(l) A step in the Basse Danse, in which the body was swayed from side to side (branlé).

(2) A round dance in duple measure, which was very popular in France in the 16th century. The music of many Branles, and other old dances, is given in Arbeau's Orchésographie (Langres, 1588), a copy of which is in the British Museum.

(3) A French dance popular in England during the 16th century. Its figure is now doubtful, but it has been stated to have been a 'ring' or a 'round' dance in which the dancers join hands as round a maypole. It is identical with the Bransle or Brangill, and probably also with the Brawl, supposed to be so named from its similitude to an altercation. Shakespeare plays upon the word in a dance sense in Love's Labour Lost, Act iii. Scene 1. A description of the measure is given in Morley's Plaine and Easaie Introd., 1597, p. 181.

That the Brangill was a round dance may be inferred from the fact that The Brangill of Poictu from the Skene MS, is the tune of We be Three Poor Mariners, a song in which the sentence occurs: 'Shall we go dance the round, the round'

It is also curious that a traditional remembrance of these words is sung to a round dance by street children to-day.

Ça Ira

The earliest of French revolutionary songs, probably first heard on Oct 6, 1789. when the Parisians marched to Versailles. The words were suggested to a street-singer called Ladré by General La Fayette, who remembered Franklin's favourite saying at each stage of the American insurrection. The burden of the song was then as follows:

Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira!At a later period the burden, though more ferocious, was hardly more metrical:

Le peuple en ce jour sans cesse repète

Ah! ça ire, ça ira, ça ira!

Malgré les mutins, tout réussira.

Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira!The tune - the length and compass of which show that it was not composed for the song - was the production of a certain Bécour or Bécourt, a side-drum player at the Opera, and as a contre-danse was originally very popular under the title of Carillon National.

Les aristocrat' à la lanterns

Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira!

Les aristocrat' on les pendra.

The tune quickly became popular in England and many copies are found in sheet music and in collections of airs. One sheet, published by A. Bland, gives it with the French words as: 'Ah Ça Ira Dictum Populaire ou Carrillon National Chanté a Paris a La Fédération de 14 Juillet 1790'. This and other copies have a strain following on, and additional to the one printed above. The melody was employed in an opera entitled The Picture of Paris, arranged by Shield and produced at Covent Garden on Dec 20, 1790. For many years afterwards, under the name The Downfall of Paris, or The Fall of Paris, it was used for a pianoforte piece with many variations.

Campbells are Coming

This fine and popular air has been the subject of many conflicting legendary statements, the most likely

of which is that it became the gathering tune of the clan Campbell during the Scots Rebellion of 1715. Other accounts give an Irish origin, and one that it was used for a song, composed on and at the period of Mary Queen of Scots' imprisonment in Loch Leven Castle. However this may be the tune cannot be traced either in manuscript or print before 1745, about which year it was used for country dancing under the title Hob or Nob. With this name the air is found in the fourth book of Walsh's Caledonian Country Dances (c. 1745), in Johnson's Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, 1748 and in other contemporary dance books.

Under the heading The Campbells are Coming the melody occurs in Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion (c. 1750), and a few years later in Bremner's Scots Reels. The words with the air are in Johnson's Scots Musical Museum, vol. iii. 1790.

Country Dance

A dance popular in England from an early time to a comparatively recent period, when it was gradually displaced by the introduction of the quadrille, waltz and polka.

The supposition that the dance is of French origin and that its title is merely a corruption of contre-danse or contra-danse (so named from the dancers being ranged opposite each other at the commencement of the figure) has been sufficiently exploded. There can now be but little doubt that the name 'country dance' correctly expresses what the dance really was when introduced into more refined society from the village green, the barn, or the country alehouse. Record of the English 'country dance' so named exists long before any reference to the pastime as popular on the Continent.

Much allusion to the dancing of country dances and the names of them is found in 16th and 17th century literature, and the traditional melodies employed for the dances were used by such musicians as William Byrd and his contemporaries for elaboration into virginal pieces - Sellinger's Round is one of these. Trenchmore, Paul's Steeple, Half Hannikin, Greensleeves, John Come Kiss Me Now and others are melodies which employed the feet of Elizabethan dancers, and all, either as ballad airs or as dance tunes to which ballads were sung, appear to have had birth with the rustic and untutored musician. One peculiarity of the country dance, which has few parallels in other dances, is that it was not confined to any special figure or step and its music was never limited by any special time-beat or accent. As the dance grew in favour in the ballroom and during various periods, the figures appear to have varied somewhat, and there seems to have been a good deal more regularity in them. After the 17th century the early round form of the dance became obsolete, only the long form being in favour. The 17th century figures of the country dance contained many eccentric movements. In The Cobbler's Jigg, for instance, some of the performers are directed to 'act the cobbler' and in Mall Peatly the new way, you are to 'hit your right elbows together and then your left, and turn with your left hands behind and your right hands before, and turn twice round, and then your left elbows together, and turn as before, and so to the next.' The present writer remembers to have seen traditional survivals of these old country dances performed in a cottage on the remote Yorkshire moors, and in these such embellishments occurred.

The first collection of country dances was English, and was issued by John Playford, bearing the date 1651, but really printed at the latter end of the preceding year. This work, entitled The English Dancing Master, contains over a hundred tunes, without bass or even barring, having the dancing directions under each. Country dancing had sufficiently grown into favour even in Puritan times to demand a scientific work on the subject. Playford's Dancing Master forms a record of English melody invaluable to the student of the subject, and the history of our national ballad and song airs is so dependent on it that were the work non-existent, we should have no record of many of our once famous tunes. It is in this respect fortunate that country dances were so elastic as to permit the use of almost any air. The Dancing Master ran through eighteen editions, ranging in date down to 1728, each edition varying and getting larger, even in the later ones extending to two and three volumes. Following Playford's publication music publishers with scarcely a single exception issued yearly sets of country dances generally in books of twenty four, which were frequently reprinted into volumes containing two hundred. They are nearly all in a small, long, oblong shape for the convenience of dancing masters' pockets - the kit being in one and the dance book in the other. This now obsolete type of country dance book expired about 1830, but the form was preserved in the present writer's Old English Dances (Reeves, 1890), in which an attempt is made towards a bibliography of dance collections. The early dance-books are rare and much sought after.

The music for the original country dances of the villages was supplied by a bagpipe, a fiddle or very frequently by the pipe and tabor, a pair of instruments much used for the Morris dance, but from the frontispieces to the 18th century dance books, which generally depicted a country dance in progress, we can see that in the ball-room a more extended orchestra was in vogue. Some of the pictures show the performance of a bass viol, two violins, and a hautboy and in one instance there is a harpsichord in addition.

Besides the dance collections which gave both tunes and figures there were many elaborate treatises on the dance, and its complicated figures certainly demanded some trustworthy guide.

John Weaver wrote several works on the subject, one dated 1720, and Thomas Wilson, a dancing master, a century later was the author of The Complete System of English Country Dancing (c. 1820) and other works in which this kind of dancing is attentively dealt with. As before stated, the quadrille, waltz, and polka quickly ousted the country dance, and a mere relic of it exists or did exist in old-fashioned circles where Sir Roger de Coverley finishes up the evening. It is perhaps worthy of notice that the country dance never obtained any great degree of favour in Scotland, though, danced at the Edinburgh and other fashionable assemblies, the native reel has always held ground against newly introduced dances.

The strange titles found to country dances are due to the circumstance that where the airs are not those of songs or ballads, the composer or dancing masters named them from passing events, persons prominently before the public, patrons of assemblies, etc. The Rebell's Flight, Jenny Cameron (1745-4), Miss M'Donald's Delight, Woodstock Park, etc., are examples. The giving of fresh life to old tunes by new names was of course frequent.

The airs below are types of country dance tunes at different dates:

Sir Hubert Parry, and Professor (now Sir C. V.) Stanford, were Vice-Presidents. The original committee consisted of Mrs. Frederick Beer, Miss Lucy E. Broadwood, Sir Ernest Clarke, Mr. W. H. Gill, Mrs. L. Gomme, Messrs. A. P. Graves, E. F. Jacques, Frank Kidson, J. A. Fuller Maitland, J. P. Rogers, W. Barclay Squire, and Dr. Todhunter. Mrs. Kate Lee was Hon. Secretary and Mr. A. Kalisch Hon. Treasurer. During the first year 110 members were enrolled. There have been five publications issued (up to June 1904), and much useful work done in attracting attention to the necessity of noting down our folk-songs before they are entirely lost. In 1904 Miss Lucy E. Broadwood became Hon. Secretary, and Lord Tennyson, President.

Since its establishment in 1898 the Folk-Song Society has grown into great prominence, and much earnest work has been done. Up to December 1909 thirteen 'Journals ' have been published, each usually of greater bulk than its predecessor. The southern counties of England have been especially well ransacked for traditional song by members and the best of the gleaning forms the contents of the Journals. Norfolk and Lincolnshire and Ireland have also contributed many interesting melodies, and some hitherto unknown carols have been noted down. In some instances the phonograph has been employed in recording tunes. An important collection of Gaelic folk music is to form the next issue of the Society. Mrs Walter Ford became Hon Secretary in 1909 and there are over 200 members.

The success of the English Folk-Song Society has induced the formation of similar bodies in Ireland and in Wales. The Irish Folk-Song Society was established May 1904, and several journals have appeared. The Welsh Folk-Song Society had its real formation in a meeting held at Llangollen, Sept 2, 1908, though a prior meeting, held during the National Eisteddfod of 1906, led the way. One journal has been published and another is in the press.

In Scotland there are several societies which make the collection of folk-music and folk-rhyme part of their programme. The Rymour Club, Edinburgh, is one of these, and the Buchan Club has devoted at least one of its 'Transactions' to the subject of 'Folk Song in Buchan'.

Gittern (or Ghittern, etc.)

An obsolete instrument of the guitar type. It is mentioned several times by Chaucer in such terms as to show that it was used for the accompaniment of songs. Other later writers refer to it, and it is named in a list of musical instruments which had belonged to Henry VIII. as: 'Four gitterons which are called Spanish vialles'. There can be but little doubt that it underwent many minor changes in shape and character during the period of its use, and that the name was by no means definitely fixed upon one particular form, but would be assigned to any of the guitar tribe.

In the 17th century it appears to have had but little difference from the cithren, that difference being its smaller size, and its being strung with gut instead of wire, as was the cithren. Drayton in Polyolbion, 1613, seems to confirm this as to stringing by the lines:

Some that delight to touch the sterner wireIn An English Dictionary by E. Coles, 1713 the definition of ghittern is 'a small kind of cittern'. John Playford published, with the date 1652, A Book of New Lessons for the Cithren and Gittern, a copy of which is in the Euing Library, Glasgow. In advertisements Playford alludes to this (a later edition) as having been 'printed in 1659', and at various dates between 1664 and 1672 he advertises as 'newly printed' another work, Musick's Solace on the Cithren and Gittern. The gittern and cithren never appear to have had much popularity in England, and after the last-named date they seem to have died a natural death. The music transcribed for the instruments was written in tablature on a four-line stave. About 1756-58 the cithren had a revival in the English guitar, a wirestrung instrument which closely resembled it. This, however, gave place to the gut-strung Spanish variety as now used. (See Cither, Guitar.)

The Cithren, the Pandore and the Theorbo strike.

The Gittern and the Kit the wandering fiddlers like.

Another bagpipe firm founded by Alexander Glen (born at Inverkeithing in 1801), elder brother of the preceding Thomas Macbean Glen, is established in Edinburgh. Both firms have issued musical works in connection with the bagpipe.

John Glen, son of Thomas Macbean Glen born in Edinburgh in 1833, was a high authority on, and possessed a uniquely valuable library of, early Scottish music. His published works are: The Glen Collection of Scottish Dance Music, two books, 1891 and 1895, and Early Scottish Melodies, 1900. All these are full of original research, and contain much biographical and historical matter which the student cannot afford to ignore. He died Nov. 29, 1904.

Robert Glen, his younger brother, born in Edinburgh 1835, is an equally great authority on ancient musical instruments, of which he has a fine collection, and on Scottish antiquities. He is, in addition, an accomplished artist in the representation of old instruments and similar subjects.

Gow

A family of Scottish musicians notable during the latter part of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, the first of whom -

Niel Gow's portrait was painted by Sir Henry Raeburn, and was reproduced in a mezzotint plate. It is curious to note that the chin is placed on the right side of the tailpiece, showing that Gow retained the habit of the old violinists, first altered by Geminiani.

Nathaniel Gow

... the most famous of Niel Gow's sons, was born at Inver, May 28, 1763. In early life he came to Edinburgh, and at the age of sixteen was appointed one of His Majesty's Trumpeters for Scotland at a salary of £70 or £80 per year. In Edinburgh he took lessons on the violin from the best Scottish violinists, to supplement those given him by his father. In 1791 he succeeded his brother, William, as leader of the orchestra of the Edinburgh Assembly, and throughout the rest of his life maintained a high position in the Scottish musical world as performer, provider, and composer of the dance-music then in use in the northern capital. Whether or not his playing was equal to that of his father, it is certain that he was a more tutored performer, and had, in addition, some skill in composition and theoretical music. In 1796 he entered as partner in a musio-selling and publishing business with William Shepherd, an Edinburgh musician and composer, their first place of business being at 41 North Bridge Street, Edinburgh. Nathaniel Gow had, before this, aided his father in the issue (through Corri and Sutherland) of three collections of Strathspey reels. While Gow was still actively engaged in his ordinary professional work the firm Gow and Shepherd published vast quantities of sheet music (principally dance-music), and numbers of 'Collections' by the Gow family and others. In or about 1802 Gow and Shepherd removed to 16 Princes Street (which, in 1811, was renumbered 40), and did even a larger business than before. Shepherd having died in 18l2 Gow found himself in monetary difficulties, and unable to meet his partnership liabilities with his partner's executors, in spite of the great trade done by the firm and Gow's professional earnings, which were exceptionally large. In 1814 the stock-in-trade was sold off but in 1818 Gow again entered into the music business, with his son Niel Gow, as a partner at 60 Princes Street. This continued until 1893, when the son died. For eight months Gow was again a partner in the musie trade with one Galbraith, but Gow and Galbraith ceased business in 1827, when Glow became bankrupt. About this time he also was attacked with a serious illness, which confined him to his room until his death on Jan 19, 1831. In his later years his patrons were not backward in his behalf. A ball for his benefit realised £300, and other three in subsequent years yielded almost as great a sum. He had a pension from George IV and another of £50 a year from the Caledonian Hunt. He was twice married, and left a family behind him, not distinguished as musicians; his clever son, Niel, died before his father. For particulars regarding the Gow family the reader is referred to John Glen's Scottish Dance Music, bk. ii. 1895 - and for a contemporary notice to the Georgian Era, vol. iv. 1834. A biographical article on Niel Gow appeared in The Scots' Magazine for January 1809.

The chief composition by which Nathaniel Gow is remembered to-day is Caller Herrin, a piece written as one of a series to illustrate the musical street-crices of Edinburgh. The original sheet, which was published about 1798 or 1800 gives the cry of the Newhaven fishwife mingling with 'George St. bells at Practice' and other fishwives entering into the scene. This remained purely as an instrumental tune for more than twenty years, when Lady Nairne, taking the melody, wrote her best lyric to it and published them together in The Scotish Minstrel, vol. v. (c. 1823).

After Gow's bankruptcy Alexander Robertson and Robert Purdie, both Edinburgh music publishers, acquired the rights of publication of the Gow Collectious, and added to them The Beauties of Niel Gow (three parts), The Vocal Melodies of Scotland (three parts), and The Ancient Curious Collection of Scotland one part. As the Gow 'Collections' are of the highest value in the illustration of Scottish National music (many of the airs contained therein being traditional melodies printed for the first time) the following list with the dates of publication is given:

Other sons of Niel Gow were William (1751-1791), Andrew (1760-1803), and John (1764, Nov. 22, 1826). They were each musicians of average merit as violinists and composers of Strathspeys, etc., some of which appear in the Gow publications.

Prior to 1788 John and Andrew had settled in London, where they established a music selling and publishing business at 60 King Street, Golden Square. On the death of Andrew in 1803 John removed to 31 Carnaby Street, Golden Square, and in 1815-16 to 30 Great Marlborough Street. Before 1824 he had taken his son into partnership, and at 162 Regent Street they were 'music-sellers to His Majesty', issuing much of the then popular quadrille and other sheet dance-music.

Stainer and Barrett in their Dictionary of Musical Terms suggest that 'hornpipe' has been originally 'cornpipe' named from a pipe of straw, and mentioned by Shakespeare in the line, 'When shepherds pipe on oaten straws', but the present writer would rather refer it to its more obvious original, a pipe made from a horn.

As a dance the hornpipe was well known in this country in the 16th century. There is a 'Hornepype' by Hugh Aston (temp. Hen. VIII. ) in the Brit. Mus. MSS. Reg. Appendix 58, a portion of which is printed in Wooldridge's edition of Chappell's Popular Music. Barnaby Rich, writing in 1581, mentions its popularity, and Ben Jonson in the Sad Shepherd speaks of it as 'the nimble hornpipe'. Among the country people of Lancashire and Derbyshire the hornpipe was much cultivated, and for a long time after its disappearance in other parts, these counties were famous for it.

Hawkins names one John Ravenscroft, a Wait of the Tower Hamlets, who was especially noted for the playing and composition of hornpipes; he prints a couple of these (in date about 1700) in his History. All these early hornpipes are in triple time, and the method of dancing them is now unknown. As many are included in collections of country dances some would be danced as these are, but there is a probability that they were also, like the modern hornpipes danced by a single performer to either a bagpipe or a violin. Though there are several books of hornpipes mentioned in the advertisements of early 18th century music books yet very few collections have survived in our libraries. One of the books of hornpipes so advertised (in Keller's Thorough Bass published by John Cullen in 1707) is called 'A Collection of original Lancashire Hornpipes old and new ... being the first of this kind published. Collected by Thomas Marsden, price 6d.'

The following (right) is a fairly typical example of an early triple time hornpipe; it is found in several books of country dances issued about 1735 as - Wright's Collection of 200 Country Dances, vol. i., and one of Walsh's Compleat Country Dancing Master, etc.

Earlier specimens may be seen under the titles Ravenscroft's Hornpipe and Bullock's Hornpipe, in the third volume of The Dancing Master (Pearson and Young) - circa 1726.

About 1760 the hornpipe underwent a radical change, for it was turned into common time and was altered in character. Miss Anne Catley, Mrs. Baker, Nancy Dawson, and other stage dancers, introduced it into the theatre, and they have given their names to hornpipes which are even now popular.

Dr. Arne included a couple of common time hornpipes into his version of King Arthur, 1770.

Dr. Arne included a couple of common time hornpipes into his version of King Arthur, 1770.

A specimen of the late hornpipe (circa 1798) is here given (left). It is named after one Richer, a rope and circus dancer of some celebrity in his day.

The stage hornpipe was generally danced between the acts or scenes of a play even as late as 1840 or 1850.

The hornpipe's association with sailors is probably due to its requiring no partners, and occupying but little dancing space - qualities essential on shipboard.

The latest modern development of the hornpipe is to break up the regular time and even notes of the old common time ones by making the bars up of dotted quavers and semiquavers, producing a sort of 'Scotch snap.'

Handel ends the seventh of his 12 Grand Concertos with one which may serve as a specimen of the hornpipe artistically treated. In his Semele the chorus, 'Now Love, that everlasting boy', is headed alla hornpipe.

Hurdy Gurdy

After a long introduction and description of the instrument and its music by A J Hipkins, Kidson adds:

By some strange misconception, a common example of the erroneous nomenclature which exists among average non-musical persons regarding the lesser-known instruments, it has long been the practice, both in literature and in speech, to refer to the barrel and piano organs as 'hurdy gurdies'. This has probably arisen from the fact that the Italian street-boys, who in the twenties and thirties perambulated town streets with this instrument, in due course discarded it for a primitive form of organ which simulated the then popular cabinet piano. Out of this the modern piano organ has evolved.

Irish Music - Bibliography

Since the above (the Irish Music entry) was written for the first edition of the Dictionary, the study of Irish Music has gone on in a more systematic manner, with the result that fresh light has been thrown on certain points. The following extended and corrected bibliography of the fountain-heads of Irish traditional music will, it is believed, be found fuller than any before published:

The above list represents, it is believed, a very comprehensive bibliography of books, wherein traditional Irish music appears for the first time in print, some of the works having a greater number of hitherto unpublished airs than others. The numerous 'Collections', old and new, made up of airs published in other places are excluded. Works bearing on the history of Irish music not included in this list are Hardiman's Irish Minstrelsy, 2 vols. 1831, Conran's National Music of Ireland, 1850, and some others. Mr. W. E. Grattan Flood has lately (1905) completed a History of Irish Music.

Jorram

A Highland boat-song, sung to accompany and give time to the pull of the oars in a rowing boat. The two here given, taken from the Rev. Patrick Donald's excellent Collection of Highland Vocal airs never hitherto published, 1783, are noteworthy as traditional melodies current for this purpose in Perthshire and in Skye respectively. It is interesting to compare these with the Italian barcaroles and the boat-songs of other nations.

Lament

In Scottish and Irish folk music are melodies named as 'Laments' or 'Lamentstions'. In Scottish music these were mainly confined to the Highlands, and were generally purely bagpipe tunes, consisting of an air, sometimes set vocally, with a number of more or less irregular variations or additional passages. Each of the clans or important families had its particular lament, as well as its 'gathering', and the former was played on occasions of death or calamity. Many of the laments are of wild and pathetic beauty: McGregor a ruaro and Mackrimmon's Lament are among those which have become more widely familiar.

The latter, Sir Walter Scott says, 'is but too well known from its being the strain wllieh the emigrants from the West Highlands and Isles usually take leave of their native shore'. The burden of the original Gaelic words is 'we return no more'. Of the same class is Lochaber No More (q.v.) which is a true 'Lament to the Highlander'. The melody in one of its earlier forms is entitled 'Lamentation' or 'Irish Lamentation', and there seems to be but little doubt that the song has been written to an air then generally recognised as a Lamentation. For examples of the Gaelic laments the reader is referred to Patrick McDonald's Highland Vocal Airs, 1783; Albyn's Anthology, 1816-18; and other collections of Highland airs.

Bunting supplies several current in Ireland, and in Aria di Camera, c. 1727, are some of the earliest in print, viz. Limerick's, Irish, Scotch, Lord Galloway's and MacDonagh's

Lamentations.

Luinig, or Luineag

A choral song used to accompany labour, sung (or formerly sung) principally by women in the remote Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Patrick M'Donald, 1783, says that they were of a plaintive character, and were then most common on the north-west coast of Scotland and in the Hebrides. He mentions that Luinigs were 'sung by the women not only at their diversions but also during almost every kind of work where more than one person is employed, as milking cows, fulling cloth, grinding of grain', etc. When the same airs were sung as a relaxation the time was marked by the motions of a napkin held by all the performers. One person led, but at a certain passage he stopped, and the rest took up and completed the air. As they with were sung to practically extemporary words by the leader with a general chorus, they resembled the sailors Chanty of modern times. A 'Luineag' is given in Albyn's Anthology, 1818, vol. ii.

McDonald, Malcolm

A Scottish composer of Strathspeys of some note during the latter part of the 18th century. Little is known of his personal history save that he was associated with the Glow family, and that he lived (and probably died) at Inver, the birthplace of Niel Glow. A footnote in The Beauties of Niel Gow states that he played the violoncello in Gow's band at Edinburgh. His published collections of Strathspey reels number four. The first in oblong folio was published in 1788; 2nd in folio, c. 1789; 3rd folio, c. 1792; a 4th folio, c. 1797.

The marimba is also known in Africa, where it is formed in a similar, but rather more primitive fashion, gourds taking the place of the wooden sound-boxes.

Monferrina

A kind of country dance, originating in Piedmont. The tunes used in Italy and Malta became fashionable in England in the early years of the 19th century, and were employed for country dances. In this country the name stood as 'Monfrina, Monfreda or Manfredina.

A kind of country dance, originating in Piedmont. The tunes used in Italy and Malta became fashionable in England in the early years of the 19th century, and were employed for country dances. In this country the name stood as 'Monfrina, Monfreda or Manfredina.

The favourite tune with the title 'Italian Monfrina' was as shown. Copies will be found in Wheatstone's Country Dances for 1810, Companion to the Ball-Room c. 1816, and other collections of country dances.

Morris, or Morrice, Dance

A sort of pageant, accompanied with dancing, probably derived from the Morisco, a Moorish dance formerly popular in Spain and France. Although the name points to this derivation, there is some doubt whether the Morris Dance does not owe its origin to the Matacins. In accounts of the Morisco, no mention is made of any sword-dance, which was a distinguishing feature of the Matacins, and survived into the English Morris Dance (in a somewhat different form) so late as the 19th century.

Jehan Tabourot, in the Orchésographie (Langres, 1588), says that when he was young the Morisco used to be frequently danced by boys who had their faces blacked, and wore bells on their legs.  The dance contained much stamping and knocking of heels, and on this account Tabourot says that it was discontinued, as it was found to give the dancers gout. The tune to which it was danced is shown.

The dance contained much stamping and knocking of heels, and on this account Tabourot says that it was discontinued, as it was found to give the dancers gout. The tune to which it was danced is shown.

The English Morris Dance is said to have been introduced from Spain by John of Gaunt in the reign of Edward III, but this is extremely doubtful, as there are searcely any traces of it before the time of Henry VII, when it first began to be popular. Its performance was not confined to any particular time of the year, though it generally formed part of the May games. When this was the ease, the characters who took part in it consisted of a Lady of the May, a Fool, a Piper, and two or more dancers. From its association with the May games, the Morris Dance became incorporated with some pageant commemorating Robin Hood, and charaters representing that renowned outlaw, Friar Tuck, Little John, and Maid Marian (performed by a boy), are often found taking part in it. A hobby-horse, four whifflers, or marshals, a dragon, and other characters were also frequently added to the above. The dresses of the dancers were ornamented round the ankles, knees, and wrists with different-sized bells, which were distinguished as the fore bells, second bells treble, mean, tenor, bass, and double bells. In a note to Sir Walter Scott's Fair Maid of Perth there is an interesting account of one of these dresses, which was preserved by the Glover Corporation of Perth. This dress was ornamented with 250 bells, fastened on pieces of leather in twenty-one sets of twelve, and tuned to regular musical intervals.

The Morris Dance gained its greatest popularity in the reign of Henry VIII, thenceforward it degenerated into a disorderly revel, until, together with May Games and other 'enticements unto flightiness', it was suppressed by the Puritans.  It was revived at the Restoration, but the pageant seems never to have attained its former popularity, although the dance continued to be an ordinary feature of village entertainments 'til within the memory of persons now living.

It was revived at the Restoration, but the pageant seems never to have attained its former popularity, although the dance continued to be an ordinary feature of village entertainments 'til within the memory of persons now living.

In Yorkshire the dancers wore peculiar head-dresses made of laths covered with ribbons, and were remarkable for their skill in dancing the sword dance over two swords placed crosswise on the ground. A country dance which goes by the name of the Morris Dance is still frently danced in the north of England. It is danced by an indefinite number of couples, standing opposite to one another, as in Sir Roger de Coverley. Each couple holds a ribbon between them, under which the dancers pass in the course of the dance. In Cheshire the tune (shown above, left) is played for the Morris dance.

In Yorkshire the following tune, founded on that of The Literary Dustman, is generally used (right).

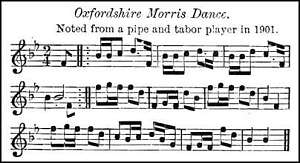

More or less modernised forms of the Morris dance still linger in certain country places, both in the north, and in the south of England.  In Oxfordshire there are Morris dancers who perform to the music of a pipe and tabor. The following tune (left) was noted down by the present writer from a pipe and tabor player, as one used for the Morris dance in an Oxfordshire village.

In Oxfordshire there are Morris dancers who perform to the music of a pipe and tabor. The following tune (left) was noted down by the present writer from a pipe and tabor player, as one used for the Morris dance in an Oxfordshire village.

In Yorkshire, and in Northumberland, the sword - dance is a feature of the Morris and in the Whitby and other districts of north Yorkshire the pastime is called 'plew stotting'. 'Plew' is the local pronunciation of plough, and 'stot' is a young bull; formerly yoked to the plough. The 'plew stots' are bands of youths (one dressed as the 'maiden ' - no doubt a survival of Maid Marian - and another as the 'old man') who parade from village to village dancing the sword dance and other dances, to the accompaniment of a fiddle. In Traditional Tunes, 1891, edited by the present writer, is a Lancashire Morris dance, danced at 'rush bearings' in that country. It is noticeable that most Morris dances are in either common, or 2 - 4 time, and the Helston Furry Dance, which is a true Morris dance, is a very characteristic example. Of a different type is the following, which we may assume to be a traditional Welsh Morris in a book of country dances issued by John Walsh about 1730-35, it is there entitled Welsh Morris Dance.

Negro Music of the U.S.

(Part 3 of entry)

Prior to about 1835 English people had neither knowledge of, nor interest in, the folk-music of the American negro. Some few examples, though probably not many more than half a dozen, had appeared in print before that time,  and one characteristic specimen from Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish, and Foreign Airs, vol. i. [1782], is appended. It has the incessant repetition of phrase found in so many negro airs. One or two others from Virginia are in the same work. The words of these Plantation melodies seem to have been merely a string of sentences concocted on the spur of the moment by the singer as he performed the 'Walk Round' (much the same sort of thing as the 'Cake Walk' of to-day), while a steady clapping of hands from the spectators marked the time.

and one characteristic specimen from Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish, and Foreign Airs, vol. i. [1782], is appended. It has the incessant repetition of phrase found in so many negro airs. One or two others from Virginia are in the same work. The words of these Plantation melodies seem to have been merely a string of sentences concocted on the spur of the moment by the singer as he performed the 'Walk Round' (much the same sort of thing as the 'Cake Walk' of to-day), while a steady clapping of hands from the spectators marked the time.

As to the African origin of these tunes many theories have been offered, from the belief in their practical genuineness as real native strains (a view apparently supported in the previous section of this article), down to the contemptuous attitude of some who take them to have been manufactured in deliberate imitation of European models, by ignorant musicians for the enjoyment of their fellow-slaves. The truth is probably to be found somewhere between these two extremes. We may admit at once that the rhythmic peculiarities noticed above are to be traced to the original home of the African slave; as all students of primitive music know, distinct rhythms are among the most marked characteristics of savage music. As to the scales in which the melodies of the earlier songs are cast, those who have made a scientific study of folksong hesitate to accept any conclusion which confines certain scales to any one country or date; beyond the broad fact that the pentatonic scale is probably the mark of an earlier date than the church modes, while these again are earlier than our modern major and minor scales, there is little or no possibility of defining more closely the geographical source of any melody. There are, for example, perhaps as many British folk-songs in the pentatonic scale as could be found among the traditional music of any other race or nation and any of these may well have I been caught up from the descendants of the first American settlers, and the rhythms gradually changed to suit the congenital taste of the coloured race.

About 1834-35 one Dan Rice introduced the grotesque song and dance of the negro to the audience of American theatres and concert halls. His first song was 'Jim Crow,' the main burden of which with appropriate actions ran:

Every time you wheel about you jump Jim Crow.Though no doubt this was a plantation lyric, there are signs that the melody has been considerably tampered with. Rice, bringing the song to England about 1835-36, the whole nation became in a perfect ferment over it. Coal Black Rose, Sich a Getting Upstairs, Dandy Jim from Carolina, and Jim Along Josey, were others of this early period. The singing of negro songs having become general, bands of 'Ethiopian Serenaders' appeared in the theatres of America and in England the forties. Christy's, the most famous of these, was of a rather later date.

While in the earlier days the entertainments professed to represent the plantation song and dance with banjo, bones, and fiddle accompaniment, this soon gave way to the introduction of other songs of better literary merit than the meaningless jumble of words of the original songs. Stephen Foster (1826-64) supplied such lyrics as Old Folks at Home, etc., and an attempt was made to give some picture life of the slave in the songs sung. The meetings and religious services have also provided negro songs, many of that origin.

After the slavery days the condition of the American negro has greatly changed, and with this his ditties. The modern 'coon' or 'plantation' songs, and the popular form of syncopation - called 'rag-time', are all easily to be traced to their source in the older negro songs, which as hinted above, are probably to be regarded as European in melodic origin, translated into rhythms that have been handed down from the generation of slaves who actually came from Africa.

Noël

A peculiar kind of hymn or canticle of mediæval origin, composed and sung in honour of the Nativity of Our Lord.

The subject of the observance of Christmas by song and music is so wide, and materials so scattered that it is quite impossible to deal with it in an; adequate manner in such a work as the present. In France, carol-singing appears to have had always an important place in Christmas rites, and there are a great number of ancient, as well as of comparatively modern French carols extant. In Scotland the practice of carol-singing practically ceased in the 16th century, and has not yet been resumed. In England it has always been regarded with favour, though year by year the traditional carols are heard less and less.

Christmas carols of an early date are plentifully scattered through the MS preserved in our great libraries, and the British Museum is rich in them.

Besides the religious aspect the carol has also its festive feature, and it is rather difficult to say which of the two predominates in the greater number. The religious carols were, in many cases, taken from the apocryphal New testament.

It is stated that in France Christmas carols were, in the 13th century, hawked about the streets, and from early times it has been customary in England for printers of garlands and ballad sheets to issue annually sets of the popular Christmas carols. The tunes to which such carols as God rest you, merrie Gentlemen and others similar are and were sung; are traditional melodies coming from the same sources as the English folk-song, and the journals of the Folk Song Society and other collections of English folk-melodies contain many interesting examples.

The following bibliography of the principal collections of carols, though barely touching the fringe of the subject, may be of service.

After his death an attempt towards a second volume of his quarto work was made, but only forty-eight pages were printed. Recently the Irish Literary Society of London issued, under the editorship of Sir C. V. Stanford, The Complete Petrie Collection, (Boosey, three parts), which, containing 1582 airs, comprises all the melodies Petrie left behind him in manuscript. It is needless to enlarge on the value of such a collection of airs noted in Ireland, though every one of them cannot be justly claimed as of Irish origin.

Playford, John, the elder

According to the researches into his pedigree made by Miss L M Middleton (Notes abut Queries, and Dict of Nat. Biog.), was a younger son of John Playford of Norwich, and was born in 1623. In 1648 his name appears as bookseller in London, and in November 1650 he published his first musical work, The English Dancing-Master dated 1651. From this time onward his publications were entirely musical. They included Hilton's Catch That Catch Can, Select Musicall Ayres and Dialogues and Musick's Recreation on the Lyra Violl. He was from 1653 clerk to the Temple Church, and held his shop in a dwelling-house connected with the Temple ('in the Inner Temple near the Church door'); as his wife kept a boarding-school for young ladies at Islington, he in due course removed there, still keelping on his place of business in the Temple. His house at Islington was a large one 'near the church' and after his wife's death in 1679 he advertised it for sale (see Smith's Protestant Magazine, April 11 ,1681), removing to Arundel Street 'near the Thames side the lower end and over against the George' (some references give this as 'over against the Blew Ball'). The character of the man appears to have been such as made him liked and respected by all who came into contact with him, and he seems to have well earned his general epithet 'Honest' John Playford. According to the new edition of Pepys' Diary edited by Wheatley, Samuel Pepys had very friendly relations with Playford, the latter frequently giving him copies of his publications.

In music-publishing Playford had no rival, and the list of his publications would practically be a list (with the exception perhaps of less than twenty works) of all the music issued in England during the time covered by his business career. Playford was enough of a musician to compose many psalm tunes and one glee which became popular, Comely Swain, why Sitt'st Thou So; and to write a handbook on the theory of music which, concise, plain, and excellent, might well serve for a model to-day. This Introduction to the Skill of Musick attained nineteen or twenty editions, and was the standard textbook on the subject for nearly a century; the first edition is dated 1654, and the last 1730. In 1656 Playford published an enlarged edition of it, which long passed as the first. See the Sammelbände of the Int. Mus. Ges, vi. 521. It is divided into two books, the first containing the principles of music, with directions for singing and playing the viol; the second the art of composing music in parts, by Dr. Campion, with additions by Christopher Simpson. The book acquired great popularity; in 1730 it reached its nineteenth edition, independent of at least six intermediate unnumbered editions. There are variations both of the text and musical examples, frequently extensive and important, in every edition. In the tenth edition, 1683, Campion's tract was replaced by 'A Brief Introduction to the Art of Descant, or composing Music in parts', without author's name, which in subsequent editions appeared with considerable additions by Henry Purcell. The seventh edition contained, in addition to the other matter, 'The Order of performing the Cathedral Service', which was continued, with a few exceptions, in the later editions. Another of Playford's important works was the Dancing-Master, a collection of airs for the violin used for country dances, the tunes being the popular ballad and other airs of the period. This work ran through a great number of editions from 1650 to 1728 and is the source of much of our National English melody. Courtly Masquing Ayres of two parts (a title-page of the treble part is preserved in the Bagford collection in the British Museum, Harl. MS. 5966) appeared in 1662.

Other valuable works in a series of editions were published by Playford, books of catches, of psalms, and songs. Instruction-books and 'lessons' for the cithern, viol, and flageolet also followed in a number or editions. After Playford's death many of these were continued by his son Henry, and by Wm. Pearson and John Young, who ultimately acquired the rights of publication.

In the early times of his business, Playford was in trade relations, if not in partnership, with others, John Benson, 1652; Zach Walkins, in 1664-65; and later than this with John Carr, who kept a music-shop also in the Temple, a few steps from John Plagrford's.

Many mistaken statements have been made regarding Playford's business. For instance, it is mentioned (Dict. Nat. Biog.) that he invented the 'new ty'd notes' in 1658. This is quite an error. The tied note was not introduced before 1690, some years after Playford's death (see vol. ii. p. 383 ; vol. iii. p. 325). Neither is it true that in 1672 he began engraving on copper.

John Playford, sensors was neither a printer nor an engraver and long before 1672 he had Issued musical works printed from engraved copper plates. In 1667 Playford republished Hilton's Catch that catch can, with extensive additions and the second title of The Musical Companion, and a second part containing 'Dialogues, Glees, Ayres, and Ballads, etc'; and in 1672 issued another edition, with further additions, under the second title only. Some compositions by Playford himself are included in this work. In 1671 he edited Psalms and Hmns in solemn musick of four parts on the Common Tunes to the Psalms in Metre: used in Parish Churches; and in l677, The Whole Book of Psalms, with the ... Tunes ... in three parts, which passed through twenty editions. In 1673 he took part in the Salmon and Lock controversy, by addressing a letter to the former, 'by way of Confutation of his Essay, etc.', which was printed with Lock's Present Practice of Musick Vindicated. The style of writing in this letter contrasts very favourably with the writings of Salmon and Lock. In place of abuse we have quiet argument and clear demonstration of the superiority of the accepted notation. Towards the year 1684 Playford, feeling the effects of age and illness, handed over his business to his son Henry; and there is a farewell to the public, in the fifth book of Choice Ayres and Songs, 1684. All attempts to settle satisfactorily the date of John Playford's death have hitherto failed. The likeliest date is about November 1686 (Dict. Nat. Biog.), and this is borne out by his unsigned will, which, dated Nov. 5, 1686, was not proved until 1694, the handwriting being sworn to, on the issue of probate. It may be supposed that the will was written on his deathbed, and that from feebleness or other cause it remained without signature. That he was dead in 1687 is proved by several elegies; one by Nahum Tate, set to music by Henry Purcell, was issued in folio in this year. Dr. Cummings suggests (Life of Purcell, p. 46) that this relates to John Playford the younger, but he has overlooked the fact that an Elegy 'on the death of Mr. John Playford, author of these, and several other works' appears in the 1687 and later editions of Playford's Introduction to the Skill of Musick, a work incontestably by the elder John Playford.

There are several portraits of the elder Playford extant taken at different periods of his life, and these are Prefixed to various editions of the Introduction.

Port

A term formerly in use in Scotland to denominate a 'Lesson' or more properly a musical composition for an instrument, principally, it appears, the harp. Rory Dall's Port (i.e. Blind Rory or Roderick's composition) is the best-known survival. It was a piece associated with the blind harper above named, in the 17th century, but in more modern times adapted to Burns's song, Ae Fond Kiss and then we Sever.

There are several 'Ports' in the Straloch Lute MS, 1627, including Jean Lindsay's Port; and the 17th-century Skene MS has Port Ballangowne. Tytler, the writer of a famous 18th-century Dissertation on Scotish Music speaks of it as a particular type of composition, and says that 'every great family had its own Port' named after the family.

Preston & Son

A family of London music-publishers during the latter part of the 18th and the early portion of the l9th centuries. The firm was first commenced by John Preston, who in 1774 was established at 9 Banbury Court, Long Acre, as a musical instrument-maker. In 1776 he had removed to 105 Strand, near Beaufort Buildings, and was publishing some small and unimportant musical works. Two years later he was at 97 Strand, where the firm remained until 1823. John Preston's business after his removal to the Strand soon became one of the most important in the trade, and he issued a vast quantity of music of all kinds, buying, in 1789, the whole of the plates and stock-in-trade of Robert Bremner, who had then just died. About this time the son, Thomas, came into the business, and towards the end of the century John's name disappears. In 1823 Thomas Preston had left the Strand for 71 Dean Street, Soho, where he remained until about 1836, the business then becoming the property of Coventry & Hollier, who reissued some of the Preston publications. Shortly after 1860 Messrs. Novello were large purchasers at their sale of effects.

The Preston publications include an interesting series of country dances commenced in 1788, and extending for nearly forty years after this date. Others are many of the popular operas of the day; such works as Bunting's Ancient Music of Ireland, 1796; W. Linley's Shakespeare's Dramatic Songs, J. S. Smith's Musica Antiqua, etc. They were also the London publishers of George Thomson's Scottish, Irish, and Welsh collections.

Ribible

An obsolete instrument played with a bow. It is mentioned by Chaucer and other early writers, and appears to have been either the rebec itself, or a particular form of it.

Sometimes it is spelled 'rubible'. It has be suggested that both 'rebec' and 'ribible' derived from the Moorish word 'rebeb' or 'rebab' which seems to have been the name a somewhat similar musical instrument.

Riddell, John (or 'Riddle')

Composer of Scottish dance music, born at Ayr, Sept 2, 1718. It is stated in The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire, 1846, that Riddell was blind from infancy, also that he was composer of the well known tune Jenny's Bawbee. This latter statement is not authenticated. Burns mentions him as 'a bard-born genius,' and says he is composer of 'this most beautiful tune' - Finlayston House.

Riddell published about 1766 his first Collection of Scots Reels, or Country Dances, and Minuets, and a second edition of it, in oblong folio, in 1782. He died April 5, 1795.

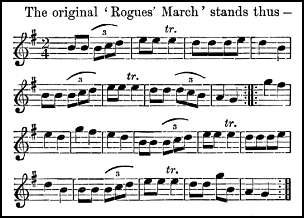

Rogues' March, The

Originally a military quickstep, which for some cause has become appropriate to use when offenders are drummed out of the army. When, from theft, or other crime, it is decided to expel a man from the regiment, the buttons bearing the regimental number, and other special decorations, are cut from his coat, and he is then marched, to the music of drums and fifes playing The Rogues' March,  to the barrack gates, and kicked or thrust out into the street. The ceremony still continues at the present day. The writer, though he has made diligent search, cannot find traces of the tune before the middle of the 18th century, although there can be but little doubt that the air, with its association, had been in use long before that time.

to the barrack gates, and kicked or thrust out into the street. The ceremony still continues at the present day. The writer, though he has made diligent search, cannot find traces of the tune before the middle of the 18th century, although there can be but little doubt that the air, with its association, had been in use long before that time.

About 1790, and later, a certain more vocal setting of the air was used for many popular humorous songs. Robinson Crusoe, Abraham Newland, and the better-known Tight Little Island, are among these. The latter song, as The Island, was written by Thomas Dibdin about 1798, and sung by a singer named Davies at Sadler's Wells in that year.

It is found in many 18th-century collections of fife and flute music the above copy is from The Compleat Tutor for the Fife London. Printed for and sold by Thompson & Son, 8vo, c. 1759-6O.

Root, George Frederick

An American popular composer, born at Sheffield, Mass., U.S.A., August 30, 1820. He studied under Webb of Boston, and afterwards in Paris in 1850. He was a music-publisher in Chicago in 1859-71. He was associated with Lowell Mason in popularising music in American schools, etc., and had a musical doctor's degree conferred on him at the Chicago University. He died at Barley's Island, August 6, 1895.

He wrote various cantatas, such as The Flower Queen, Daniel, and others, but is best known as composer of certain songs much sung during the American Civil War, as, The Battle-Cry of Freedom, Just before the Battle, Mother, but his composition of the spirited Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching, now almost better known as God Save Ireland, should entitle him to rank among the makers of living national music.

Scottish Music

After nine pages by J Muir Wood, Kidson adds:

George Thomson employed Pleyel, Kozeluch, Haydn, Beethoven, Weber and Hummel to harmonise and supply symphonies to the Scottish songs which comprised his published collections. The choice in all these instances was not very good. Beethoven appears to have been under the impression that the 'Scotch snap' was characteristic of all Scottish music, whereas, really, it only naturally belongs to the strathspey, the reel, and the Highland fling. Haydn, who seems truly to have had a liking for, and some knowledge of, Scottish vocal music, was certainly better fitted for the task; he also arranged the two volumes of Scottish songs issued by Whyte in 1806-7.

Sir G. A. MacFarren's collection has already been spoken of, and an excellent set of twelve Scottish songs arranged by Max Bruch was published by Leuckart of Breslau. Songs of the North, with the music arranged by Malcolm Lawson, had a great popularity, but many of the airs suffered a good deal in transmission, and several of them are to be found in a purer form in Macleod's Songs of a Highland Home.

The virulent attack made by the late Mr. William Chappell on the claims advanced for the Scottish origin of certain airs cannot in every case be considered justifiable. There is much truth in what he advances, i.e. that a number of Anglo-Scottish Songs of the 17th and 18th centuries have been too readily claimed as Scottish folk-songs, in spite of the fact that they have been sufficiently well ascertained to be the composition of well-known English musicians. See Chappell's Popular Music, old edition, pp. 609-616, etc.

It is, however, quite evident that Chappell's irritation has, on some points, led him astray; for some of his statements can be proved to be wrong; those for instance regarding Jenny's Bawbee, Gin a Body, and Ye Banks and Braes (q.v.), and some others. That Stenhouse, up to Chappell's time the chief writer on the history of Scottish Song, makes many lamentably incorrect assertions in his commentary on Johnson's Scots Musical Museum, cannot be denied, but that he did so wilfully is quite unlikely. It must be remembered that Stenhouse was handicapped by being four hundred miles from the British Museum Library, a storehouse which supplied Chappell so well, and besides, Stenhouse's work was a pioneer, for his notes were began in 1817. The late Mr. John Glen in his Early Scottish Melodies has much to say regarding Chappell's attack.

The question as to the antiquity of much of Scotland's national music is still undecided. The dates of manuscripts and of printed books, wherein such music first appears, are not a very trustworthy guide, for it is quite obvious that tradition has carried much of it over a considerable stretch of time, and also that music was built upon the modes, which remained in popular use for a long period after their abandonment in cultivated music. The existing manuscripts, none of which are prior to the 17th century, show that music-lovers of the day were well acquainted with English and Continental world and although there cannot be the slightest doubt that the common people played and sang purely national music, yet this was never written down until late times. Of the country songs mentioned in The Complaint of Scotland and other early works only few are to be recognised and identified with existing copies.

Another class of music which now constitutes part of the national music of Scotland was the compositions of professional or semi-professional musicians. As the fiddle is the national instrument of Scotland, so the reel and the strathspey reel are the national dances. A great number of country musicians, particularly in the northern part of Scotland, composed and played these dance tunes for local requirements. These they named either after some patron or gave them a fanciful title. In many instances, by the aid of subscription, the musician was enabled to publish one, or a series of his compositions, and so favourite dance tunes from these works were frequently reprinted and rearranged by other musicians.

Isaac Cooper of Banff, Daniel Dow, William Marshall, and many other lesser-known composers, along with the Gow family, have thus enriched Scottish music. We must also remember that where one of this type of musicians has succeeded in getting his compositions into print, there may be many whose tunes have passed into local tradition namelessly, so far as composer is concerned. While there are a great many beautiful and purely vocal airs, yet these instrumental melodies have largely been used by songwriters in spite of their great compass; this is one of the factors which makes Scottish song so difficult of execution to the average singer. Miss Admiral Gordon's Strathspey, Miss Forbes' Farewell to Banff, Earl Moira's Welcome to Scotland, with others, are well-known examples, and have been selected by Burns and other song-writers for their verses. Another notable one is Caller Herring, which, composed by Nathaniel Gow as a harpsichord piece (one of a series) intended to illustrate a popular Edinburgh Cry, had its words fitted twenty years afterwards by Lady Nairne.

In the '20s and '30s many now well-known songs in the Scottish vernacular had their birth, possibly owing to the Waverley Novels. Allen Ramsay was the first to collect the Scots Songs into book form from tradition, and from printed ballad sheets and garlands. His first volume of the Tea-Table Miscellany was issued in 1724, three others following later. It is rather unfortunate, from an antiquarian point of view, that Ramsay and his friends were not content to leave them as collected, but imparted to many a then fashionable artificial flavour, while boasting in his dedication of the charming simplicity of the Scotch ditties.

In 1769 and 1776 David Herd rendered a more trustworthy account of traditional Scots Song in the two volumes he published; while Johnson's Scots Musical Museum of six hundred songs with the music, was the principal collection of the 18th century.

The following list comprises all the important collections of Scotch National music including some early manuscripts which contain Scottish airs.

Printed and Engraved Collections:

Many Scots and Anglo-Scottish airs appear in Playford's Dancing Master 1650-1728, and other of Playford's publications, also in D'Urfey's Pills to purge Melancholy, 1698-1720. At later dates a great number are also to be found in the London country-dance books of various publishers.

The attention recently paid to folk-song has brought forth enough evidence to show that the published Scottish national music is but a small proportion of what, even now, exists in a traditionary form. Mr Gavin Greig, Miss Lucy Broadwood, and other workers, have, without much search, brought to light a wealth of Gaelic music of a purely traditional kind. In the Lowlands of Scotland folk-song exists as it does in England, and much of this lowland Scottish folk-song as either almost identical with that found in different parts of England, or consists of variants of it. There is, of course, a certain proportion which may be classed as purely confined to Scotland. One of the first of the modern attempts to tap this stream of traditional music was made by Dean Christie, who published his two volumes of Traditional Ballad Airs in 1870 and 1881. This collection of between three find four hundred tunes noted down with the words in the north of Scotland, would have been much more valuable if the Dean had been content to present them exactly as noted. Another valuable contribution to the publication of Scottish folk-song is Robert Ford's Vagabond Songs of Scotland, first and second series, 1899 and 1900. In both these works folk-song as known in England is largely present. The New Spalding Club of Aberdeen in 1903 made an initial movement towards the rescue of traditional Scottish song. Mr Gavin Greig (who is also a grantee under the Carnegie Trust given to the Universities of Scotland for research work) was commissioned to collect systematically in the north-east of Scotland. Mr. Greig's able paper, Folk-Song in Buchan, being part of the Transactions of the Buchan Field Club, gives some of the results of his labours. The Scottish National Song Society, recently founded, is also turning its attention to folk-song research.

Sellinger's Round

A 16th-century tune and round dance, of unknown authorship, which had immense popularity during the 16th and 17th centuries. The original form of the title was doubtless St. Leger's Round. The delightful vigour and unusual character of the air are felt today, when played before a modern audience, as fully as in its own period. It is frequently referred to in 16th and 17th century literature, including Bacchus Bountie, 1593; Morley's Plaine and Easie Introduction, l597, and elsewhere. In some cases the sub-title 'or the Beginning of the World' is found added to it, and this is partly explained in a comedy named 'Lingua,' 1607. An excellent version of the tune, arranged with variations by William Byrd, is found in the Fizwilliam Virginal Book and other copies of the air are in Lady Neville's Virginal Book and William Ballet's Lute-book.

Printed copies, which differ considerably, and are not so good as those referred to, appear in some of the Playford publications, including early editions of  The Dancing Master, Musick's Handmaid, and Musick's delight on the Cithren. The original dance has probably been a May-pole one, and this is borne out by a rude wood-cut on the title-page of a 17th century 'Garland,' where figures are depicted dancing round a may-pole, and 'Hey for Sellinger's Round' inscribed above them.

The Dancing Master, Musick's Handmaid, and Musick's delight on the Cithren. The original dance has probably been a May-pole one, and this is borne out by a rude wood-cut on the title-page of a 17th century 'Garland,' where figures are depicted dancing round a may-pole, and 'Hey for Sellinger's Round' inscribed above them.

Here is the air, without the variations and harmony, in the Fitzwilliam Book.

Sir Roger De Coverly

(or more correctly Roger of Coverly. The prefix 'Sir' is not found until after Steele and Addison had used the name in the Spectator).

The only one of the numerous old English dances which has retained its popularity until the present day, is probably a tune of north-country origin. Mr. Chappell (Popular Music, vol. ii.) says that he possesses a MS. version of it called Old Roger of Coverlay for evermore, a Lancashire Hornpipe, and in The First and Second division Violin (in the British Museum Catalogue attributed to John Eccles, and dated 1705) another version of it is entitled Roger of Coverly the true Cheisere way.  Moreover, the Calverley family, from one of whose ancestors the tune is said to derive its name have been from time immemorial inhabitants of the Yorkshire village which bears their name. The editor of the Skene MS., on the strength of a MS. version dated 1706, claims the tune as Scotch, and says that it is well known north of the Tweed as The Maltman comes on Monday. According to Dr. Rimbault (Notes and Queries, i. No. 8), the earliest printed version of it occurs in Playford's 'Division Violin' (1685). In The Dancing Master it is first found at page 167 of the 9th edition, published in 1695, where the tune and directions for the dance are given exactly as follows (right):

Moreover, the Calverley family, from one of whose ancestors the tune is said to derive its name have been from time immemorial inhabitants of the Yorkshire village which bears their name. The editor of the Skene MS., on the strength of a MS. version dated 1706, claims the tune as Scotch, and says that it is well known north of the Tweed as The Maltman comes on Monday. According to Dr. Rimbault (Notes and Queries, i. No. 8), the earliest printed version of it occurs in Playford's 'Division Violin' (1685). In The Dancing Master it is first found at page 167 of the 9th edition, published in 1695, where the tune and directions for the dance are given exactly as follows (right):

The Scots song, The Maltman comes on Monday, is not, as erroneously asserted by Chappell, by Allan Ramsay, although it is inserted in the first volume of his Tea-Table Miscellany, 1724. The English title is not so easily disposed of.

The Spectator, 2nd number, 1711, speaks of Sir Roger de Coverley as a gentleman of Wocestershire, and that 'His great grandfather was the inventor of the famous country dance which is called after him'.

Fanciful as this is, it shows that the dance at that time, was considered an old one. Another origin for the name of the tune is based on a MS. in the writer's possession inscribed 'For the violin, Patrick Cumming his Book: Edinburgh, 1723'. At the end the name is repeated, and the date 1724 given. The tune stands as follows (left), although the Scottish scordatura is likely to puzzle the casual reader, since the first notes which appear as G, A, B, C sound A, B, C, D. (see Scordatura.)

Fanciful as this is, it shows that the dance at that time, was considered an old one. Another origin for the name of the tune is based on a MS. in the writer's possession inscribed 'For the violin, Patrick Cumming his Book: Edinburgh, 1723'. At the end the name is repeated, and the date 1724 given. The tune stands as follows (left), although the Scottish scordatura is likely to puzzle the casual reader, since the first notes which appear as G, A, B, C sound A, B, C, D. (see Scordatura.)

It is well known that the name 'Roger' was bestowed upon the Royalists during the Civil war, and it is suggested that 'Coverly' is really a corruption of 'Cavalier'.

As the dance, later, was almost invariably used at the conclusion of a ball, it was frequently called 'The Finishing Dance'. See Wilson's Companion to the Ball-Room, c. 1816, and Chappell's Popular Music for the modern figure. According to an early correspondent of Notes and Queries, the tune was known in Virginia, U.S.A., as My Aunt Margery.

Stock and Horn

A rude musical instrument mentioned by early writers as being in use among the Scottish peasantry. It appears to have been identical with or similar to the Pibcorn (see vol. iii. p. 739).  The instrument is figured in a vignette in Ritson's Scotish Songs, 1794, also on the frontispiece to the editions of Ramsay's Gentle Shepherd illustrated by David Allen, 1788 and 1808.

The instrument is figured in a vignette in Ritson's Scotish Songs, 1794, also on the frontispiece to the editions of Ramsay's Gentle Shepherd illustrated by David Allen, 1788 and 1808.

It was then almost obsolete, for Robert Burns, the poet, had much difficulty in obtaining one. It appears to have been made in divers forms, with either wooden or a bone stock, the horn being that of a cow. Burns, in a letter to George Thomson, Nov 19, 1794, thus describes it:

Tell my friend Allan ... that I much suspect he has in his plates mistaken the figure of the stock and horn. I have at last gotten one; but it is a very rude instrument. It is composed of three parts, the stock which is the hinder thigh bone of a sheep ... the horn which is a common Highland cow's horn cut off at the smaller end until the aperture be large enough to admit the stock to be pushed up through the horn, until it be held by the thicker end of the thigh bone; and lastly, an oaten reed exactly cut and notched like that which you see every shepherd-boy have, when the corn stems are green and full grown. The reed is not made fast in the bones but is held by the lips, and plays loose on the smaller end of the stock; while the stock with the horn hanging on its larger end, is held by the hand in playing. The stock has six or seven ventages on the upper side, and one back ventage, like the common flute. This of mine was made by a man from the braes of Athole, and is exactly what the shepherds are wont to use in that country. However, either it is not quite properly bored in the holes, or else we have not the art of blowing it rightly, for we can make little of it.

The pipe is held by the left hand and fingered by it, while the tabor is hung by a ribbon on the left wrist and beaten with a small stick held in the right hand. The tabor appears to have varied in size. Some depicted in old prints, notably that of the pipe-and-tabor player in Kemp's Nine daies wonder, show the length of the tabor as about twice the diameter of the head, similar to that figured on p. 14 below, under the heading Tambourin.

Tarantella

After an entry on the traditional, modern and theatrical music and dance by W Barclay Squire, Kidson adds:

To the above it may be added that a curious account of the cure of a person bitten by the tarantula spider is given, in a letter signed Stephen Storace (the father of the better-known musician), in The Gentleman's Magazine, for Sept, 1753. Storace says that he was called upon to play the particular tune associated with the cure, but this he did not know, and tried sundry jigs without effect, until learning the proper tune from the lips of an old woman he played it with a satisfactory result. He gives the following (right) as the traditionary melody, and states that the scene of the occurrence was a village ten miles from Naples.

To the above it may be added that a curious account of the cure of a person bitten by the tarantula spider is given, in a letter signed Stephen Storace (the father of the better-known musician), in The Gentleman's Magazine, for Sept, 1753. Storace says that he was called upon to play the particular tune associated with the cure, but this he did not know, and tried sundry jigs without effect, until learning the proper tune from the lips of an old woman he played it with a satisfactory result. He gives the following (right) as the traditionary melody, and states that the scene of the occurrence was a village ten miles from Naples.