson, who wrote 'Tales of the Borders'. I had not considered you as a possible publisher but, as you have recently published an article on Jack in the Green (which is not really about music) and a CD of stories, I thought that you may be interested in the Wilson piece.

Wilson is little known in England - he was from Berwick-upon-Tweed - but there is quite a revival of interest in him in Scotland and several Scottish storytellers are using his tales as a source. Many of his stories were based on folktales or folksongs, such as Polworth on the Green. I am not too certain whether this is for you but, as I say, there is a lot of new interest in Wilson, and researchers may be drawn to Musical Traditions and the article, which is, I believe, unique. Ed.

Introduction

Old tales I heard of woe or mirth,

Of lovers' slights, of ladies' charms,

Of witches' spells, of warriors' arms;

Of patriot battles, won of old

By Wallace wight and Bruce the bold;

Sir Walter Scott: Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field

The writer John MacKay Wilson lies buried beneath a memorial stone in Tweedmouth churchyard, on the south bank of the Tweed estuary. The stone now stands in a state of disrepair and is in urgent need of restoration. When Wilson died in 1835 he was considered to be an important writer, one who's Tales of the (Scottish) Borders were almost as popular as the works of Sir Walter Scott and James Hogg. And yet, today, he is little known and, like his memorial stone, has almost faded into obscurity. Wilson was born in 1804. Frail from birth, he died thirty-one years later, at a time when his works, especially his stories, were becoming well-known throughout England and Scotland and, indeed, in many of the countries where the Scots had settled.

The writer John MacKay Wilson lies buried beneath a memorial stone in Tweedmouth churchyard, on the south bank of the Tweed estuary. The stone now stands in a state of disrepair and is in urgent need of restoration. When Wilson died in 1835 he was considered to be an important writer, one who's Tales of the (Scottish) Borders were almost as popular as the works of Sir Walter Scott and James Hogg. And yet, today, he is little known and, like his memorial stone, has almost faded into obscurity. Wilson was born in 1804. Frail from birth, he died thirty-one years later, at a time when his works, especially his stories, were becoming well-known throughout England and Scotland and, indeed, in many of the countries where the Scots had settled.

This short piece chronicles all that is known today about Wilson's brief life. It lists all of Wilson's stories that appeared in the Tales and discusses Wilson's sources and influences, including folk songs and folk tales. This is followed by an account of what happened to the Tales following Wilson's untimely death and gives short biographical details of the writers whose work appeared in later issues of the Tales. There is also a listing of the principal published versions of Wilson's Tales, together with one of Wilson's stories, The Seven Lights, which did not appear in the Tales.

John MacKay Wilson's Tales tell of a different age, one where there was no television, radio or cinema, and one where people had to find their own entertainment, often sitting at home together, listening to stories that were read from books, local papers or weekly magazines. It is now, perhaps, difficult for us to understand just how important such stories were to their readers. But, important they were!

Copies of John MacKay Wilson's Tales may still be found in second-hand and antiquarian bookshops throughout the Borders today. The stories are written in a style that may now be unfamiliar to many readers, but they are still well worth reading. I only hope that this short treatise may encourage others to seek out and enjoy Wilson's stories as much as I do.

John MacKay Wilson - the man and his work

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead, Who never to himself hath said, This is my own, my native land!

Sir Walter Scott: The Lay of the Last Minstrel

You have all heard of the Cheviot mountains. They are a rough, rugged, Majestic chain of hills, which a poet might term the Roman wall of Nature; crowned with snow, belted with storms, surrounded by pastures and fruitful fields, and still dividing the northern portion of Great Britain from the southern. With their proud summits piercing the clouds, and their dark rocky declivities frowning upon the glens below, they appear symbolical of the wild and untamable spirits of the Borderers who once inhabited their sides.

From John MacKay Wilson's story The Vacant Chair

John MacKay Wilson, the son of William Wilson, (died 4th April, 1844) a sawyer or millwright, from Duns, in Scotland, and Jane Wilson (died 1844), was born on 15th August, 1804 in Tweedmouth, Northumberland, a village on the south side of the Tweed Estuary and a few hundred yards from the ancient Border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed. He had two brothers and one sister and all the children were educated at the local Presbyterian Church school by a schoolmaster named Elliot. England was then at war with France and there was social unrest across the country. James Good's Berwick Directory of 1806 lists no persons named Wilson then living in Tweedmouth, though it may be that Good was actually reprinting a list that had been compiled in 1801, and William Wilson may not then have been living in Tweedmouth. According to John Tait, “Tweedmouth, where the river Tweed meets with the ocean, consists of a clump of houses many of them with red tiled roofs, and from the Berwick side, looking as if the ancient borough had burst the boundaries of its encircling wall, and thrown an outpost across the Tweed, by the long, low, narrow, and quaint bridge (1164 feet in length), with fifteen arches, which here spans the mighty Border river. On closer inspection, Tweedmouth is found to be astir with sea-faring men, with boat-building yards, and works of boiler-makers and agricultural implement makers. There is also the great salmon-fishing industry, which employs many hands. It is a confused, busy, breezy, and somewhat odoriferous place…It is natural to suppose that in his leisure hours Wilson wandered often by Tweedmouth Moor, or up the sides of the river to Norham on the one side or Paxton on the other. Doubtless he had pleasure in surveying the landscape, as it can be grandly seen from various coigns of vantage in the immediate neighbourhood. He could easily see the outline of the Lammermoors, the top of lofty Cheviot, Hume Castle, and the Eildons three; and fancy, doubtless, carried his thoughts still farther to the towns and hills famous in Border story, even as far up as the Bield where:

Tweed, Annan, and Clyde,

Come out o ae hill-side. 1

1

“His early days were spent in peace and happiness under his parental roof, and were marked with a kind of native thirst for knowledge.” 2

2

One of Wilson's poems, The Tweed near Berwick, which was unpublished during Wilson's lifetime, concerns the youthful love for nature and place that he discovered during his walks along the Tweed's side.

On thy banks, classic Tweed, still my fancy shall wander,

Though far from the Land of the Thistle and thee,

And follow thy course to its latest meander,

The place of my birth where thou meetest the sea.

'Though the memory of those early friendships did cherish,

Will fade and is fading, thou still art the same,

For though dear to remembrance young feelings must perish

And the friends of our youth will exist but in name.

But there is a language in thee, sweeping river,

A voice in the woodlands that shadow thy braes,

A home and a heart by thy side that shall ever

Be one with existence, be dear to my lays.

'Midst the daydream of boyhood, ere glowing ambition

Had sung the fond thrillings of beauty and love,

Thy banks were my study - my only tuition

The sounds of thy waters, the coo of thy dove.

Stream of maturity, can I forget thee

When my birthplace's threshold thy waters will lave?

Forget thee! When Nature's omnipotent set thee

To wash the green sod by my forefather's grave?

Yet if these were forgot thou art witness with heaven

Of my vow on the breath of thy murmurs conveyed,

When, pure as the fountain, confiding was given

To me the fond heart of my Favourite Maid.

In this, deep and keenly, my soul's dearest feeling

Now tells me that thou art remembered indeed,

For to think of the Maid of my Heart is revealing

A tale that revisits the banks of the Tweed. 3

3

John Mackay Wilson was eleven years old when the French wars ended at the battle of Waterloo. It was also the time when Wilson obtained his first job with a firm of printers owned by William Lochhead of High Street, Berwick-upon-Tweed. Lochhead appears to have specialized in printing Bibles and history books and John became an apprentice printer, working in Lochhead's Stoddart's Yard premises. Apparently John was a keen reader and was able to further his education by reading the books that Lochhead printed. When he was fifteen years old, Lochhead printed 100 copies of one of John's early poems A Glance at Hinduism. The poem begins with a dedication that is taken from the Biblical Psalms, 'The dark places of the earth are full of the habitations of cruelty', and concerns itself with the Indian practice of suttee, where a widow was burned on the funeral pyre of her late husband. Clearly the practice was found to be abhorrent by Wilson, who offered the following advice:

Shed Gospel light upon Hindostan's sons

And dissipate their darkened mental gloom.

Make pagan folly (cruel, delusive dream)

Be seen by them in all its odious forms.

Lead them from penance to the prayers of faith

And faith in Christ, in Christ God's only son.

Wilson's Christianity is well to the fore in this poem. Throughout his life he supported the Methodist Church and was especially friendly with James Everett, a Manchester-based (later Newcastle-based) bookseller and Methodist preacher. Later, in 1834 when Wilson was living in Berwick, he was able to say to Everett:

I am holding out to your admirers here that they in all probability will have the pleasure of hearing you preach here in the course of the Spring or Summer -and I am resolved you shall preach, - we won't let you leave Berwick without doing so. 4

4

A few months later, Wilson made the following observation to Everett:

Had my paper and time permitted, I intended to have said something about the dissensions which seem to be arising in your most respected body. I don't like the conduct of the Ashton man, he is too much of voluntary for me; while on the other hand, so far as I can perceive the Rev Jabez Bunting and others seem too strongly to lean to episcopacy - I never like to hear the subject mentioned. 5

5

At the time that he wrote A Glance at Hinduism Wilson was courting a girl called Sarah Sanderson, who lived at Gainslaw Hill, near the junction where the Tweed meets the Whitadder, some couple of miles to the west of Berwick. However, Sanderson rejected Wilson in order to marry a Gentleman's manservant who lived nearby; and so Wilson left his printer's apprenticeship and headed south to London where, like many others, he no doubt sought fame and fortune. Sadly, both were conspicuous by their absence, and Wilson was forced to sleep rough in various parks and open spaces. Some writers have stated that Wilson spent his last two shillings buying a ticket to see the famous actress Sarah Siddons. 6 Mrs Siddons final stage performance was on 9th of June 1819, when Wilsion would have only been fifteen years of age, but she did continue to give public readings until her death in 1831, and it may have been at one of these events that Wilson saw Mrs Siddons. It is thought that Wilson did find employment in London with a firm of lawyers, where he worked copying legal documents, although this work did not last for long. Several of Wilson's later stories contain incidents of poverty and are probably based on his own experiences. Luckily Wilson was rescued by James Sinclair, an agent for Lloyds at Berwick, who happened to be visiting London. Walking one day in a park, Sinclair saw the name 'John Mackay Wilson' written above an alcove. After some searching, Sinclair found Wilson and was able to offer financial help so that Wilson could return to Tweedmouth, where he married Miss Sarah Gladstone, who was described as 'a lady of humble means'. Wilson then moved to Edinburgh where he worked on the staff of the Literary Journal. In 1829 his melodrama The Gowrie Conspiracy was performed in Edinburgh to some acclaim. It was soon followed by other stage plays, such as The Highland Widow and Margaret of Anjou. Wilson then wrote The Poet's Progress, The Border Patriots and The Sojourner, “a Poem of considerable length, in the Spenserian stanza but not being able to meet with a publisher, he commenced writing his 'Lectures on Poetry', with 'Biographical and Individual Sketches', which he completed in three manuscript volumes. These lectures he continued to deliver, with various success, in the principal towns of Scotland and England, till, about three years ago, he rested from his wanderings in his native village, among his friends and early associates”.

6 Mrs Siddons final stage performance was on 9th of June 1819, when Wilsion would have only been fifteen years of age, but she did continue to give public readings until her death in 1831, and it may have been at one of these events that Wilson saw Mrs Siddons. It is thought that Wilson did find employment in London with a firm of lawyers, where he worked copying legal documents, although this work did not last for long. Several of Wilson's later stories contain incidents of poverty and are probably based on his own experiences. Luckily Wilson was rescued by James Sinclair, an agent for Lloyds at Berwick, who happened to be visiting London. Walking one day in a park, Sinclair saw the name 'John Mackay Wilson' written above an alcove. After some searching, Sinclair found Wilson and was able to offer financial help so that Wilson could return to Tweedmouth, where he married Miss Sarah Gladstone, who was described as 'a lady of humble means'. Wilson then moved to Edinburgh where he worked on the staff of the Literary Journal. In 1829 his melodrama The Gowrie Conspiracy was performed in Edinburgh to some acclaim. It was soon followed by other stage plays, such as The Highland Widow and Margaret of Anjou. Wilson then wrote The Poet's Progress, The Border Patriots and The Sojourner, “a Poem of considerable length, in the Spenserian stanza but not being able to meet with a publisher, he commenced writing his 'Lectures on Poetry', with 'Biographical and Individual Sketches', which he completed in three manuscript volumes. These lectures he continued to deliver, with various success, in the principal towns of Scotland and England, till, about three years ago, he rested from his wanderings in his native village, among his friends and early associates”. 7

7

John MacKay Wilson returned to Berwick in 1831 and began helping to edit The Border Magazine. Many of Wilson's poems and lectures were included in the early editions, together with his story The Vacant Chair, which was later to become the first of a series of Tales of the Borders. Apparently it was Wilson's favourite story and is the only one of his Tales that was printed in America as a separate pamphlet.

In February, 1832, Wilson had moved to 15, Byrom Street in Manchester. His financial situation was still precarious, as this letter, dated 4th February, to James Everett, shows:

I trouble you with this under much perplexity and painful feeling ... Now as I have stated before I can go I must sell the copyright of my work. I wrote to my friend Pringle upon the subject and he and his friends are to assist me; but in order to accomplish my object as early as I wish, they consider it necessary that I should be in London to push the business personally. Now I know this is necessary - that I must do so at whatever sacrifice. But I may have to remain two or perhaps three weeks in London before I obtain a settlement. And upon the cheapest calculation which I can make, I find it would require about two pounds more than I am in possession of. It is absolute agony for me to request you if you could befriend me with the loan of this sum till I am enabled to pay you on my return. Let the pain of my feelings and the pressure of my situation be my excuse in making a request at which my very soul blushes. 8

8

Wilson continued:

I leave Mrs Wilson here and am most anxious to set off on Monday night if possible. I will have considerable literary backing; and have again written to Jerdan, announcing my intention and the nature of my visit requesting also his influence, and reminding him of the kindness with which he offered to aid in promoting my views about six years ago. But though I should sell it at the Minerva Press price of £15 a volume, it must go. But I hope its superiority over other works of its kind will save it from such a fate. I care not when they publish it, providing they give part payment in hand. What I do I must do speedily. They call upon me to come to Berwick, and with all my anxiety I am unable to comply with the demand, and without your aid to enable me to effect it by the only means in my power, I fear my hope must perish. I suppose you will not get this till Monday - so do let me have your answer as early as possible, - I would have called on you, - but I could not - it is with pain I have written this, - and spoken it, I could not. If you can serve me in this matter, I will not talk of gratitude - for I have this day found, that words of kindness and gratitude are a false and a hollow sound. Believe me I would not forget your friendship. Let me have your answer as early as possible, and Believe to be yours in much confusion, But sincerity. 9

9

Wilson was clearly aware that things would not necessarily go his way in London:

Colburn and Bentley have informed me that owing to their present engagements being so numerous they could not undertake the publication of my work with any hope of doing it justice, until next season. This is as useless and profitless a hope to me as preaching repentance to a dead man. 10

10

He also makes mention of his poor health, the reason why he apparently had to give up lecturing to the public for the time being. “Had I been able still to Lecture, this might have done, but I feel that to risk doing so would almost be wilfully to destroy my own life.” 11 But things were soon to change for the better. By February, 1832, Wilson had been approached to become Editor of the weekly Berwick paper, The Berwick Advertiser:

11 But things were soon to change for the better. By February, 1832, Wilson had been approached to become Editor of the weekly Berwick paper, The Berwick Advertiser:

Until I obtain a settlement with a publisher, I cannot go to Berwick to undertake the Editorship of the paper without incurring obligations which would make me rather the slave of the proprietor than the conductor of the journal. This I could not do and must avoid. But the prospect which that situation holds out of being always at home having a certain income, and independence, with a large portion of literary leisure, makes me tenfold more anxious to embrace the offer of it than ever I was to obtain anything on this earth. My brother is to manage it for two or three weeks till I can arrive; but in political matters he is wholly unskilled. 12

12

Wilson returned to London in early February, 1832, and later told Everett that things had not changed there:

I found the London market at a standstill, and it is an understood thing among the trade that scarce any work will be brought out until after the settlement of the reform question. All the principal writers are of necessity resting upon their oars, and waiting for the turning of the tide. And there is not one of the second rate and inferior houses reckoned safe. Three publishers who have seen the MSS. have engaged to make me offers for it as soon as the state of things will justify them in doing so. But at present all say they could not give any price. The three are Bull, - Kidd, - & Cochrane. I could not see Jerdan, but wrote him again. 13

13

In other words, Wilson, still being short of money, agreed to take Editorship in Berwick, although he would have to lecture in order to raise some money for his journey, or, at least, for a part of his journey. “I must be in Berwick in about a fortnight or less, - and it will cost me much labour to do that as we shall walk to Newcastle - and I will stop in Leeds for a day or two and deliver my Lectures, and then wither walk it or coach it.” 14

14

Wilson had returned from London to Manchester on the 25th February, 1832, where he was offered the job as Editor of The Manchester Chronicle. Wilson clearly wanted to take up this offer, but felt duty-bound to move to Berwick, having given his undertaking to edit the Berwick paper:

Just after my return Mr Catherall sent for (me) yesterday afternoon, and informed me I have his place as Editor of the Chronicle. Had this been told me a month ago, - but I have affixed my signature to the articles regarding the Berwick paper, - and cannot draw back without self-reproach and disgrace. However Mr Catherall says he will not leave until June, & I believe he has spoken of me to Mr Wheeler, the salary would be three guineas a week. Now should I find after a trial at the Berwick paper that its advantages would not equal this, - I could leave it according to agreement by giving a month's notice. Now I will from time to time let you know my feelings and prospects thereon, which you can communicate to Mr C. so that the second string of the bow be not broken, but kept unstrung for a time, - and if I find it would be advisable, I could about June find my way back to Manchester. Yet health - and home are powerful magnets to draw me to the North and keep me there. 15

15

Berwick, it must be said, was not the most ideal of places for a person suffering from ill health. There were frequent outbreaks of cholera, for example, and this account, taken from a report in 1849, no doubt reflects the conditions that existed when Wilson returned to Berwick in 1832:

“The borough of Berwick-upon-Tweed is not so healthy as it may be, on account of undrained streets, imperfect privy accommodation, crowded courts, houses, room-tenements, and large exposed middens and cesspools … Excess of disease has been distinctly traced to the undrained and crowded districts, to deficient ventilation, and to the absence of a full water-supply, and of sewers and drains generally.” 16

16

In March, 1832, Wilson became editor of The Berwick Advertiser, a paper that included an original political leader each week - to be written by Wilson - alongside national and foreign news. During periods when news was scarce, Wilson would include one of his own stories, in verse or prose. Again, Wilson was unwell when he moved into the Editor's chair, although, by November of that year, his health appeared to be on the mend:

You know I was ill when I left Manchester, but it grew worse - much worse and for the first four or five months of my Editorship the thread of life quivered as if every hour it might be expected to break asunder. I grew unable to walk across the room, or to lie save upon one side. Every person thought I was dying - but myself. Many of their cheering prophecies reached my ear, and though I knew my days were numbered I did not believe that they had from my ghostly looks and wasted form been able to read the number. At length I began to recover, - and I did recover most rapidly. Yea when I again felt health in my veins and gasped in the pure air of heaven amidst my native fields, where the larks poured down their tide of song, I seemed to swallow life, air, music and all! - Everything teemed with delight, - I felt it in my veins, in the breeze, upon my cheek, in the leaves, the trees, and the waving grass, - I never felt the gowan beneath my foot before! The sensation was enough to repay the sickness of years. 17

17

But Wilson now had a purpose in life and he began to find some of the recognition that had so far eluded him:

As I understand you still get the paper, you must tell me how you like it, and wherein you think it might be improved. It was in a miserable condition when I took it in hand. Talent or spirit it never had, and its sale was rapidly decreasing. Within a fortnight I obtained them about a hundred additional subscribers, - its circulation rose higher than it ever was during the five and twenty years of its existence and it continues weekly to increase. In fact when I took the helm of their wreck, I found her timbers rotten and floundering among rocks, - refitted her and steered her into the haven of profit and popularity. For this service you will no doubt think the proprietors are generous and grateful. If they are they have neither shown it nor said it. They fear me rather than love me. You may ask how can this be? - With the public they have become as nobody, and in town and country it is called Mackay Wilson's paper. Now my salary mainly was to rest on the success of the paper at the end of twelvemonths - there is but three months of the twelve to run, and they have never hinted directly or indirectly at that part of our bargain. However I shall say nothing till the three months be out; but I would have been more satisfied with some token of generosity on their side. Indeed I have never had a single paper since I became Editor without paying sevenpence for it, the same as another subscriber! In the entire management of it however they have never ventured to interfere with me in the slightest! - I have urged them to get me new types, and make it the one half larger but as it is it is bringing them in a handsome profit at a cheap rate and they cannot find it in their hearts to expend a shilling on it. If this narrow spirit continues - they and I must shake hands, - the old types and the older press are theirs, but the readers are mine, and if they encourage me not according to my exertions, next year I would feel it my duty to become printer and Editor of an opposition journal, - for no one shall grow fat on the sweat of my brains, unless I am an equitable sharer in the profits. 18

18

Wilson clearly had plans for the local newspaper. Here he is asking Everett if he may include the latter's poem The Mount in a special edition of the paper:

What are you doing? Is the “Mount” finished? Respecting it, I have a favour to ask, - will you send me and allow me to print in my columns, the stanzas descriptive of the scene from the Mount, - and also the stanzas which describe the Maniac? - You really must. Without leave you will perceive I have printed the only two stanzas I had. I expect pieces from Hogg, Pringle and several others, and intend to make a show number like the Athenaeum. 19

19

At one point, towards the end of November, 1832, Wilson had considered taking on the failing Border Magazine as part of his work-load. This was the magazine that he had previously worked for in 1831.

The Border Magazine will voluntarily give up the ghost next month. Some wish me to take it up as a purely literary publication, under the title of “Wilson's Border Magazine”. I will think twice - yea thrice about it before I do - for I have not so much time to spare as you would imagine, and after paying publishers & the printer, it would leave very little for me. I think I shan't. 20

20

And, if that was not enough, Wilson was also working on his own books:

I am at present on the extreme tenter hooks of anxiety; for four weeks I have been expecting a letter every day from my friend Mr Pringle to say how much he has got for my novel. It must sing or swim before the next year. I have three volumes more ready to bring out on the back of it. But if this bargain is not to my satisfaction, I shall print the others here. 21

21

But, life was not all work. Wilson did seem to have some sort of private life and he was still in good health, despite an outbreak of cholera that had occurred in Berwick.

I am very comfortable here, in as far as we have enough to satiate every reasonable desire. But periodicals are old before I see them. Books are difficult to come at - that is useful books - for the libraries are filled with trash; - and literary society there is not even the shadow of. Save at two public dinners, and I have not been in the company of either one kind or another public or private since I arrived here. I have had many invitations, - but I have no taste for their society and it is my humour to appear as “a voice crying in the wilderness” … My “Vacant Chair” has appeared a year behind its time in the “Forget Me Not”. I had applications from three others, but from the weak state of my health at the time I was unable to comply. I never enjoyed such excellent health as I do now, and I have to thank my Maker that the months of illness endured have taught me to feel how delightful health is. - I need not inform you we have cholera here, - but I believe it is now extinct, or very nearly so. The deaths I believe amounted to about 260. 22

22

1832 was also the year that the Reform Act was passed and Wilson used the Advertiser's pages to promote his support for reform. This was a period of English history that saw many people questioning the status quo. A young MP, Thomas Babington Macaulay wanted political reform to protect the rule of law “from the exercise of arbitrary power”. During the period 1760 - 1810 no fewer than sixty-three new capital offences had been added to the statute books. According to Macaulay, “People crushed by law have no hopes but from power. If laws are their enemies, they will be enemies to laws”. 23 Macaulay was probably aware of Oliver Goldsmith's earlier couplet:

23 Macaulay was probably aware of Oliver Goldsmith's earlier couplet:

Each wanton judge new penal statutes draw,

Laws grind the poor, and rich men rule the law …

According to the English historian E P Thompson, “In the decades after 1795 there was a profound alienation between classes in Britain, and working people were thrust into a state of apartheid whose effects - in the niceties of social and educational discrimination - can be felt to this day. England differed from other European nations in this, that the flood-tide of counter-revolutionary feeling and discipline coincided with the flood-tide of the Industrial Revolution; as new techniques and forms of industrial organization advanced as political and social rights receded. The 'natural' alliance between an impatient radically-minded industrial bourgeoisie and a formative proletariat was broken as soon as it was formed.” 24 One glaring form of inequality was the fact that only a handful of land-owners had the right to vote. The 1832 Reform Act was the first stage in rectifying this inequality.

24 One glaring form of inequality was the fact that only a handful of land-owners had the right to vote. The 1832 Reform Act was the first stage in rectifying this inequality.

But, during all the time spent working for Reform, Wilson was still able to find time to compose some of his best poems, including the poem Midnight, which was published in 1832 in The Literary Gazette of London:

The sea is silent, and the winds of God

Stir not its waters; on its voiceless waves

Thick darkness presses as a mighty load,

Weighing their strength to slumber. O'er earth's graves

One lonely star is watching; and the wind,

Benighted on the desert, howls to find

Its trackless path, as would a dying hound.

The thick clouds, wearied with their course all day,

Repose like shrouded ghosts on the black air,

Or, in the darkness having lost their way,

Await the dawn! 'Tis midnight reigns around -

Midnight, when crime and murder quit their lair -

When maidens dream of music's sweetest sound,

And mother weeping, breathe the yearning prayer.

Wilson spent the next years editing the Advertiser and, presumably, working on more of his own writings. On January 1st, 1834, he was able to send copies of his new work, The Enthusiast, to his subscribers:

With this comes the “Enthusiast”. I hardly know how I shall get the copies forwarded, as we have no coach direct to Manchester, - but I will try to get the parcel away somehow or other and it must take its chance….I have been exceedingly fortunate with the publication. The copies which I have sent out on order on Saturday and to-day amount to above sixty pounds, - but it puzzles me to know how I am to get the money collected being from nearly three hundred individuals in different parts of the country, but all respectable … He is a silly man who cannot form an opinion of his own works and to you I do not hesitate to say that I think it a volume of good poetry. But you must judge for yourself, and in the Eclectic, Imperial and Manchester papers, say whatever honesty dictates putting friendship out of the question - I would be ashamed to call myself your friend if I were capable of speaking of your next work when it comes to hand in any other manner … I am certain of gaining some money by the publication, and I expect a portion of popularity. 25

25

Wilson was not alone in his admiration for this work. “Within these few weeks I have received very complementary letters respecting the “Enthusiast” from H.R. the Duke of Sussex, old Earl Spencer, the Earl of Tankerville, Lord Howick, Sir Rufus Donkin and others.” 26 But, as ever, there were still problems with the owners of the Advertiser: “The “Annual humbugs” have jerked me this year and not paid me yet.”

26 But, as ever, there were still problems with the owners of the Advertiser: “The “Annual humbugs” have jerked me this year and not paid me yet.” 27

27

Nor was this the only problem to trouble Wilson:

I never see the “Athenaeum” now nor the “London Literary Gazette” here until they are more than two months old, therefore I must apply to my friend Wenett who can see them every week and as I shall send copies to both of them to-day, though they may not reach them for a fortnight, I know thou will feel as much anxiety to know what these Reviewers will say of me as I do myself, - and whether they speak good or evil, cause what they say to be copied into a letter for me and send it by post. I must ask you to do the same with the notices in the Eclectic &c. for I have no means of seeing them. 28

28

Occasionally, though, Wilson did find compensation whilst living so far from London. “I was on my way to a sale of old Books, and amongst others put up (for sale) was a perfect and excellent folio edition of Barker's Black Letter Bible, printed in 1611. There was a good deal of competition but I was the successful bidder. You will perhaps pity my Bibliomania, - but you must not be too severe - I would rather want victuals for a day than a Book that I desire, and my library already is assuming no mean appearance.” 29 Although, in general, Wilson was becoming dissatisfied with his life in Berwick:

29 Although, in general, Wilson was becoming dissatisfied with his life in Berwick:

Everything here is excessively dull, - money, like the coat of our old friend Jack the Giant Killer is invisible and our farmers and several of our most respectable tradesmen, equipping themselves in his seven league boots, are stalkinhg across the Atlantic. I am afraid it will take fifty years to come, thoroughly to cure poor old England. Nevertheless, the Advertiser goes on encreasing in prosperity and popularity, and I have the satisfaction of enjoying the favour of all classes for twenty miles round. The entire edition of the “Enthusiast” with the exception I believe of about a dozen copies is sold of, but not the one half are yet paid for. 30

30

Wilson was also beginning to feel uneasy about his job as Editor of the Advertiser and of his future in general:

My situation as Editor here obtains for me a large portion of respect and a considerable share of flattery. It is however no sinecure, and were the duties not such as I delight in, they would be laborious. The recent improvements require more labour, and have encreased the circulation, but they have not encreased my salary, nor have I asked an increase or intend to ask it. I believe I am the worst paid of any Editor in Britain - but I do not think I cut the shabbiest appearance. The salary, however, such as it is, places a person of my habits and 'family'in a state of comfort - above want and in comparative independence. Yet in some things I feel the will without the means. Now, the actual proprietor of the paper, is a youth about sixteen years of age, who is now at the High School or College in Edinburgh receiving an education that may qualify him to be his own Editor. It is no secret that he when old enough is to take the management of the Advertiser upon himself. The public laugh at this and say the paper would not stand a quarter of a year without me. I certainly saved it from the very verge of ruin, and made it one of the best paying provincial papers in the country - But the young gentleman may be clever and please the public as well as me; and if in a year or two, he and his friends think him qualified to conduct the paper, they will be right in doing so. But I would be what I am not were I to toil for them until they might say to me, “we thank you for your faithful services and Master Henry will henceforth conduct the Advertiser himself." No. I have now entered on my third year, and if it please Heaven to spare me, and nothing better offer in the interim, I will continue Editor for another year, - but not longer. 31

31

One possibility considered by Wilson was to return to legal work:

I have long been desirous of fighting my way to the bar. But the path is beset with difficulties. I would have three, if not five years of privation and expense before me and my wife, and after all I might remain for five years more a briefless barrister. After weighing well the subject, therefore, I have almost abandoned the idea. 32

32

If not the bar, then there was the possibility of a relocation to the New World:

You are aware that the newspapers in the Canadas are absolutely trash and in the United States they are little more than respectable. With the recommendations that I could take with me, I do not think I would be long in finding an Editorship, and if I once had one, I should take care to be but a short time in being both proprietor and Editor of an American newspaper. As either the Canadas or the States are now peopled, this would not be lowering myself; and in point of talent I would not have the competition to contend with that I have in this country. Neither is patronage there an overshadowing need. If therefore, nothing better cast up between this and this time twelvemonths, and I enjoy the blessing of health till then I believe I shall try my fortune beyond the Atlantic. 33

33

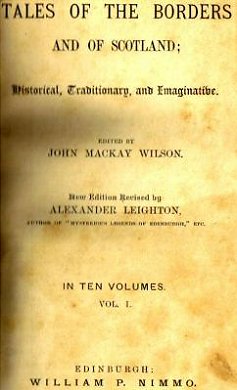

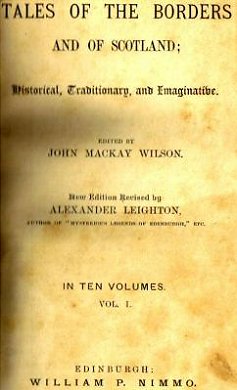

But, on Saturday, 18th October, 1834, Wilson's determination to remain in Berwick was confirmed when the Berwick Advertiser announced that on the 8th of November G Richardson of Berwick would be publishing the first issue of Historical, Traditionary, and Imaginative Tales of the Borders, by John MacKay Wilson. The issue would cost three-halfpence. The Tales were to be published weekly and there was also to be a monthly edition, containing all the stories from the previous month's weekly issues. The monthly edition was to be sold for 6d. It was planned that the work would be of ninety-six number, or twenty-four parts, that could be bound as two volumes.

Wilson again wrote to his friend Everett, seeing assistance in seeking out an agent for the Tales in Newcastle, Everett having moved north from Manchester to Newcastle:

I am about … to publish my Tales of the Borders in cheap weekly numbers and for this purpose I wish to appoint an Agent in every town on the Borders, and also in all the principal Towns of the Kingdom. I therefore require an agent in Newcastle … My terms are - threepence a shilling where more than fifty copies are ordered, - where below fifty Twopence. Settlement monthly with an additional discount of Two and a half per cent where payment is made within a month from the date of the Monthly account. From the accounts reaching me from all quarters the speculation promises to be very successful, though at first I shall have some uphill work. 34

34

The first issue of The Tales appeared on the 8th November and contained two stories, The Vacant Chair and Tibby Fowler. Two thousand copies were printed, but before the week was out a second edition had to be printed to meet the unexpected demand. Two weeks later sales had reached four thousand. On the 3rd January, 1835, when issue nine appeared, it was stated that the printers were unable to meet demand, the printing then being for five thousand copies per weekly issue. A second edition of the earlier copies had sold out and a third edition was in course of preparation. By the end of January the print run was for six thousand copies and by the middle of March it had risen to eight thousand copies. On the 21st March a fourth edition of the earlier issues was announced for circulation in the south of England. It was to be published by Houlston & Sons, of 65, Paternoster Row, London, who were also appointed the selling agents for London and the south.

It was soon apparent that, in common with other contemporary writers, many of Wilson's Tales were of a moralizing and didactic nature. In the seventeenth issue we find this short note from Wilson. “This tale has been written from the circumstance of The Tales of the Borders having already been adopted as a lesson-book in several schools”.

When the twenty-sixth issued appeared on 2nd May - containing the story The First and Second Marriage - the following statement, by Wilson, was included: “It is now half-a-year since the Tales of the Borders commenced, and their success may excuse the author in saying a few words concerning them. There never was an instance of what is called a provincial publication meeting such a reception from the public; and it is only one or two metropolitan publications that can boast of the same circulation, and that only within the last two or perhaps three years. The Tales of the Borders were commenced at about two thousand weekly. Many then said that quantity would never sell. But they not only are now nearly two thousand every week, but of many of the earlier numbers more than seventeen thousand have been sold; and from proposals that have been made to the author by London book-sellers, to circulate the work throughout England, Scotland, and Ireland, within a month the weekly circulation will not be below THIRTY THOUSAND.”

In fact, at that time this was quite a staggering number of copies to be published each week. And it should be remembered that Wilson was also continuing to edit the Berwick Advertiser each week. As I said before, Wilson had also thrown himself into the Reform debate and, by the summer of 1835, the strain of all this work had begun to take its toll on Wilson. There seems to be a tradition among some writers who have previously written about Wilson to say that he was a heavy drinker and that this was the reason for much of his ill health, and was a cause of his early death. And yet there seems to be little, if any, evidence for this. Could a person who supported the Methodist cause really be a drinker? In October, 1834, Wilson had written to the Methodist James Everett praising the beauties of nature and of his plans for their joint venture to visit the Scottish poet James Hogg during the following spring:

I wish you had been with me the week before last. My eyes looked over and beyond you. I made a tour over and around the Cheviots. You shall see a description of it some day. On the extreme top of the highest mountain, I was enveloped in a thick, tangible cloud, - I could not see three feet before me, you might have cut it with a knife. I got bewildered and in the end when I again got below the clouds, found myself in Scotland when I imagined I had been pursuing the nearest way to Wooler. Before the clouds enveloped me however, I had some glorious views. Beneath me in the middle distance, crowned with sunbeams, while transparent clouds floated below, I beheld the Mount, - Everett's Mount, or if you will have me so to write it Alnwick Mount. To the horizon on the south east Gateshead fell was distinctly visible. To the south west appeared the shadowy forms of the mountains of Cumberland. To the north the Lammermuirs, - to the north west the cleft Eildons - and others of the classic hills of Scotland - You say we shall go to see Hogg, - with all my heart. I will meet you at Wooler - if you choose the spring for our Excursion, - and though a little circuitous, we will go by the Cheviots. The beauty - the magnificence - the variety - the savage sublimity of the scenery will amply repay the toil. 35

35

There has been some confusion in the past regarding John MacKay Wilson and the well-known Scottish writer James Hogg (1770 - 1835). One of Hogg's good friends was James Wilson (1785 - 1854), a writer who, in 1820, was elected Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University, and some commentators have confused this John Wilson with John MacKay Wilson. In 1832 John MacKay Wilson produced an article on James Hogg for the Literary Gazette of London. 36 Hogg was then visiting the Metropolis and the article begins with this introduction:

36 Hogg was then visiting the Metropolis and the article begins with this introduction:

At the time when the Etterick Shepherd is, happily for his present enjoyment, and, we trust, happily for his permanent interest, exciting so much of the attention and receiving the caresses of all ranks in the London world, the following sketch of him can hardly fail to gratify our readers. We are indebted for it to Mr John Mackay Wilson; himself a young author, and a candidate for some portion of the fame he has so honestly assigned to his fellow-borderers, “fast by the river Tweed”.

Wilson begins his piece with the words:

JAMES HOGG, one of the most extraordinary individuals that has appeared in the literary world, was born on the 26th of January, 1771, in a wild pastoral region called Ettrick Forest, in the south of Scotland;- a region uneven, rugged, and romantic, - occasionally beautiful, - always imposing, and often untameable in aspect as the spirit of its early inhabitants.

At one point Wilson gives a most detailed physical description of Hogg:

In stature he is about five feet six. His person is round, stout, and fleshy, with a slight inclination towards corpulency. His usual dress is a gray, or rather what is termed a pepper-and-salt coloured coat, composed of cotton and woollen, and made wide and flowing, after the manner of a sportsman's, but longer than such are generally worn; with trousers of the same, and yellow vest, or, upon a gala-day, the gray trousers are exchanged for nankeen. His face is ruddy, healthy, good-natured, and stamped with unassuming modesty and simplicity … His eyes are of a bluish gray, laughing and lively. His brow broad, open, and untouched by age, is still smooth; his hair is of a yellowish hue; he is active, strong-built, and athletic, and appears not less than ten years younger than he is in reality.

And yet, despite such a detailed picture of Hogg, there are no personal anecdotes within the article. Hogg's interests are listed thus:

He is an indifferent farmer - a tolerable astronomer - as good an angler as a poet - an archer anxious to excel.

But, somehow or other, Wilson's laudatory piece fails to show Hogg as a person that Wilson actually knew. As the introduction says, Wilson was 'a young author'. His piece was written two years before the weekly Tales of the Borders began to be published and so it can hardly be expected that he would then have been moving in circles that brought him into contact with James Hogg, or any of Hogg's literary friends, such as Sir Walter Scott. 37

37

Nor does it seem likely that Wilson and Everett made their proposed journey to visit Hogg in the spring of 1835, as Wilson's health was again giving cause for concern. Finally, on 3rd October, 1835, the following obituary appeared in the Berwick Advertiser:

“This morning, in the 31st year of his age, and after an illness of three weeks, Mr John M Wilson, during several years editor of this journal, and author of various compositions in prose and poetry, which are familiar to the public. Mr W. acquired the status in society which he occupied at the time of his decease by dint of his own exertions; and thus added another to the honourable examples of persons who have overcome difficulties, and bettered their condition in the world. His efforts in the cause of Reform will be remembered long. To facilitate the progress of liberal opinions on subjects both of general and local interest was the constant aim of his editorial labours; and to every movements in this quarter, which identified itself with the liberties and comforts of the people, he lent a strong impulse by his presence and powerful appeals.”

Wilson, who left a widow, Sarah, but no children, was buried in Tweedmouth Churchyard, opposite the church-door, and Sarah later erected a large memorial stone at the head of the grave. Today this memorial is in a state of poor repair. According to an extant local tradition, shortly after Wilson's coffin was lowered into its grave an irate young woman flung an issue of the Tales on top of Wilson's coffin, shouting as she did so, “Here. Tak yer lees wi ye”. It is thought that she believed her father to have been the subject of one of Wilson's stories. 38

38

Wilson's Tales of the Borders

“Each weekly number came forth in small quarto size, with a blue cover and the arms of Berwick on the title-page. It was customary to have the Tales read aloud in the family circle; and often the reading was accomplished only in broken accents with intermittent sobs, while the sleeves of the auditors were much occupied in brushing away the sympathetic tears.” 39

39

The Tales of the Borders had been written and published by Wilson himself. 40 Each week he had prepared an edition of the Tales (several issues containing more than one story) and, at the time of his untimely death, he had produced the following seventy-five stories:

40 Each week he had prepared an edition of the Tales (several issues containing more than one story) and, at the time of his untimely death, he had produced the following seventy-five stories:

Issue

#

1. The Vacant Chair. Tibby Fowler. My Black Coat; or, The Breaking of the Bride's China.

2. We'll Have Another. The Soldier's Return. The Red Hall; or, Berwick in 1296. Grizel Cochrane: A Tale of Tweedmouth Muir.

3. Sayings and Doings of Peter Paterson.

4. The Prodigal Son. Sir Patrick Hume: A Tale of the House of Marchmont. Charles Lawson.

5. The Orphan. Squire Ben. The Fair.

6. Archy Armstong. The Widow's Ae Son. An Old Tar's Yarn. The Death of the Chevalier de la Beauté.

7. The Procrastinator. Ups and Downs; or, David Stuart's Account of his Pilgrimage.

8. The Adopted Son: A Tale of the Times of the Covenanters. The Sisters; a Tale for the Ladies.

9. The First-Foot.

10. The Persecuted Elector; or, Passages from the Life of Simon Gourlay. The Order of the Garter; A Story of Wark Castle.

11. The Seeker. The Siege; a Dramatic Tale.

12. Lottery Hall.

13. The Cripple; or, Ebenezer the Disowned. The Broken Heart; a Tale of the Rebellion.

14. The Leveller.

15. The Bride. The Henpecked man.

16. The Smuggler.

17. The Dominie's Class.

18. The Doom of Soulis. The One-Armed Tar.

19. The Poacher's Progress. I Canna be Fashed; or, Willie Grant's Confessions.

20. The Royal Bridal; or, The King may come in the Cadger's Way.

21. The Faa's Revenge; A Tale of the Border Gipsies.

22. The Solitary of the Cave.

23. Ruben Purves; or, the Speculator.

24. Midside Maggie; or, The Bannock o' Tollishill. The Sabbath Wrecks; a Legend of Dunbar.

25. The Poor Scholar.

26. The First and Second Marriage.

27. The Guidwife of Coldingham; or, The Surprise of Fast Castle. Leaves from the Diary of an Aged Spinster.

28. The Adventures of Launcelot Errington and his nephew Mark; a Tale of Lindisferne.

29. The Twin Brothers.

30. Judith the Egyptian; or, The Fate of the Heir of Riccon. The Deserted Wife.

31. The Unbidden Guest; or, Jedburgh's Regal Festival. The Simple Man is the Beggar's Brother.

32. The Covenanting Family.

33. The Unknown.

34. The Fugitive.

35. Leaves from the Life of Alexander Hamilton.

36. The Wife or The Wuddy.

37. Willie Wastle's Account of His Wife.

38. The Festival. Polworth on the Green.

39. Bill Stanley; or, A Sailor's Story.

40. The Recollections of a Village Patriarch.

41. The Whitsome Tragedy.

42. Perseverance; or, The Autobiography of Roderic Gray. The Irish Reaper.

43. Edmund and Helen; a Metrical Tale.

44. Roger Goldie's Narrative; a Tale of the False Alarm.

45. Trials and Triumphs.

46. The Laidley Worm of Spindleston Heugh; a tale of the Anglo-Saxons. Johnny Brotherston's Five Sunny Days. The Hermit of the Hills.

47. The Minister's Daughter.

48. The Minister's Daughter. (Continued)

49. The Minister's Daughter. (Concluded)

John Mackay Wilson's Tales are subtitled “Historical, Traditionary and Imaginative”. But what exactly does this mean? Are the stories contained in the Tales folktales or traditional legends? Are they stories based on historical events? Or are they imagined stories composed by Wilson himself? Clearly, as we shall see, some of the stories are based on known legends, songs and tales, but, in the majority of cases, things are not always clear cut. In the story Polworth on the Green Wilson says:

Nowhere are traditions more general or more interesting than upon the Borders. Every grey ruin has its tale of wonder and of war. The solitary cairn on the hillside speaks of one who died for religion, or for liberty, or belike of both. The every schoolboy passes it with reverence, and can tell the history of him whose memory it perpetuates. The hill on which it stands is a monument of daring deeds, where the sword was raised against oppression, and where heroes sleep. Every castle hath its legends, its tales of terror and of blood, “of goblin, ghost or fairy." The mountain glen, too, hath its records of love and war. There history has let fall its romantic fragments, and the hills enclose them. The forest trees whisper of the past; and, beneath the shadow of their branches, the silent spirit of other years seems to sleep. The ancient cottage, also, hath its traditions, and recounts “The short and simple annals of the poor." Every family hath its legends, which record to posterity the actions of their ancestors, when the sword was law, and even the payment of rent upon the Borders was a thing which no man understood; but, as Sir Walter Scott saith, “all that the landlord could gain from those residing upon his estate was their personal service in battle, their assistance in labouring the land retained in his natural possession, some petty quit-rents of a nature resembling the feudal casualties, and perhaps a share in the spoil which they acquired by rapine." Many of those traditions are calculated to melt the maiden's heart, to fill age with enthusiasm, and youth with love of country.

We may also suggest that Wilson's Tales also relied heavily on the works of Sir Walter Scott, a fact previously noted by Basil Skinner, an Edinburgh academic:

In the detail of his plots, Wilson every now and then reveals his debt to Scott. The prison interview between Grizel Cochrane and her father recalls that between Effie and Jeannie Deans, and there is an even closer parallel between the cursing of the Laird o'Clennel by Elspeth Faa, Queen of the Gypsies, and the similar cursing of the Laird of Ellangowan by Meg Merrilees … The greatest significance of Wilson's Tales, however, lies in their continuance of the nostalgic tradition that Scott had developed in his early novels. This had two aspects: firstly, a recourse to domestic life as a source of narrative interest; and secondly, a compulsion to record a vanished society in a moment of change. 41

41

Wilson's story The Deserted Wife begins with the sentence. “The following tale was communicated to me when in Dumfriesshire, in the year 1827, by an old and respectable lady, who was herself the subject of it." Did Wilson therefore 'collect' this story from the old lady, or was he using an artificial device in order to make his own composition sound more truthful?

In the story of The First and Second Marriage we find a similar introductory technique:

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said a venerable-looking, white-headed man, accosting me one day, about six weeks ago, as I was walking along near the banks of the Whitadder; 'ye are the author of the 'Border Tales,' sir - are ye not?”

Not being aware of anything in the “Tales of the Borders” of which I need to be ashamed, and moreover being accustomed to meet with such salutations, after glancing at the stranger, with the intention, I believe, of taking the measure of his mind, or scrutinizing his motive in asking the question, I answered - “I am, sir.”

“Then, sir” said he, “I can tell ye a true story, and one that happened upon the Borders here within my recollection, and which was also within my own knowledge, which I think would make a capital tale.”

I think it fair to say that Wilson's Tales are, for the most part, the product of Wilson's own imagination. Some stories are based on actual events, but, in all of Wilson's Tales, we can clearly see that the stories are Wilson's own. Two stories, The Red Hall; or, Berwick in 1296 and The Siege; a Dramatic Tale, are based on historical events that occurred in Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1296 and 1333 respectively, and Wilson would no doubt have been familiar with John Fuller's History of Berwick upon Tweed which documents both events. 42 Likewise, he would have known of the Faa family of Gypsies, who are central to the story The Faa's Revenge; A Tale of the Border Gipsies, some of the Faa's having settled in Berwick and Tweedmouth.

42 Likewise, he would have known of the Faa family of Gypsies, who are central to the story The Faa's Revenge; A Tale of the Border Gipsies, some of the Faa's having settled in Berwick and Tweedmouth. 43

43

Willie Wastle's Account of His Wife, based on the poem by Burns, is told by Willie himself and, following a couplet from the poem, begins thus:

“It was a very cruel dune thing in my neebor, Robert Burns, to mak a sang aboot my wife and me,” said Mr William Wastle, as he sat with a friend over a jug of reeking toddy, in a tavern near the Bridge-end in Dumfries, where he had been attending the cattle market.

In a footnote to the story, Wilson mentions Allan Cunningham's Life of Burns (1833), a book that Wilson clearly knew. Another book is also, indirectly, referred to in the story of The Adopted Son. A verse from the ballad The Battle of Philiphaugh is printed, again as a footnote, and this verse is identical to one printed in Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802 - 03).

Tibby Fowler is also based on a song of that title. According to Wilson:

“All our readers have heard and sung of 'Tibby Fowler o' the glen;' but they may not all be aware that the glen referred to lies within about four miles of Berwick.”

The tune Tibby Fowler o' the Glen is known to date from at least 1742, although the earliest set of words can only be dated some thirty years later, in 1776, when David Herd published them. The song is also included in later collections that predate Wilson's death and the words to the song were printed on a number of Scottish broadsides. 44 In none of these instances is mention made of a Berwick setting for the song. It would seem, therefore, that it was Wilson himself who placed the song into a setting that was familiar to him. Wilson also introduces the story of Polworth on the Green by mentioning an earlier song of the same name.

44 In none of these instances is mention made of a Berwick setting for the song. It would seem, therefore, that it was Wilson himself who placed the song into a setting that was familiar to him. Wilson also introduces the story of Polworth on the Green by mentioning an earlier song of the same name. 45

45

Another tale, The Order of the Garter; A Story of Wark Castle, is also based on an actual happening, although Wilson has made it into a local story set at Wark Castle, on the Tweed near Coldstream. The Order of the Garter is an honour presented by the monarch as a reward for military merit. According to legend, the award was created by King Edward III when he retrieved a garter dropped by the Countess of Salisbury and, although Wark Castle was once owned by the Salisbury family, there is nothing to suggest that this was the actual scene of the incident.

Sadly, The Laidley Worm of Spindleston Heugh; a tale of the Anglo-Saxons is nothing of the sort. Supposedly written in Latin c.1270 by one Duncan Frasier, the ballad tells of a jealous step-mother who turns her step-daughter into a dragon. It was, like the poems of Ossian, a fake, written by the Reverend Robert Lambe (1712 - 95) of Norham. Did Wilson know this? Perhaps not, because he continues to perpetuate the supposed myth in a footnote to the story.

Interestingly, there is little mention of fairyland in any of Wilson's stories. Witches, wizards, fairies or brownies are hardly seen in the Tales. Surely the story of Thomas the Rhymer, who lived near Melrose and who was taken down into fairyland by the Queen of the fairies, would have been known to Wilson. But there is nothing told about Thomas in the Tales although the belief in fairies was still common in Wilson's days. 46 It may be that Wilson's Christianity stopped him from writing about such matter, although strangely enough there is one tale, The Doom of Soulis, which concerns a wizard. The last Lord Soulis lived in Hermitage Castle, a few miles to the south of Hawick. The castle stands in a barren, wind-swept landscape, and it is little wonder that this story should have developed in such a place. Again, Wilson's story is based on a local legend about Soulis and his meetings with the Devil. According to the legend Soulis was finally overcome by his enemies, who wrapped him in sheets of lead before boiling him alive in a cauldron. In Wilson's telling of the story we find a detailed account of how Soulis raised the Devil by means of animal sacrifices. We are also told that Soulis is attacked by people bearing rowan branches, a well-known means of protection against witches. Wilson may have picked this up from Lambe's

The Laidley Worm of Spindleston Heugh where:

46 It may be that Wilson's Christianity stopped him from writing about such matter, although strangely enough there is one tale, The Doom of Soulis, which concerns a wizard. The last Lord Soulis lived in Hermitage Castle, a few miles to the south of Hawick. The castle stands in a barren, wind-swept landscape, and it is little wonder that this story should have developed in such a place. Again, Wilson's story is based on a local legend about Soulis and his meetings with the Devil. According to the legend Soulis was finally overcome by his enemies, who wrapped him in sheets of lead before boiling him alive in a cauldron. In Wilson's telling of the story we find a detailed account of how Soulis raised the Devil by means of animal sacrifices. We are also told that Soulis is attacked by people bearing rowan branches, a well-known means of protection against witches. Wilson may have picked this up from Lambe's

The Laidley Worm of Spindleston Heugh where:

They built a ship without delay,

With masts of the rowan tree,

Because it is known:

… that witches have no power,

Where there is rowan-tree wood.

Finally, one story that is attributed to Wilson, The Seven Lights, deals with premonitions of death. It is similar in some ways to the stories of second-sight that we find in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. The story does not appear in Wilson's Tales and is attached as Appendix 3.

The Tales of the Borders - following Wilson's death

He has left a widow … to depend on the profits of his works for the comforts necessary for her till she sink to rest with him in the grave. Nor are her prospects dark if those who cheered her on in his literary labours still stand by her. His materials are not yet exhausted, and “tales yet untold” are in reserve to keep alive his memory and soothe as far as earthly comforts can her widowed heart…Under the management of Mr James Wilson, her brother-in-law, and Mr Sutherland of 12 Calton Street, Edinburgh, who is now publisher, we trust to see her reap the full reward of his genius and toild whose last hours she sweetened. 47

47

Despite a frantic search, following Wilson's death, there were, in fact, no new stories to be found in manuscript form. But the public were clamouring for more Tales and so Wilson's friend James Sinclair, by then a Berwick solicitor, drove out to see Dr Carr of Coldingham, who had previously written The History of Coldingham Abbey. Sinclair persuaded Dr Carr to contribute material to the next issue, number 50, and on the 10th October, only a week after Wilson's death, it was announced that “the Border Tales for the future will be published for behoof of the Widow of John Mackay Wilson, Berwick, by John Sutherland, 12 Carlton Street, Edinburgh. From the Steam-Press of Peter Brown, Printers, Edinburgh. Stereotyped by D Stevenson." Coincidentally , one of John Mackay Wilson's brothers, also called John Wilson, was working as a printer for John Sutherland. John was then aged 26 years and he too died suddenly thirteen months after his elder brother's death.

Sutherland continued to print new editions of the Tales with contributions from several writers. As part of the agreement Sarah Wilson obtained an annuity for her husband's copyrights, which left her financially stable. At first James Wilson, another of John Mackay Wilson's brothers, agreed to help Sutherland. Later, however, Sutherland approached Alexander Leighton to write stories and edit future issues. Leighton was born in Dundee in the year 1800. He studied medicine at Edinburgh University before considering a legal career. However, Leighton seems to have loved writing and he soon found that all his time was taken over by his literary work. In 1864 Leighton produced Mysterious Legends of Edinburgh, a collection of stories published by William P Nimmo. The ten stories are: The Ancient Bureau, The Brownie of the West Bow, Deacon Macgillivray's Disappearance, John Cameron's Life Policy, Lang Sandy Wood's Watch, A Legend of Halkerston's Wynd, Lord Braxfield's Case of the Red Nightcap, Lord Kames's Puzzle, Mrs Corbet's Amputated Toe, and The Strange Story of Sarah Gowanlock. None of these stories appear in Tales of the Borders. He was also the author of The Romance of the Old Town of Edinburgh, The Men and Women of History, Jepth's Daughter and The Tangled Yarn. In 1870 Leighton became a victim of 'a creeping paralysis' which forced him to remain at home and out of sight of his friends. He died in his house in George Street, Edinburgh, on the evening of December 24, 1874.

The Tales soon changed in character when Leighton took over the editorship. The stories were no longer confined to the Border region, but came from all over Scotland. The Tales of Grace Cameron, for example, were set in the West Highlands, while The Widow of Dunskaith was set in Cromarty.

At one point, Sutherland asked another contributor, David Macbeth Moir, known as 'Delta', to take over the editorship. Moir (January 5, 1798, Musselburgh - July 6, 1851, Dumfries) was a Scottish physician and writer. Having obtained a degree in medicine from Edinburgh University in 1816, he entered into partnership with a Musselburgh doctor, where he practiced until his death. Moir contributed to a number of magazines, including Blackwood's Magazine, often signing his contributions with the Greek letter 'Delta'. He was the author of a number of books, including Life of Mansie Waugh, Tailor (1828), Outlines of the Ancient History of Medicine (1831) and Sketch of the Poetical Literature of the Past Half Century (1851). However, Moir felt unable to help Sutherland and referred him to his brother, who was then a clerk in the bank of Sir William Forbes. Young Moir mentioned the matter to his friend Walter Logan, adding, “I have seen Sutherland; but what do you think? He offers me money. I don't write for money." “Don't you?" said Logan “then I will." Walter H. Logan is today, perhaps, best known for his book A Pedlar's Pack of Ballads and Songs (Edinburgh. 1869). A resident of Berwick-upon-Tweed, he was a good friend of the contributor James Maidment - the Pedlar's Pack being dedicated to Maidment, who had lent most of the broadsides to Logan that were used in the book. Logan did take over the reins, contributing tales that filled fifteen complete issues. It was Logan who also persuaded his friends James Maidment and Theodore Martin to contribute to the Tales.

James Maidment (1794, London - 1879, Edinburgh) was called to the Scottish bar, following his education at Edinburgh University. He became the chief authority on Scottish genealogical cases. Maidment was also a keen amateur collector of Scottish folksong and folklore. He published a number of important ballad collections, including A New Book of Old Ballads (Edinburgh, 1844), Scotish Ballads and Songs (Edinburgh, Glasgow & London. 1859), Scotish Ballads and Songs, Historical and Traditionary 2 vols. (Edinburgh, 1868) and A Book of Scotish Pasquils. 1568 - 1715 (Edinburgh, 1868). Maidment's stories filled two issues of the Tales.

James Maidment (1794, London - 1879, Edinburgh) was called to the Scottish bar, following his education at Edinburgh University. He became the chief authority on Scottish genealogical cases. Maidment was also a keen amateur collector of Scottish folksong and folklore. He published a number of important ballad collections, including A New Book of Old Ballads (Edinburgh, 1844), Scotish Ballads and Songs (Edinburgh, Glasgow & London. 1859), Scotish Ballads and Songs, Historical and Traditionary 2 vols. (Edinburgh, 1868) and A Book of Scotish Pasquils. 1568 - 1715 (Edinburgh, 1868). Maidment's stories filled two issues of the Tales.

Theodore Martin (September 16, 1816 - August 18, 1909) was born in Edinburgh and obtained his LLD at Edinburgh University. He remained in Edinburgh, where he practised as a solicitor, until moving to London in 1846 where he continued to work in the legal profession. As a young man he began to contribute article to various magazines, using the alias 'Bon Gaultier'. In 1854 he produced a volume of Bon Gaultier Ballads and then proceeded to make his living as a writer. His Life of the Prince Consort (1874 - 80) earned him a knighthood in 1882. Towards the end of his life he was made Rector of St. Andrews University. Like James Maidment, his contributions to the Tales filled two issues.

Other Contributors to the Tales:

Nine tales are from anonymous authors. There is nothing to suggest whether or not these stories are from the same person.

Alexander Bethune and John Bethune

Alexander and John Bethune were brothers, the sons of an agricultural worker, and were born at Upper Ronkeillour in the parish of Monimall, Fife. Alexander was born in 1804 and John in 1812. Alexander began working in the fields when he was nine years old, while John later became an apprentice weaver at Collessie. In 1825 John set up a loom in his home at Lochend, near the Loch of Lindores, and took Alexander on as an apprentice. However, the scheme did not succeed and both brothers returned to the fields, earning a shilling a day. Shortly afterwards Alexander began working in a quarry, but was seriously injured in an explosion in 1829. Three years later he was injured again and remained a cripple for the rest of his life. In spite of their complete lack of education and the hardships of their lives, the brothers wrote prolifically and by 1831 John had made a reputation for himself as a writer.  In 1838 Alexander wrote Tales and Sketches of Scottish Peasantry. John died in 1839, aged only 27 years. After his brother's death, Alexander published John's poems, and a biographical sketch of his life. The book was a success and Alexander was offered the editorship of the Dunfries Standard. But, he too had become frail and he died four years after his brother in 1843.

In 1838 Alexander wrote Tales and Sketches of Scottish Peasantry. John died in 1839, aged only 27 years. After his brother's death, Alexander published John's poems, and a biographical sketch of his life. The book was a success and Alexander was offered the editorship of the Dunfries Standard. But, he too had become frail and he died four years after his brother in 1843.

Matthew Forster Conolly

Matthew Forster Conolly was a solicitor who became Town Clerk of Anstruther, Fife.

Professor Thomas Gillespie c.1843/44

The Reverend Professor Thomas Gillespie DD (1777 - September 11, 1844) was born in the Parish of Closeburn, Dumfries-shire. He studied Divinity at Edinburgh University and became a preacher in Fife. He later became professor of Humanity at St. Andrews University.

Alexander Campbell

It would be tempting to suggest that these stories were from the pen of the writer and musician Alexander Campbell (1764 - 1824), who tried, apparently unsuccessfully, to teach music to a young Walter Scott (1771 - 1832). Campbell is best known for his two volume set of Highland songs and poems Albyn's Anthology (1816). However, as Alexander Leighton appears to suggest that the Alexander Campbell who contributed to the Tales was alive in 1857, we must assume that this person was not the same Alexander Campbell who composed the Albyn's Anthology.

William Hetherington, D.D.

Possibly William Maxwell Hetherington DD LL.B who wrote and edited a number of theological works.

John Howell

John Howell (1788 - 1863) lived in Edinburgh all his life. He had various occupations, including shop assistant (c.1810 - 15), bookbinder (1819 - 25), and dealer in antiquities and/or “polyartist” (1827 - 34). Howell produced a number of books, including An Essay on the War Galleys of the Ancients (Edinburgh. 1829), The Life and Adventures of Alexander Selkirk (Edinburgh. 1829) and The Life of Alexander Alexander (Edinburgh. 1830). Howell was also an 'inventor', although some of his ideas (including an attempt to fly, and his mechanically aided machine for walking on water) came to nothing. According to one friend, Howell was “a person who seemed to know a little of everything, yet failed in most of his inventions”. (It could be that the semi-anonymous 'J.H', who contributed one tale, could also be John Howell.)

Patrick Maxwell

Maxwell is probably identical to a person of that name who contributed to the following work: The Poetical Works of Miss Susanna Blamire “The Muse of Cumbria” Collected by Henry Lonsdale M.D. with a Preface, memoir and notes by Patrick Maxwell. Edinburgh. John Menzies. 1842.

Hugh Miller

Although best known as a geologist and expert on the Old Red Sandstone, Hugh Miller (1802, Cromarty - 1856, Portobello) was also one of Scotland's earliest folklorists. His book Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland (1835, expanded 1850) is still in print today. His death, by his own hand, was brought about by over-work.

Alexander Peterkin

There are a number of people with this name who could possibly be considered as the author of this one tale. For example, there was a bookseller called Alexander Peterkin who lived in Huntingdon and who was painted in 1830 by T Arowsmith. However, it seems more likely to have been an Alexander Peterkin who died in 1846. This Peterkin was a native of Macduff, Banffshire, where his father was parish minister. Peterkin attended Edinburgh University and qualified as a solicitor in 1811. As he was once Sheriff-Substitute of Orkney he was probably the author of the book Notes on Orkney and Zetland that appeared in 1822. Apparently Peterkin spent much of his life 'journalising'. He edited an edition of Robert Ferguson's Poems (1807) and issued a reprint of the Currie edition of Burns' works, to which he added a new preface (1815). He may also have been responsible for editing a work on Scottish church history, Covenanted General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (1838).

Oliver Richardson

I am unable to identify Richardson.

J F Smith

Smith is mentioned as a contributor by James Tait. It seems likely that he is identical to the writer of that name who contributed 'penny dreadfuls' to the London Journal and Weekly Record during the period 1848 - 1873. One story, The Chronicles of Stanfield Hall was based on the true 1848 murder of Isaac Jeremy by James Bloomfield Rush.

Rev G Thomson

I am unable to identify Thomson.

Notes:

1. Wilson's Tales of the Borders. Selected and edited, with biographical notice of the contributors, by James Tait. Edinburgh. Joseph Irving. 1881. p.xi - xii.

2. From To Readers, in Tales of the Borders, number 48. This flowery notification of Wilson's death begins: 'It is our painful duty to send around the land the tidings of the lamented death of Mr JOHN MACKAY WILSON, the Author of these Tales. This event has come upon us at an hour when, in truth, 'we looked not for it'. That grim messenger, whose afflicting visits he has so often affectingly described, has borne his irresistible demand upon him - thrown the gloom of desolation over the bright scene that was expanding before his eyes - and left, in darkness and in sorrow, his bereaved and afflicted friends.'