This was just one of the many changes in Traveller life-style that we saw in the following years.

This was just one of the many changes in Traveller life-style that we saw in the following years.

Musical Traditions Records' first CD release of 2003: From Puck to Appleby (MTCD325-6), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the records, or who might find the small print hard to read, we have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

I have included a few sound clips here, but not from any songs which first appeared on the VWML cassette 'Early in the Month of Spring', nor from any for which a single verse is over a minute in length. There are a good number of these, but I feel that most readers would have to wait longer than they would wish to for the download - and just a part of a verse would be ridiculous.

CD One | |||

| 1 - | Lady in Her Father’s Garden | Mary Cash | 5:15 |

| 2 - | Early in the Month of Spring | Mikeen McCarthy | 3:24 |

| 3 - | There is an Alehouse | ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors | 2:26 |

| 4 - | Donnelly | Mary Delaney | 2:53 |

| 5 - | Town of Linsburg | Mary Delaney | 5:40 |

| 6 - | The Half Crown | Andy Cash | 1:28 |

| 7 - | Charming Blue Eyed Mary | Mary Delaney | 5:45 |

| 8 - | Gum Shellac | ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors | 2:34 |

| 9 - | Constant Farmer’s Son | Josie Connors | 7:21 |

| 10 - | Sam Cooper | Bill Cassidy | 3:38 |

| 11 - | If Ever You Go to Kilkenny | Mary Delaney | 1:51 |

| 12 - | Go for the Water (Story) | Mikeen McCarthy | 2:38 |

| 13 - | The Sea Captain | Jean ‘Sauce’ Driscoll | 2:40 |

| 14 - | Fourteen Last Sunday | Mary Delaney | 4:09 |

| 15 - | Biscayo | Bill Cassidy | 6:44 |

| 16 - | Appleby Fair | ‘Rich’ Johnny Connors | 1:34 |

| 17 - | Peter Thunderbolt | Mary Delaney | 4:06 |

| 18 - | Going to Clonakilty the Other Day | Mary Delaney | 1:14 |

| 19 - | Buried in Kilkenny | Paddy Reilly | 3:45 |

| 20 - | Flowery Nolan | Mikeen McCarthy | 3:22 |

| 21 - | Poor Old Man | ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors | 1:37 |

| 22 - | In Charlestown there Lived a Lass | Mary Delaney | 3:37 |

Total: | 79:27 | ||

CD Two | |||

| 1 - | The Blind Beggar | Paddy Reilly | 4:32 |

| 2 - | Selling the Ballads | Mikeen McCarthy | 2:36 |

| 3 - | The Factory Girl | Bill Cassidy | 4:42 |

| 4 - | I’ve Buried Three Husbands Already | Mary Delaney | 1:39 |

| 5 - | John Mitchel | ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors | 4:45 |

| 6 - | Maid of Aughrim | Peggy Delaney | 2:35 |

| 7 - | My Brother Built Me a Bancy Bower | Mary Delaney | 2:55 |

| 8 - | Marie (Maureen) from Gippursland | Bill Bryan | 3:04 |

| 9 - | Pretty Polly | Bill Cassidy | 7:08 |

| 10 - | Rambling Candyman | ‘Rich’ Johnny Connors | 1:46 |

| 11 - | Green Grows the Laurel | Mary Delaney | 3:46 |

| 12 - | Barbary Ellen | Andy Cash | 4:46 |

| 13 - | The Kilkenny Louse House | Mary Reilly | 3:01 |

| 14 - | Malone (The Half Crown) | Mikeen McCarthy | 1:17 |

| 15 - | Finn MacCool and the Two-Headed Giant | Mikeen McCarthy | 4:49 |

| 16 - | Mowing the Hay | Andy Cash | 2:51 |

| 17 - | Phoenix Island | Mary Delaney | 2:00 |

| 18 - | Navvy Shoes | Mary Delaney | 3:50 |

| 19 - | Dingle Puck Goat | Mikeen McCarthy | 2:41 |

| 20 - | Enniscorthy Fair | Bill Cassidy | 3:53 |

| 21 - | New Ross Town | Mary Delaney | 2:57 |

| 22 - | One Fine Summer’s Morning | Mikeen McCarthy | 2:45 |

| 23 - | What will we do when we'll have no Money? | Mary Delaney | 1:57 |

Total: | 78:05 | ||

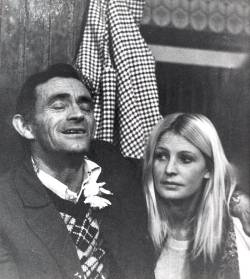

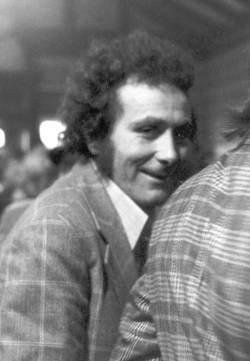

Katey Dooley (Mikeen McCarthy’s & Peggy Delaney’s younger sister)

talking about The Female Sailor, 1976.

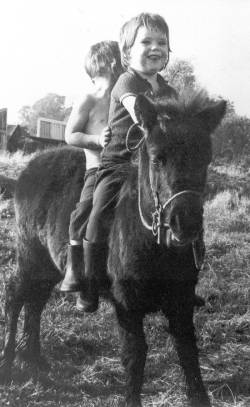

Puck, Appleby, Cahirmee, Ballinasloe, Southall; wherever there are horse fairs you will find Travellers. However, when we first made contact with Irish Travellers in 1973, only one family we met had a pony and, when they moved into London from Langley in Buckinghamshire, that had to go.  This was just one of the many changes in Traveller life-style that we saw in the following years.

This was just one of the many changes in Traveller life-style that we saw in the following years.

Before 1973, we had no idea there were so many Irish travellers living in London and the outskirts. We were amazed at the many caravan sites we found, often in the most unlikely places, and at the large number of singers, nearly all young, and at the size and content of their repertoires of traditional song. Until that time, the relative isolation of travelling life meant that, while traditional singing was in decline, it was in better condition than within most settled communities. One indication of this was to be found in the age of the singers. We had been used to traditional singers fairly advanced in years but we were finding the Traveller singers much younger, ranging in age from early twenties to mid forties.

Of the Travellers on these CDs, we were lucky in first meeting ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors, a man whose contacts with non-Travellers included Jeremy Sandford, to whose book, Gypsies, Johnny had contributed a chapter. He made us welcome and introduced us to several fine singers including his brother-in-law, Bill Cassidy. At that time, ‘Pop’s’ Johnny, together with Bill Cassidy, Mary Cash, Andy Cash and many more, were camped illegally under the Westway flyover in North Kensington. On being moved on, some went westwards and, around Langley, we met Mikeen McCarthy, his sister Peggy Delaney, daughter Jean ‘Sauce’ Driscoll, as well as Mary Delaney and Josie Connors. Paddy Reilly is Mary Delaney’s brother whom we met later in Camden Town. ‘Rich’ Johnny Connors was even further west, camped on a site outside Swindon.  (Delaney, Cash and Connors are fairly common Traveller names; none of these are closely related).

(Delaney, Cash and Connors are fairly common Traveller names; none of these are closely related).

When we first started recording them, together with Denis Turner, our aim was primarily to capture as many songs as possible. As our interest was with traditional songs, we wished to ascertain whether these were still part of Travellers’ repertoires and, if so, did they play any part in their everyday lives. Initially, therefore, we would ask if they had any old songs. While we later found they had many different types of songs, those they sang for our recording were mainly traditional or traveller made songs using traditional forms and tunes. They were well aware which were the ‘old’ songs or, as Mary Delaney called them, "me Daddy’s songs" (although in fact she had very few of his songs, which we were able to verify after meeting him). On several occasions, Mary expressed a strong preference for ‘the old songs’ and, while she could probably have doubled the number of songs she gave us with non-traditional ones, she persistently declined to do so saying that they were not the ones we wanted. She told us on one occasion that she only sang Country & Western songs because "that’s what the lads always ask for in the pub." Having sung from the age of four, Mary picked up songs very quickly, usually after two or three hearings.

Through the time spent talking with Travellers, we gained insight into the practice of traditional singing and to the significance that the songs had within the travelling community, a significance that appeared to go beyond the usually supposed one of just entertainment. They differentiated very positively between different types of songs and, while singers might have Country & Western, sentimental tear-jerkers, popular songs from an earlier time which they sang in pubs, they were well able to distinguish between them and to articulate this distinction.  (Incidentally, we were to find at a later date that Norfolk singer Walter Pardon made the same distinction; was well able to date his songs and spoke to us at length about his own relationship to the songs he sang).

(Incidentally, we were to find at a later date that Norfolk singer Walter Pardon made the same distinction; was well able to date his songs and spoke to us at length about his own relationship to the songs he sang).

Frequently, after pub closing time, groups would gather round a fire on the site to sing, tell stories and talk at great length on ‘the right way’ to sing these songs and ballads; to argue about style; who had the best songs and were the best singers; and to comment on the songs still being created. Many of the singers we met were highly vocal in their opinions on how the songs should be sung. This became particularly apparent one night in West Drayton when we were asked to judge between the singing of two brothers, both with repertoires gained from the same source, their parents. One had a highly developed traditional style, while the other leaned towards Country & Western and sang all his songs and ballads in that manner. Tactfully, we declined to comment.

Song-making was still to be found, as witnessed by the number of short pieces we recorded that must have been made up within the living memory of the singers, such as, Going to Clonakilty, Stash the Pavvies and occasionally longer ones like Old Cahirmee, which told of the trials and tribulations of a married couple who, we believe, are still around - hence its non-appearance here.

However, almost overnight it seemed, in the mid-seventies, the easy availability of the battery powered, portable television set put an end to the fireside gatherings.

"My father knew all that song; I knew it as well. Those other new type songs come out now; I never sing them now you see, you’ve missed them - you know what I mean."We did record other types of songs but have not included them. These CDs are not intended to be an academic study of Travellers’Bill Cassidy talking about Biscayo, 1973.

repertoires but are for the enlightenment and enjoyment of those interested in traditional songs and singers.

repertoires but are for the enlightenment and enjoyment of those interested in traditional songs and singers.

Apart from the songs, we also recorded a great deal of information on travelling life both in rural and urban Ireland and Britain; for instance, the old trades like tinsmithing, horse dealing, building and decorating the beautifully elaborate caravans, and many other occupations that have now disappeared. We had explained to us the superstitions (pishoges) and traditions, marriage practices, funeral customs, traditional games and sports along with a fair amount of the Travellers own language, Shelta or Gammon.

We had the opportunity to record some people on only one occasion, hence the lack of biographical information. This also meant that many recordings were not made in the best conditions, which explains the sound of trains, cars, dogs, children, etc. Other Travellers we were with for several sessions, and with two for considerable amounts of time.

Mary Delaney moved east right across London and even into various flats from time to time in order to give her children a better education. A lovely singer, mother of sixteen children and blind from birth, Mary has an enormous repertoire of outstanding songs and ballads that she has known since childhood, as well as a store of humorous yarns that gave us many hours of pleasure.

We have undoubtedly spent more time with Mikeen McCarthy than with anybody else. He, too, moved gradually across to East London and somehow we were always able to find him again after each shift. Storyteller and singer, we have recorded from him an incredible amount of information about travelling life and about the settled communities in rural Ireland. Now over seventy, Mikeen has lived in England for some fifty years but still retains vivid memories of his boyhood and youth in Co Kerry where he was born. Interestingly, one of his early occupations was having the song sheets, known in Ireland as ‘the ballads’, printed (by reciting the words to the printer) and selling them at fairs and markets, singing the songs in the streets and bars to publicise them. We are still in contact with Mikeen McCarthy and continued to visit and record him regularly until 1992.

The time we spent with Irish Travellers was most exciting and rewarding. We are very grateful to have had the opportunity to record and to have become good friends with so many. We shall never forget the warm hospitality and generosity shown to us and the wit and humour of the people we met. This compilation contains only a sample of the many recordings we have made of these and other Travellers, but we hope it will convey some small part of our thanks for the pleasure they have given us and for the invaluable role they have played in keeping the old songs alive.

Many recordings were not made in ideal conditions, hence the sound of trains, cars, dogs, children, etc. Copyright in all material resides with the performers.

Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie - 1.2.03

Child Numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child, 1882-98. Laws Numbers, where quoted, refer to entries in American Balladry from British Broadsides by G Malcolm Laws Jr, 1957.

Words shown in [square brackets] are either translations of dialect/cant words, or guesses/suggestions from another recording or standard text where the singer's word is unclear or obviously wrong.

At the end of the notes on each song is an indication of where (if at all) the song is available on CD by any other singer.

There being a lady in her father's garden,

A gentleman, he was passing by.

And he stood a while for to gaze all on her,

He said, "Fair lady, would you fancy I?"

"Oh no kind sir, I am no lady,

I'm but a poor girl of a low degree.

There before, young man, choose another sweetheart,

I'm not fitting for your slave to be."

"It is seven years since I had a sweetheart,![]()

And seven more since I did him see.

And seven more I'll wait all on him,

If he's alive he'll come home to me."

"Or maybe your love he is dead and drownded.

Or maybe your love he is dead and gone."

"Or if he is sick I'll wish him better,

And if he's dead I will wish him rest’."

Saying, "Lady, lady, I'm your own true lover,

I came from sea love, to marry you."

Saying, "If you’re my own and my single sailor,

Your face and features do look strange to me."

For he put his hand all in his pocket,

His lily-white fingers do look long and small,

And it's up between he pulled a gold ring,

And when she seen it to the ground she fell.

He picked her up all in his arms,

He gave her kisses most tenderly,

Saying, "I'm your own and your loyal true lover,

You're the only young girl that my heart love best."

Saying, "If I had you in those Phoenix Islands,

One thousand miles from your native home,

In some lonesome valley, love, between two mountains,

It’s there, sweetheart, I’ll call you my own."

"For I've a house; I've a good way living,

I've plenty of money for to spend on you,

And if you come there love, it's the lady I'll make you.

I’ll have some servants for to wait on you."

"You haven't me in those Phoenix Islands,

Neither one thousand miles from my native home.

Neither in that valley, love, between two mountains,

Nor later sweetheart you won’t call me your own."

This is probably one of the most popular of all the ‘broken token’ songs, in which parting lovers are said to break a ring in two, each half being kept by the man and woman. At their reunion, the man produces his half as a proof of his identity.

Robert Chambers, in his Book of Days, 1862-1864, describes a betrothal custom using a ‘gimmal’ or linked ring:

‘Made with a double and sometimes with a triple link, which turned upon a pivot, it could shut up into one solid ring... It was customary to break these rings asunder at the betrothal which was ratified in a solemn manner over the Holy Bible, and sometimes in the presence of a witness, when the man and woman broke away the upper and lower rings from the central one, which the witness retained. When the marriage contract was fulfilled at the altar, the three portions of the ring were again united, and the ring used in the ceremony’.

These ‘broken token’ songs often end with the woman flinging herself into the returned lover’s arms and welcoming him back, but the above version has it differently and, Mary Delaney, who also sang it for us, had the suitor even more firmly rejected:

"For it’s seven years brings an alteration,

And seven more brings a big change to me,

Oh, go home young man, choose another sweetheart,

Your serving maid I’m not here to be."

Ref: The Book of Days, Robert Chambers, W & R Chambers, 1863-64.

Other CDs: Sarah Anne O’Neill - Topic TSCD660; Daisy Chapman - MTCD 308; Maggie Murphy - Veteran VT134CD.

2 - Early in the Month of Spring (Roud 273, Laws K12) Mikeen McCarthy

Oh, ‘twas early, early in the month of spring,

When my love Willie went to serve the king;

The night was dark and the wind blew high,

Oh, that parted me from my sailor boy.

"Oh, then, father, father, build me a boat,

It’s on the ocean I mean to float,

To watch those big boats as they pass by;

Have they any tidings of my sailor boy?"

Oh, she was not sailing but a day or two,

When she spied a French ship and all her crew,

Saying, "Captain, Captain, come tell me true,

Oh, does my love, Willie, sail aboard with you?"

"Oh, what colour hair has your Willie dear?

What kind of clothes do your Willie wear?"

"He’ve a bright silk jacket and it trimmed all round,

And his golden locks they are hanging down."

"Oh, indeed, fair lady, your love is not here,

For he is drownded, I am greatly feared,

For in yon green island as we passed by,

Oh, we lost nine more and your Willie boy."

Oh, she wrung her hands and she tore her hair,

She was like a lady all on despair,

She dashed her small boat against the rocks,

Saying, "What will I do if my love is lost?"

Oh, I’ll write a letter and I’ll write it long,

In every line I will sing a song,

In every line I will shed a tear,

And in every verse I’ll cry, "Willie dear."

"Oh, then, father, father, dig me my grave,

Oh, dig it long, both wide and deep,

Put a headstone to my head and feet,

And let the world know it was in love I died."

English folk-song scholar, A L Lloyd, in his note to the Sussex version of this, entitled A Sailor’s Life, pointed out that this is often combined with Died For Love, although he held them to be two different songs. He might also have added that is has become entangled with several other songs, including The Butcher Boy and Black is the Colour.

The evocative ‘month of spring’ opening line can also to be found in the version recorded from Traveller Lal Smith in 1952, which is hardly surprising as Mikeen and Lal’s families were closely associated in Mikeen’s youth. Lal’s father, Christie Purcell, was a showman who, among other occupations, ran a travelling theatre company (known in Ireland as a Fit-Up). They performed plays such as East Lynne and Murder in the Red Barn around the towns and villages of rural Kerry in the nineteen thirties and forties and Mikeen and his three sisters participated in the productions as stage crew and as actors.

Mikeen learned the song from his father’s singing and it was one that he sold on a ballad sheet when he was involved in that trade as a young man.

Ref: The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, R Vaughan Williams and A L Lloyd (eds.), Penguin Books. 1959.

Other CDs: Liz Jeffries - Topic TSCD 653; Phoebe Smith - Topic TSCD 661; Harry Cox - Rounder CD 1839.

3 - There is an Alehouse (Roud 60, Laws P25) ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors

There is an alehouse all in Bray town,

Where my love Willie goes and sits down.

He will take a strange girl on his knee,

And he'll tell her things that he won't tell me.

For now I know, oh, the reason why,

Because that fair girl has more gold than I.

That her silver may melt, may her gold fly,

And she'll see the day she'll be as poor as I.

I wished, I wished, I wished in vain;

Sure I wish to God I was a fair maid again.

For that's a sight that I never might see,

Until apples grow 'pon an ivy tree.

I wished, I wished my babe was born,

And sitting on his daddy’s knee.

Oh is that's the sight that I never might see

'til shamrocks grow 'pon a lilac tree.

This is usually known as Died For (or of) Love. The note to the versions collected for the BBC between 1952 and 1957 reads: ‘As Sharp rightly observed, this is one of the most popular of English folk songs and it is one from which many fragmentations have been made, to survive as separate songs, some being difficult to identify, as several of the verses are commonplace… An American student version, supposed originally to have been collected in Cornwall, has been popularised as Tavern in the Town’.

We recorded There is an Alehouse on several occasions from travellers. ‘Pop’s’ Johnny’s text gives the reason for the girl’s rejection as being ‘lack of money’, while others deal only with her being pregnant. We recorded a version of The Butcher Boy (Roud 409, Laws P24) from a young travelling woman, Bridie ‘Dolly’ Casey, which includes the first ‘Alehouse’, verse.

Ref: BBC Recordings of Folk Music and Folklore, Great Britain and Ireland, Section 1: Songs in English.

Other CDs: Jasper Smith, Amy Birch - Topic TSCD 661; Geoff Ling - Topic TSCD 660; May Bradley - Topic TSCD 662; Sarah Porter - MTCD309-10.

4 - Donnelly (Roud 863) Mary Delaney

There was a jolly knacker* and he had a jolly ass,

And he stuffed his box of pepper up the jolly asses arse.

Oh then, brave done Donnelly, good enough, says she,

Oh then, well done Donnelly, and you're my man, says she.

There was an old woman in the corner over eighty years or more.

And, "For God Almighty's sake", she says, "will you solder my old po?"

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, good enough", says she.

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, and you’re my man", says she.

I soldered in the kitchen and I soldered in the hall,

And when I finished soldering I done the ladies and all.

Oh then, "Brave ould Donnelly, good enough", says she.

Oh then, "Brave O’Donnelly, and you’re my man", says she.

She sent me up the stairs for to dress the tinker’s bed,

The jolly knacker followed after me and tripped me on the leg.

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, good enough", says she.

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, and you’re my man", says she.

If you’re an honest woman as I took you for to be,

You’d have a basket on your arm and a kid belonging to me,

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, good enough", says she.

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, and you’re my man", says she.

I am a jolly tinker oh, for ninety years or more;

And a divil a finer job, me lad, I never done before.

Oh then, "Brave ould Donnelly, g’out that sir", said she.

Oh then, "Well done Donnelly, and you’re my man", said she.

[* Knacker: Originally a horse for slaughter but also used for tinsmith (often now a general word for traveller).]

This is one of the many songs in the tradition telling how the underdog turns the tables on his/her supposed superiors by using their sexual prowess.

An early version of this appeared in 1616 in a collection entitled Merry Drollery, as Roome for a Jovial Tinker or Old Brass to Mend; it was later included in John Farmer’s Merry Songs and Ballads.

The ‘box of pepper’ in Mary’s first verse refers to a practice once carried out by unscrupulous horse dealers, of livening up a docile horse for sale by applying pepper or mustard to the appropriate part of the unfortunate animal’s anatomy.

Ref: Merry Songs and Ballads, John S Farmer, 1897, Privately printed.

Other CDs: Thomas Moran - Rounder CD 1778.

5 - Town of Linsborough (Roud 263, Laws P35) Mary Delaney

I’m belonging to Dublin City,

And a city ye all know well.

My parients reared me tenderly

And brought me up quite well.

‘Twas near the Town of Linsborough

Where they bound me to a mill;

It was there I beheld with a comely maid

With a dark and rolling eye.

She promised me she'd marry me

And with her I dwell;

At twelve o'clock that very same night

When I entered her sister’s door.

"Come out, come out, my joy and fair maid

And take a walk with me,

And then we'll sit and chat a while

And 'point our wedding day".

‘Twas with his false and inluded tongue

He coaxed that fair maid out,

And ‘twas from the ditch he broke a stick

And he knocked that fair maid down.

She went down on her bare bended knees,

For mercy she loudly cried,

Oh, saying, "Willie dear, do not murder me,

And I not fit to die".

Then he catched her by those yellow locks

And drew her along the ground;

He catch her by the yellow locks

And drew her along the ground,

‘Til he drew her to a river

Where her body could not be found.

Returning home to his master's house

At twelve o'clock that night,

Saying, asking for a candle

For to show himself some light.

His master boldly asked him,

"What stained your hands and clothes?"

Look how quick he made him an answer,

"I'm bleeding from the nose".

He went into bed, no more was said,

Neither rest nor peace could find,

Only the murder of that fair young maid

Laid heavy on his mind.

Now he was arrested and taken

And tried in London Town.

And the villain, he was transported

And his reverence come home free.

According to John Harrington Cox, The Wittam Miller is said to describe a murder that took place in 1744 in Reading, in Berkshire, though there are two broadsides dating from sixty and forty-four years earlier with similar titles. An excellent account of how this has been shaped by time and tradition from a long, ungainly broadside entitled The Berkshire Tragedy or The Wittam Miller, to the concise piece that it has become, is to be found in Malcolm Laws’ American Balladry from British Broadsides.

The ballad has travelled widely through Britain, Ireland and particularly America, where it proved hugely popular with country singers and has given rise to other songs on the same theme, for instance Down by the Willow Garden and Omie Wise.

It has been found under many titles, which often identify the place where the murder was supposed to have been committed: The Wexford, Waterford, Oxford, or Lexington Girl to name a few. The murderer has been given a variety of occupations: butcher, printer, miller, or simply apprentice.

Mary’s version is fairly typical of many of the Irish and American texts with the exception of the last line, which is somewhat confusing. In most texts the murderer is found guilty and hanged, but here Mary has used the last line of Father Tom O’Neill (Roud 1013, Laws Q25), an incomplete 8 verse set of which she has in her repertoire. In another recording we made of this, she sang as her two last lines:

His sentence was for his life and then he'd have to settle down,

For no more was said with the treasury only he did go down.

She was unable to explain the meaning of this and it is possible that she had extemporised it.

Linsborough is possibly Lanesborough in Co Longford.

Ref: American Balladry from British Broadsides, G Malcolm Laws Jnr, American Folklore Society, 1957; Folk Songs of the South, John Harrington Cox, Havard Univ Press, 1925.

Other CDs: Harry Cox - Topic TSCD 512D.

6 - The Half Crown (Roud 16988) Andy Cash

For I am an old widder, I’m fed up of life.

For years I am out looking for an old wife,

And I married as a widder but not settled down

And I'll do my endeavourings to make a half crown.

The population of Eireans is now getting small,

When young deValera steps in from the dawn,

And the laws that he's passed and he's now let them down,

For every child born he'd give a half crown.

The first night we started, we were nearly stone dead.

The next night we broke down the springs of th'ould bed,

And, "Begod then", said she, "and for I'm sixty three."

And, "Begod then", said he, "there's no half crown for me."

I woke the other night between midnight and dream,

What did I hear but a young baby scream.

And me wife she shouts out, "Get a bottle, you clown,

For little you knew you would make a half crown."

For now I resemble a half hungry goose,

Every bone in me body and joint it is loose.

And the neighbours all laugh and they call me a clown,

"It’s because of you’ll get that bloomin' half crown."

A Children’s Allowance of two shillings and sixpence for each child, introduced by Eamon deValera’s newly elected Fianna Fáil government in the early 1930s, gave rise to a number of songs and poems, and gave the term ‘making a half crown’ a special meaning. This is one of those songs.

7 - Charming Blue Eyed Mary (Roud 3230) Mary Delaney

As I strayed out on a May, May morn,

To view those flowers that were springing;

Who did I spy but a comely maid,

And sweetly she was singing.

"Where are you going my dear", he says,

"Or where are you going so early?"

"I’m going to milk, kind sir", she says,

"And I then must mind my dairy."

"May I go with you kind sir?" she says, [he]

Nice and comely he asked her.

"Yes, if you please sir, if you have time,

And I then can mind my dairy."

As they both sat down on a primrosy bank,

And thought there was no one near them,

Three times he kissed her rosy lips,

And those words to her he spoke then.

He handed her a diamond ring

Saying, "Take it as a token."

Six long months were passed and gone, ![]()

And no letter came for Mary.

Often she viewed her diamond ring

As she stood in her dairy.

As Mary went walking those meadows fair,

On a bright summer’s morning early,

When that same young man stepped up to her,

And he says, "Is this my Mary?"

"Come with me my dear", he says,

"And forsake your cows and your dairy.

I came from seas for to wed with you;

You’re my charming blue eyed Mary."

Mary went with him without delay,

Forsaked her cows and her dairy,

But now she is a sailor's wife;

She's his charming blue eyed Mary.

Apart from numerous broadside and chapbook texts, and a version recovered from a Newfoundland singer, we have been able to trace only two other versions of this, both from the Northern Ireland. One is from Inishowen, from John McDaid of Buncrana, and the other is in the Sam Henry collection and was obtained from John M’Neill in 1938, who got it from his grandfather, John Rankin of Knockmult, in Co Derry.

Ref: My Parents Reared Me Tenderly, Jimmy McBride (ed), Private publication, 1985; Sam Henry’s Songs of the People, Gale Huntington, (ed.), Univ of Georgia Press, 1990

8 - Gum Shellac (Roud 2508) ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors

We are the travelling people like the Picts or Beaker Folk,

The men in Whitehall thinks we’re parasites but tinker is the word.

With our gum shellac alay ra lo, move us on you boyoes.

All the jobs in the world we have done,

From making Pharaoh's coffins to building Birmingham.

With our gum shellac ala lay sha la, wallop it out you heroes.

We have mended pots and kettles and buckets for Lord Cornwall,

But before we'd leave his house me lads, we would mind his woman and all.

With our gum shellac alay ra la, wallop it out me hero.

Well I have a little woman and a mother she is to be,

She gets her basket on her arm, and mooches the hills for me.

With our gum shellac alay ra la, wallop it out me hero.

Dowdled verse.

We fought the Romans, the Spanish and the Danes,

We fought against the dirty Black and Tans

and knocked Cromwell to his knees.

With our gum shellac alay ra la, wallop it out me heroes.

Well, we’re married these twenty years, nineteen children we have got.

Ah sure, one is hardly walking when there's another one in the cot.

Over our gum shellac alay ra lo, get out of that you boyoes.

We have made cannon guns in Hungary, bronze cannons in the years BC

We have fought and died for Ireland to make sure that she was free.

With a gum shellac ala lay sha la, wallop it out me heroes.

We can sing a song or dance a reel no matter where we roam,

We have learned the Emperor Nero how to play the pipes, way back in the days of Rome.

With our gum shellac ala lay sha la, whack it if you can me boyoes.

Dowdled verse.

‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors, the singer of this song, is also the composer. He was an activist in the movement for better conditions for Travellers in the 1960s and was a participant in the Brownhills eviction, about which he made the song, The Battle of Brownhills, which tells of an unofficial eviction in the Birmingham area which led to the death of two Traveller children. An account of part of his experiences on the road is to be found in Jeremy Sandford’s book Gypsies under the heading, Seven Weeks of Childhood. This was written while Johnny was serving a prison sentence in Winson Green Prison in the English Midlands. He said that further chapters of an intended biography were confiscated by the prison authorities and never returned to him on his release.

Gum shellac is a paste formed by chewing bread, a technique used by unscrupulous tinsmiths to supposedly repair leaks in pots and pans. When polished, it gives the appearance of a proper repair but, if the vessel is filled with water, the paste quickly disintegrates, giving the perpetrator of the trick just enough time to escape with his payment.

Ref: Gypsies, Jeremy Sandford, Secker and Warburg, 1973

9 - Constant Farmer’s Son (Roud 675, Laws M33) Josie Connors

There being a lovely lady

Near Limerick town did dwell,

She was admired by lords and squires,

Her parents loved her well;

She was modest fair and handsome,

With all her hopes in vain,

There being but one, a farmer’s son,

That young Mary’s heart could gain.

For a long time Willie courted her

And appointed the wedding day,

But all of her parents gave consent

And the brothers they did say:

"There is one young lord have placed his word

And him you shall not shun,

For we’ll betray and we will slain

Your constant farmer’s son."

There being a fair not far from there,

The brothers went straight away,

And asked young Willie’s company

With them to spend the day.

The day being gone and the night rolled on,

They said, "Your race is run."

‘Twas with two sticks they took the life

Of my constant farmer’s son.

As Mary lay on her pillow soft,

She had a sadful dream,

She dreamed she seen her own true love

Lying by a russell stream.

She then have ‘rose, put on her clothes,

To seek her love she run.

‘Twas pale and cold she did behold

Her constant farmer’s son.

The tears rolled down her cherry cheeks

And mingled in her gore, [his]

And to replease her troubled mind,

She kissed him more and more.

She got the green leaves from the tree

To shade him from the sun,

Three nights and days she passed away

With her constant farmer’s son.

'Til hunger it crept over, poor girl

Fell down in grief and woe,

And to acquaint her parents,

It is home straight away she did go.

"Oh, parents dear, you soon shall hear

The dreadful deed that is done,

In yon green vale lies cold and pale

My constant farmer’s son."

Up steps the youngest brother

Who says, "It was not me."

The same reply the other, aye,

Who swore most bitterly.

Young Mary says, "Don’t be afraid

To try the law to shun.

Youse done the deed and youse shall bleed

For me constant farmer’s son."

Oh, now the two are taken

And locked all in a cell,

Surrounded by cold irons, aye,

And their sad face to be seen.

The jury found them guilty

And for the same were hung;

In a madhouse cell, young Mary did dwell,

For her constant farmer’s son.

The plot of The Constant Farmer’s Son was used in the 14th century by Boccaccio in The Decameron and later made the subject of poems: by Nuremberg poet Hans Sachs in the 16th century and, in the early 19th century, by John Keats in his Isabella and the Pot of Basil.

Based on an older song, The Bramble Briar or Bruton Town, which has been described as ‘probably the song with the longest history in the English tradition’, it owes its continued popularity to its appearance on nineteenth century broadsides. A version from Hertfordshire in 1914 gives it as ‘Lord Burling’s (or Burlington’s) Sister or The Murdered Serving Man.

As well as being found widely in England, it is very popular in Ireland, though it has only appeared in print there a couple of times. It is included in the Sam Henry Collection which gives four sources and, more recently it was included in Fermanagh singer John Maguire’s autobiographical Come Day, Go Day, God Send Sunday. Josie learned it from her mother, a Dublin Traveller.

Ref: Sam Henry’s Songs of the People, Gale Huntington (ed), Univ of Georgia Press, 1990; Come Day, Go Day, God Send Sunday, Robin Morton (collator), Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1973

10 - Sam Cooper (Roud 16726) Bill Cassidy

For my name is Sam Cooper; I'm up for a crime,

I'm 'rested and taken by one Larry Bryan.

For they couldn't find me guilty on every degree,

Nor Bryan and his swearing made no fist in me.

Raddlum, fol the diddle eral, try erol try ay.

Coming back from Ogree and the sky it got black,

Saying I knew I'd get captured before I'd get back,

Now they followed me on after; they followed me on still,

I was handcuffed and caught on the house on the hill.

Raddlum, fol the diddle eral, try erol try ay.

Now they brought me to Timmum* to try me one day

Between 'tourney O'Connor and twelve jurymen;

When they couldn't find me guilty, the court it did smile

When they see poor Sam Cooper talking out of his time.

Raddlum, fol the diddle eral, try erol try ay.

Now they brought me to Wexford to try me again,

Between 'tourney O'Brennan and twelve jurymen.

Now they couldn't find me guilty on every degree,

Nor poor Bryan and his swearing made no fist in me.

Raddlum, fol the diddle eral, try erol try ay.

Now the court it is over, we're turning for home

And I'll make Lar’ repent now for all he have done.

One hundred won’t clear him to settle with me,

And I'll nail him again when I get liberty.

Raddlum, fol the diddle erol, try erol try ay.

Now they brought me to Enniscorthy to try me this day

Between 'tourney O'Connor and twelve jurymen,

When they didn't find me guilty, that court it did smile

When they see Sam Cooper walking out of his trial.

Raddlum, fol the diddle erol, try erol try ay.

Now the court it is over, I’m free one ‘gain,

And I’ll make this Lar’ now repent now for all he got done.

One hundred won’t clear him to settle with me,

I’m going to nail him again when at my liberty.

Raddlum, fol the diddle erol, try erol try ay.

[*Taghmon, Wexford]

We were unable find a printed text of this, and it appears to have been exclusive to travellers. We recorded it from three different singers and in each case they told us that Sam Cooper was arrested for stealing oats, though this is not mentioned in any of the versions. They also said that he was guilty as charged.

11 - If Ever you Go to Kilkenny (Roud 16989) Mary Delaney

If ever you’ll go to Kilkenny

Enquire for the Hole-in-the-Wall

And it’s there you'll get eggs for a penny

And butter for nothing at all.

Where the governor, he come round in the morning,

And a can of new milk in his hand,

And a dish of brown bread in his arm,

Three noggins for every poor man.

Three lines of tune lilted.

There’s no one knows that as good as me.

I went in there it was on last Friday

And I was very well drunk,

For he opened and loosened his laces.

"Bejasus", says I, "Take your time."

"Leave me and then me old trousers."

"Oh no", says the governor to me,

"You must strip and give me your clothing,

Then you can't wear them going in here."

With your right full aye doodle aye andy,

And right full aye doodle aye dee,

And right full aye doodle aye dandy,

There's no-one comes in here but me.

The Hole in the Wall was, from the middle of the eighteen century to 1850, one of Ireland's more renowned supper-houses, which numbered among its clientele, Sir Jonah Barrington, Henry Flood, the Duke of Wellington, Henry Grattan and Thomas Moore. Built in Tudor times, it still stands behind the High Street in Kilkenny, though it is now derelict. It is mentioned in a popular song composed in its heyday:

If ever you go to Kilkenny,

Remember the hole in the wall,

You may get blind drunk for a penny

Or tipsy for nothing at all.

There was another Hole in the Wall in Kilkenny, a hundred yards down the High Street from the eating house, in a narrow passage named The Butter Slip where, before the existence of the public market, farmers used to sell butter, eggs and other farm produce. It is quite possible that Mary’s song refers to this latter location although her text gives the impression that the premises referred to was a prison. She got it from her grandfather and said it was made by him.

Ref: Historic Kilkenny, Joseph H O’Carroll, Privately printed, 1978

12 - Go for the Water (Story - Aarne-Thompson 1351:The Silence Wager) Mikeen McCarthy

There was a brother and sister one time, they were back in the West of Kerry altogether, oh, and a very remote place altogether now. So the water was that far away from them that they used always be grumbling and grousing, the two of them, now, which of them’d go for the water. So they’d always come to the decision anyway, that they’d have their little couple of verses and who’d ever stop first, they’d have to go for the water. So, they’d sit at both sides of the fire, anyway, and there was two little hobs that time, there used be no chairs, only two hobs, and one’d be sitting at one side and the other at the other side and maybe Jack’d have a wee dúidín (doodeen), d’you know, that’s what they used call a little clay pipe (te). And Jack’d say:

(Sung)

Oren hum dum di deedle o de doo rum day,

Racks fol de voedleen the vo vo vee.

So now it would go over to Mary:

Oren him iren ooren hun the roo ry ray,

Racks fol de voedleen the vo vo vee.

So back to Jack again:

Oren him iren ooren hum the roo ry ray,

Rack fol de voedleen the vo vo vee.

So, they’d keep on like that maybe, from the start, from morning, maybe until night, and who’d ever stop he’d have to go for the water.

So, there was an old man from Tralee, anyway, and he was driving a horse and sidecar, ‘twas… they’d be calling it a taxi now. He’d come on with his horse and sidecar, maybe from a railway station or someplace and they’d hire him to drive him back to the west of Dingle. So, bejay, he lost his way, anyway. So ‘twas the only house now for another four or five miles. So in he goes anyway, to enquire what road he’d to take, anyway, and when he landed inside the door, he said: "How do I get to Ballyferriter from here?" And Mary said:

(Sung verse)

So over he went, he said, "What’s wrong with that one, she must be mad or something", and over to the old man. He said, "How do I get to Ballyferriter from here?"

(Sung verse)

So he just finished a verse and he go back over to Mary and he was getting the same results off of Mary; back to Jack. So the old man, he couldn’t take a chance to go off without getting the information where the place was, so he catches a hold of Mary and started tearing Mary round the place. "Show me the road to Ballyferriter", he go, and he shaking and pushing her and pull her and everything:

(Sung verse)

And he kept pulling her and pulling her and tearing her anyway, round the place, and he kept pucking her and everything.

"Oh, Jack," says she, "will you save me?"

"Oh, I will, Mary," he said, "but you’ll have to go for the water now."

Mikeen’s story, set in his own native Kerry, is widely travelled, both as a tale and as a ballad. A version from India, entitled The Farmer, his Wife and the Open Door is described as claiming ‘the highest possible antiquity’. It is also included, as part of a longer story, in Straparola’s Most Delectable Nights (Venice 1553). In Britain it is popular in ballad form, best known in Scotland as Get Up and Bar the Door and in England as John Blunt.

Mikeen has a large repertoire of stories, at least half a dozen of them having Jack and Mary as hero and heroine.

Ref: Folk Tales of All Nations, F H Lee, George G Harrap & Co, 1931.

13 - The Sea Captain (Roud 3376) Jean ‘Sauce’ Driscoll (daughter of Mikeen McCarthy)

For once there lived a captain

Who was borned out on sea;

And before that he got married

He was sent far away.

All on his returning

Up to his sweetheart's cottage he goes.

Straight up to her old, aged father,

And he knocked on the door.

Saying, "Is your daughter inside sir,

Can I see her once more?"

"Your true love's not inside sir,

For she left here last night.

She is gone to some annunery."

Was the old man’s reply.

For he went up into the nunnery

And he knocked all on the door,

Out comes the reverend mother

And she sweeping the floor.

Saying, "Your true love, she's not inside sir,

She left here last night,

She's gone to some asylum."

Was the reverend mother's reply.

For he went up into the 'sylum

And he knocked on the door,

Out comes the innkeeper

And his tears in galore.

Saying, "Your true love she is inside sir,

She died here last night,

She came from some annunery."

Was the old man's reply.

"Oh let me in", cried the captain,

"Let me in", the captain cried.

"Oh let me in", cried the captain,

"'Til I die by her side."

To our knowledge, the only other two versions to have been found in the tradition are from Seán Ó Conaire of Rosmuc, Co Galway and from Traveller John ‘Jacko’ Reilly of Roscommon.

We first recorded this from the singer’s father, Mikeen McCarthy, who had sold it around the fairs and markets in Kerry on a ballad sheet some time in the nineteen-forties. Unfortunately, he was only able to remember four verses and we tried on a number of occasions, without success, to see if he could recall more. One evening, he proudly announced that his daughter, a young woman then in her early twenties, had learned all of it from another Traveller, Nora Coffey. To our knowledge, this is the only traditional song she sings.

Other CDs: John Reilly - Topic TSCD 667.

14 - Fourteen Last Sunday (Roud 1570) Mary Delaney

"I was fourteen years last Sunday, mamma,

I’m longing for to be wed,

In the arms of some young man’d

‘D comfort me in bed,

In the arms of some young man

Would roll with me all night,

I’m young and I’m airy and bold contrary

And buckled I’d long to be."

"Hold your tongue, dear daughter," she says,

"I was forty when I was wed,

And that it was no shame for me

To carry me boss into bed."

"For if that was the way with you, Mamma,

It is not the way with me,

I’m young and I’m airy and bold contrary

And buckled I’d like to be."

"Hold your tongue, dear daughter," she says,

"And I will buy you a sheep."

"No, indeed, Mamma," she says,

"That would cause me for to weep,

To weep and weep and weep, Mamma,

It’s the thing I never can do."

"For I’ll send you down to the meadows all day

And I’ll stop you from drinking tea."

"Hold your tongue, dear daughter," she says,

"And I will buy you a cow."

"No, indeed, Mamma," she says,

"’Twould cause me for to vow,

To vow, to vow and vow, Mamma,

That’s a thing I never will do.

I’m young and I’m airy and cracked and contrary

And buckled I’d long to be."

"Hold your tongue, dear daughter," she says,

"And I will buy you a man."

"Do, indeed, dear Mother," she says,

"For the sooner the better you can,

For if that is the way with you, mamma,

It is not the way with me.

I’m young and I’m airy and bold contrary

And buckled I’d like to be."

This is better known under the title Whistle Daughter, Whistle, although Mary’s text lacks the whistling motif. Cecil Sharp collected it twice in England and once in America, but the texts he published were heavily edited.

It appeared frequently in collections of children’s games; William Wells Newell in his Games and Songs of American Children claimed it to be ancient and pointed out its similarity to 15th and 16th Century Flemish, German and French rounds in which a monk or a nun is tempted to dance by various offers.

Tom Lenihan, a farmer from Co Clare, sang it for us in 1977; his was also whistle-less. The only Irish version in print is to be found in Joyce’s Ancient Irish Music. This is a re-written, bowdlerised text accompanied by the following note:

‘I remember three stanzas of a song to this air. The conception and plan are good, but two of the verses are too coarse for publication; and even the one I give had to be softened down in one particular word. I will give the song a new dress. The three verses are retained, as little altered as possible, and even the old rhymes are preserved. I have endeavoured also to carry out the original spirit and conception’.

Ref: Games and Songs of American Children, William Wells Newell, Harper and Brothers, 1883; Ancient Irish Music, Patrick Weston Joyce, M H McGill and Son, 1906.

15 - Biscayo (Roud 179, Child 248) Bill Cassidy

For he come creeping when I being sleeping,

Down to my old window, was down so low,

Saying, "Who is that at my old bedroom window

That is knocking so boldly and can’t get in."

"For I am here, I’m your own true,

I am here this three long hours and can’t get in."

Saying, she raised up from her soft down pillow,

She’ve opened th’ould door lads, and she’ve let him in.

And with love and kisses how they blessed each other,

Oh, when this long night being slipping in.

Saying, "I must go, I can stay no longer,

For I’m only th’ould ghost of your ould Willie O."

Saying, "What have took your old lovely blushes,

Or whatever ate your grand cheeks away?"

"For th’ould cold, cold sea took my lovely blushes,

And it’s the worms ate my ould cheeks away."

"I must go, I can stay no longer,

Into a bay called Biscayo.

Where I’ll be guarded without hand or pilot,

For I’m but the ghost of your Willie O."

"I must cross o’er th’ould burning mountains,

That’s in to that bay called Biscayo.

That’s where I’ll still be guarded*, ah, without hand or any pilot,

That’s why I’m th’ould ghost of your ould Willie O."

[* guided]

We have always thought this song to be a version of The Grey Cock, (Child 248); however, ballad scholar Dr Hugh Shields has cast serious doubt on this assumption. In two detailed articles on the subject, he argues convincingly that it is a version of a nineteenth century Irish broadside entitled Willie O, the main source of which appears to be Sweet William’s Ghost (Child 77).

We have also recorded it from another traveller, Katie Dooley; and from West Clare singer Nora Cleary. Katie Dooley’s text, similar to Nora Cleary’s, has obviously evolved from the broadside, but Bill Cassidy’s text and tune are reminiscent of the well-known version entitled The Grey Cock which was recorded in the early 1950s from Mrs Cecilia Costello, a Birmingham woman of Galway parentage. Whatever the truth of the matter, all three have in common the lover returning from the dead and the couple’s time together being brought to a close with the crowing of the cock.

Both Mrs Costello’s and Bill’s versions have powerful images symbolising the difficulty of the dead returning; in Mrs Costello’s, the lover has to cross ‘the burning Thames’, while in Bill’s it is ‘the burning mountains’. Unusually, Katie Dooley’s version ends with the woman’s death and leaves her ‘sleeping beneath the billows’. This may be a mistaken substitution of she for he, but it makes perfect sense in the context of the song.

Bill was one of a number of Travellers who liberally scattered the word ‘old/ould’ into the texts of his songs!

Ref: Dead Lover’s Return in Modern English Ballad Tradition, Dr Hugh Shields: Jahrbuch Fur Volkliedforschung, 1976; Grey Cock: Dawn Song or Revenant, Hugh Shields, Ballad Studies, Folklore Soc. Mistletoe Series, 1976.

Other CDs: Nora Cleary - Topic TSCD 653; Cecilia Costello - Rounder CD 1776.

16 - Appleby Fair (Roud 16699) ‘Rich’ Johnny Connors

'Tis in Appleby Top you will find a horse fair,

Which it brings all those Travellers yes, year after year.

You'll see all those dealers, both diddys* and liars,

Sat cooking their scran* around smoky wood fires.

They’ll have piebalds and stewbalds and flea bitten greys,

Like the most of their own, sure, they've seen better days,

With a greasy-heel* here, and a bog-spavine* there,

We'll take knacker-prices* for those at the fair.

Sure you all know old Bob Ferris, and young Billy Brough,

Sure, they've all had it off and they sold some good stuff,

Between wibbling and wobbling, and speaking of grai*,

Sure, we will be thinking of Appleby Fair.

But you all know Dan Mannion, he's a man who is game,

Sure, he kept trotting horses which have brought him great fame,

In company with Chick, which he smokes the cigar,

And he speaks of his daughter who drives a posh car.

[*Diddys (Romany; orig low slang) = Didikei, a gypsy of mixed marriage origins. *Scran (low slang) = scraps of food. *Greasy-heel, *Bog Spavine = ailments in horses. *Knacker-prices (from dialect) = prices paid for horses intended for slaughter. *Grais (Romany) = horses. *Chavvies (Romany) = boys. *Pani (Romany) = water (river). *Drom (Romany) = road]

The small town of Appleby in Cumbria has held an annual fair every June since permission was first granted in 1684 by James II for ‘a fair or market for the purchase and sale of all manner of goods, cattle, mares and geldings’. Nowadays it is solely for horses. It is officially a one-day affair, although it usually lasts a week and is claimed to be the largest gathering of Travellers in Britain. The fair is held on what was The Gallows Hill but is now known as Fair Hill. The layout of the town, built as it is on both sides of the River Eden, makes Appleby a convenient site for a horse-fair as can be seen by this picturesque description by a young Gypsy girl:

"When the little chavvies* get up, they take the grais* down the pani* and they wash the grais down, and then they ride the grais up and down the drom*."While this song is usually identified with English Travellers, it seems to be fairly popular among the Irish. We recorded it from three singers and we knew of several others who also sang it.

Ref: The Gypsies, Angus Fraser, The Peoples of Europe series, Blackwell, 1992

17 - Peter Thunderbolt (Roud 1453) Mary Delaney

‘Twas first in the month of April,

One morning by the dawn,

When there was byeslips and cowslips

Thrown all along the lawn.

Then the first of it, I kissed her roby* lips,

And laid her down on the grass;

And when she ‘turned to herself again,

It was then she cried, "Alas."

"Young man, if you’ve got your will of me,

Come quick and tell me your name,

And when my baby will be born

I will call it the same."

"For my name it is Peter Thunderbolt,

And the same I'll never deny,

And all my house and habitation

Lies by the Shannon side."

"Now fifty acres of great land,

My father, he can provide,

And I’ll put fifty more continue with it,

Down by the Shannon side."

Now it wasn’t six months after this,

One morning in the early spring,

When walking down on the flowery path,

My darling girl I spied,

And she was scarcely able to walk or talk,

Down by the Shannon side.

"Young man, if you're not going to marry me,

Come please tell me your name,

When this baby will be born

I will call it the same."

"I first told you, I was Peter Thunderbolt,

And my name I'll never deny,

And all of my house and habitation

Lies on the Shannon side."

An early text of this from a black-letter broadside entitled A Western Knight and dated 1629, was published in H E Rollins’ A Pepysian Garland. In his note to the song, the editor, compares it to The False Lover Won Back, (Child 63); Child Waters, (Child 218) and particularly to Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4).

Cecil Sharp collected several versions with the title The Shannon Side mainly from singers in Somerset, and Ord has it in his collection with the same title, where it is described as ‘an Irish folk-song common all over the North-east of Scotland’. William Christie, the Dean of Moray, quotes a verse in his Traditional Ballad Airs, but says: ‘The ballad of The Shannon Side is not suited for this work’.

It has also been found among English Gypsies, a recording of it being included on the Topic album, The Travelling Songster, sung by Phoebe Smith of Woodbridge, Suffolk. The only Irish versions we could find were one collected by Seamus Ennis for the BBC in the 1950s from Thomas Moran of Mohill, Co Leitrim and another we got from Pat McNamara of Kilshanny, Co Clare in 1976.

Ref: A Pepysian Garland, Hyder E Rollins (ed), Cambridge Univ Press, 1922; The Bothy Songs and Ballads (etc.), John Ord, Paisley, Alexander Gardner Ltd, 1930; Traditional Ballad Airs, W Christie, Edinburgh, David Douglas, 1881; The Travelling Songster, Topic LP T12 304.

Other CDs: Phoebe Smith - Topic TSCD 660.

18 - Going to Clonakilty the Other Day (Roud 16694) Mary Delaney

As I was going to Clonakilty the other day,

I hadn't got no trouble or delay.

Dan and Miley they were there

And Gerry Connors and his hair.

Singing ty yi yippee yippee yay.

Then I says, "Danny, Danny dear,

Come in to this old pub and we'll fix it here."

Dan and Miley they were there,

And Gerry Connors and his hair.

Singing ty yi yippee yippee yay.

I says, "Danny, don't you fret;![]()

The fiver is in me pocket yet,

For there's no need of bragging,

You were born in the wagon."

Singing ty yi yippee yippee yay.

One of the numerous pieces made up by Travellers concerning a small incident among themselves, maybe a dodgy horse deal or a drunken spree, the details of which are probably long forgotten, leaving only a handful of verses. Mikeen McCarthy also gave us a version of the same song with the following variation on the first verse:

I was going to Clonakilty the other day,

And who did I meet upon my way,

Oh the Driscolls I did meet

And my blood began to creep,

Singing ty yi yippee, yippee yay.

Both Mary and Mikeen had forgotten what the original incident was, or perhaps they never knew.

19 - Buried in Kilkenny (Roud 10, Child 12) Paddy Reilly

"Oh, what had you for your dinner now,

My own darling boy?

Oh, what had you for your dinner,

My comfort and my joy?"

"I had bread, beef and cold poison,

Mother, dress my bed soon,

I have a pain in my heart and

Wouldn’t I long to lie down."

"What will you leave your father now,

My own darling boy?

Oh, what will you leave your father,

My comfort and my joy?"

"I will leave him a coach and four horses,

Oh, mother dress my bed soon,

I have a pain in my heart and

Wouldn’t I long to lie down."

"What would you leave your mother now,

My own darling boy?

Oh, what would you leave your mother,

My comfort and my joy?"

"I will leave her the keys of all treasure,

Mother, dress my bed soon,

I have a pain in my heart and

Wouldn’t I long to lie down."

"What will you leave your children,

My own darling boy?

Oh, what will you leave your children,

My comfort and my joy?"

"Oh, they can follow their mother,

Oh, mother dress my bed soon,

I have a pain in my heart and

Wouldn’t I long to lie down."

"Where will you now be buried now,

My own darling boy?

Oh, where will you now be buried,

My comfort and my joy?"

"I will be buried in Kilkenny

Where I will take a long night’s sleep,

With a stone to my head

And a scraith* to my feet."

[* scraith = scraw, sod of turf - Irish]

Although popular in England, Scotland and America, the ballad of Lord Randal is not often found in Ireland except in fragmentary form or in the children’s version, Henry My Son. According to the collector, Tom Munnelly, it is more common among traditional singers in Irish than in English and is one of the few Child ballads to be found in the Irish language.

The handful of versions found in Ireland include an 11 verse set taken down by ballad scholar, Francis James Child, from the reciting of Ellen Healy ‘as repeated to her by a young girl in ‘Lackabairn, Co Kerry, who had heard it from a young girl around 1868. A version from Conchubhar Ó Cochláin, a labourer of Ballyvourney, Co Cork, in 1914, like Paddy’s, places the action of the ballad in Kilkenny:

"Where will you be buried, my own purtee boy,

Where will you be buried, my true loving joy?"

"In the church of Kilkenny and make my hole deep,

A stone at my head and a flag to my feet,

And lave me down easy and I’ll take a long sleep."

We also got it from fiddle player, storyteller and singer, Martin ‘Junior’ Crehan, a farmer from Co Clare in 1992.

Mary Delaney sang it to us the first time we met her, saying "You probably won’t like this one, it’s too old."

Ref: The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads, B H Bronson, Princeton Univ Press, 1959.

Other CDs: Mary Delaney - Topic TSCD 667; John MacDonald - Topic TSCD 653; Ray Driscoll - EFDSS CD 002; Frank Proffitt - Folk-Legacy CD1; George Spicer - MTCD 311-2; Jeannie Robertson, Thomas Moran, Elizabeth Cronin - Rounder CD 1775; Gordon Hall - Country Branch CBCD 095.

20 - Flowery Nolan (Roud 16693) Mikeen McCarthy

Oh he lived upon the *Stokestown Road,

Convening to *Arphin,

A man called Flowery Nolan,

A terror to all men,

He reached the age of seventy one,

He thought himself it was time,

For to go and get a missus,

His wedding 'twould be no crime.

Oh the news it quickly spread around

How Flowery wished to wed

Oh several maids came offer to him

And from them all he fled

Except one young fair maid,

Her fortune ‘twas rather high,

So he took and he married this young fair maid

To be his wedded wife.

Oh the wedding it lasted two nights and one day

'Til one night going in to bed,

Oh, Flowery turned all to his wife

And these are the words he said;

"You think you are my wedded wife

But I'll tell you you're not,

Oh you are only but my serving maid

And better is your lot."

"Oh there is two beds in my bedroom

And take the one to the right,

I've lived all alone for seventy one

And I'll lie alone tonight."

Oh when Mrs Nolan heard those words

She thought her husband queer,

Oh, packing up her belongings

From him she went away.

She tramped the road to her father's house,

'Tis there she did remain,

And then all the men in the Stokestown Road

Wouldn’t get her back again.

Now then, all ye pretty young fair maids,

A warning take by me,

Never marry an old man

Or sorry you will be,

Never marry an old man

‘Til you’re fed up of your life,

Or then you'll be coming home again

Like Flowery Nolan's wife.

Spoken: He was an old bachelor, he was… for years and he used be always talking about getting married, but it never… when 'twould be in his mind to get married, he'd never bother about it again, he said he'd wait 'til next year and next year and it goes on that way until he was seventy one year of age.

So bejay, that farmers around anyway, told him that 'twould be no harm to get a wife, to have someone to look after him like. So he advertised in the paper anyway, for the wife, so ‘twas more of a joke than anything else with all the lads around the parish of course, more blaggarding than anything else that time.

So bejay, a lot of the girls came around pulling his leg that time, letting on they were going to marry him and all that and bejay, this one meant it. Out of all her joking ‘tis she got the dirty turn out.

[* Stokestown: Strokestown, Co Roscommon; * Arphin: Elphin; Co Roscommon]

Arranged or ‘made’ marriages were very much an accepted part of rural life in Ireland up to comparatively recent times. In 1940, American researchers, Conrad M Arensberg and Solon T Kimball, stated that this form of marriage, known as matchmaking, was regarded as ‘the only respectable method of marriage and inheritance’.

The distribution of wealth and property was not the only reason for ‘made matches’ as they were called. Women from poor households which were unable to support the whole family would readily marry older farmers looking for a housekeeper, or maybe widowers with young children to care for.

Echoes of these arranged marriages are still to be found in Lisdoonvarna, Co Clare, where there is an annual matchmaking festival, although nowadays this is largely for the benefit of the tourists. This song seems to have survived only among Travellers.

Ref: Family and Community in Ireland, Arensberg and Kimball, Harvard Univ Press, 1940.

21 - Poor Old Man (Roud 2509) ‘Pop’s’ Johnny Connors

Three lines lilted.

"What brought you down from Kerry?" says the poor old man.

"Sure it’s the Connors’s is the blame and don’t the country know the same,

And look at them running down that lane," says the poor old man.

"Bad luck to you, young Gerry," says the poor old man.

"If you cook a stew* you don’t cook it near Ballaroo*

If you will, you’re bound sure rue," says the poor old man.

Three lines lilted.

"Oh, they were coming through Ross Town

And they had ponies big and brown,

And at me they did lick," says the poor old man.

"Bad luck to you, young Gerry," says the poor old man,

"I’ll run to take up my stick and I’ll got orders to drop it quick;

I’ll not, I’ll roar and squeal," says the poor old man.

"Bad luck to you, young Gerry," says the poor old man,

"But wasn’t I an unlucky whore, for to barricade my door?

Wasn’t I an unlucky whore?" says the poor old man.

[* Ballyroe, Co Kerry; * stew: great alarm, anxiety, excitement]

According to the singer, this song refers to a fight that took place in the town of New Ross, Co Wexford, sometime in the nineteen-thirties, between two travelling families, the Connors and Moorhouses. After a battle in the town, the Connors, coming off worst, fled and barricaded themselves in an abandoned cottage. The Moorhouses climbed on to the roof and brought the fight to a swift and bloody conclusion by tearing off the thatch and dropping down on their adversaries.

Other travellers have confirmed that the fight took place but they said that it was between two different branches of the Connors. Nobody is sure when the events took place although they thought it was over territory.

We were told: "The Waterford Connors was tinsmiths and the Wexford Connors didn’t want them coming into Wexford selling it."

One traveller referred to the incident as "The second Battle of Aughrim"! The song is a parody of An Sean Bhean Bhoct, (The Poor Old Woman).

22 - In Charlestown there Lived a Lass (Roud 1414) Mary Delaney

For in Charlestown there dwelled a lass,

She was as constant as she was true,

When the young man fell in courting her

And drew her in despair.

He courted her, oh, for six long months,

And to him she proved unkind,

Then he courted her for six long months,

And by him she proved a child.

"Oh, go home, go home to your dwelling place,

And don't bring your parients in disgrace.

Oh go home to your dwelling place

And you proved with a false young man."

"Now I will not go home to my dwelling place,

For to bring my parients in disgrace,

I would sooner go and drown myself

In a dark and a lonely place."

Now as Willie, he went out walking,

He went out to take fresh air,

And he seen his own love Mary

In the waves of the silvery tide.

Oh, he strips off his fine clothing,

To the river brim he swum,

And he brung his own love Mary

From the waves of the silvery tide.

"Oh Mary, darling Mary,

Is this what you have done,

And the last words I have said to you,

I just said it for fun."

Otherwise known as Floating Down the Tide; The Collier Lad; Molly and William etc.; this ballad was taken down several times in England: in Somerset, Oxfordshire, Suffolk and Dorset, and in Scotland, in Aberdeenshire. As far as we could find, there has been only one version made available from Ireland, that sung by publican Annie Mackenzie of Boho, Co Fermanagh, although the collector, Sean Corcoran, says it was widely known in that area.

The English texts locate the events as taking place in Camden, Brighton or Cambridge, while in Scotland it is set in Kilmarnock, Dumbarton or Marno (Marnock, Banffshire?). A Canadian version places the location as Charlottetown, similar to Mary’s Charlestown. One English version gives the unfaithful lover as a farmer’s son, while the three complete Scots texts make him a collier; otherwise he is, as here, ‘a false young man’.

Mary’s text has similarities to the two version of the song Camden Town, (Roud 564 Laws P18), recorded from English gypsies William Hughes and Nelson Ridley by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, particularly the verse that begins ‘Now I will not go home...’

Ref: Here is a Health (cassette), ed. Sean Corcoran, Arts Council of Northern Ireland 1986; Travellers Songs from England and Scotland, eds. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, R & K P, 1977.

Other CDs: Sarah Porter - MTCD 309-10; Ria Johnson - Helions Bumpstead NLCD 5.

Oh, there once been an old man who a long time was blind,

He reared one only daughter of a low degree.

And the first came to court her was a captain from sea,

He courted lovely Betsy by night and by day,

"For my life, gold or silver, I would give it all to thee,

If you tell me your father, my bonny Betsy."

Oh, the next came for to court her was a captain so grand,

He courted lovely Betsy by night and by day,

"For my life, gold or silver, wouldn’t I give it all to thee,

If you tell me your father, my bonny Betsy."

Oh, the next came for to court her was a squire so grand,

For he courted lovely Betsy by night and by day,

"For my life, gold or silver, wouldn’t I give it all to thee,

If you tell me your father, my bonny Betsy."

"For my father is an old man who a long time was blind,

His marks and his tokens to you I will give,

He was led by a dog, a chain and a bell."

"For roll on," says th’ould captain, "it is her I won’t take."

"Roll on," says th’ould merchant, "it is her I will forsake."

"Oh, roll on," says the squire, "and let all beggars agree,

Will you roll in my arms, my bonny Betsy?"

Oh, the squire he left down his ten thousand pound,

'Til he came to his farm, his tillage and his ground,

For the poor old blind beggar left down his ten thousand more.

The Rarest Ballad that Ever was Seen of the Blind Beggar of Bednall Green appeared as a broadside in 1672, was entered in the Stationers’ Register of London three years later and was still being sold as a street ballad in Ireland in the 1950s. Mikeen McCarthy named it as one of the songs he sold around the fairs and markets of Kerry up to that time.

According to Bishop Percy and the estimable John Timbs, this ballad was written during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603). In the Reliques of Ancient Poetry, Percy gives it in two parts, 67 verses in all, the story contained in the above coming at the end of part one. Timbs quotes 16 verses, most of them from Percy’s second part, which relates the uprising of the barons against Henry III and the death of their leader, Sir Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester in the battle of Evesham (1265). His son Henry: ‘Was felled by a blow he received in the fight, A blow that forever deprived him of sight’; and lay on the battlefield among the dead until found by ‘a baron’s faire daughter’. She carried him from the field, nursed him, married him and became the mother of ‘lovely Bessie’.

This explains the wealth of Bessie’s father, who adopted the disguise of a beggar to avoid discovery by his enemies.

The BBC recorded it in Co Leitrim in the 1950s and more recently it turned up in Inishowen, Co Donegal. It was popular among the Travellers we recorded; we heard it from four singers. We also got it from Martin Howley of Fanore, Co Clare.

When Mikeen McCarthy sang it for us he was camped just off Whitechapel Road, East London, within walking distance of The Blind Beggar public house, once notorious for its connections with the gangsters, Ronnie and Reggie Kray.

Ref: Reliques of Ancient Poetry, Thomas Percy, 1765; Abbeys, Castles and Ancient Halls of England and Wales, John Timbs, Frank Warne & Co (undated).

2 - Selling the Ballads (The Blind Beggar) Mikeen McCarthy

Well er, around where my father came from like, he was very well known as being a singer, not a singer now for his living like, but a fireside singer, we'll call it, and what we call céilidhing now, going to houses. Well they were very fond of that song where he came from, he'd be like the young people today singing, buying those records, you know. But it got that popular around that area, travelled from parish to parish then; where he got it from I do not know.

So when I used be selling the ballads then like, and my mother, they used ask me, "Have you any of your father's songs?", you know, when we went in to where we were reared now, "Have you the Blind Beggar?", and I used say, "No."

"Why don't you get those printed?", they'd say, "Those are the songs you'd sell, and if you get them printed I'll buy about a dozen of them off you next time I meet you."

So that's how I got them in print then myself. My father write them out for me and I'd go in to the printing office then, then I'd get them printed.

Well they were the songs that did sing, and many a time after I went into the pubs after selling ballads like and things like that and I'd hear all the lads inside on a fair day now, we’ll say markets and meetings, well when they'd have a few pints on them, 'tis then you'd hear my songs sung back again out of my ballads.

But I remember one day I was in Listowel Fair and I was selling ballads anyway. So I goes into a pub, I was fifteen years of age then - actually, I never wanted to pack it up, it was ashamed of the ladies I got, you know - but there was an American inside anyway, he wasn't back to Ireland I'd say for thirty years or something, he was saying.

So I sang that song now, The Blind Beggar, and he asked me to sing it again and every time I sang it he stuck a pound note into my top pocket.

He said, "Will you sing again?"

So I did, yeah. The pub was full all round like, what we call a nook now that time, a small bar, a private little bar off from the rest of the pub.

"And, will you sing it again?"

"I will; delighted" again, of course, another pound into my top pocket every time anyway. And the crowd was around, of course, and they were all throwing in two bobs apiece and a shilling apiece and I'd this pocket packed with silver money as well.

So he asked me, "Will you sing it for the last time."

Says I, "I'll keep singing it 'til morning if you want."

I'd six single pound notes in it when I came outside of the pub. I think I sold the rest of the ballads for half nothing to get away to the pictures".

The selling of printed song sheets, ‘ballads’, as they were known, was still very much a part of life right into the 1950s in rural Ireland. The trade at that time seemed to be fairly exclusively carried out by travellers who could be seen at the fairs and markets singing and selling them.