Article MT244

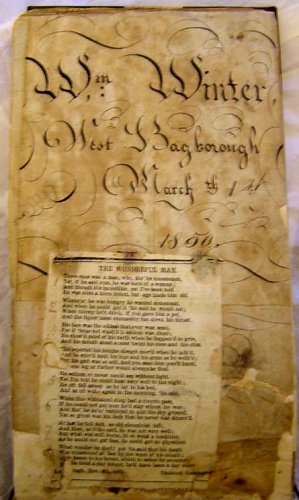

William Winter

Somerset village musician

His music in context

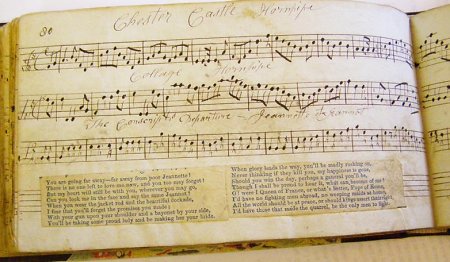

The manuscript compiled in 1848-1850 by fiddle player and shoemaker William Winter (1774-1861) has over 470 separate dance, song and other tunes. In 2007 Halsway Manor Society of Crowcombe, Somerset, published my edition of the manuscript as William Winter's Quantocks Tune Book. The book can be bought on-line at www.halswaymanor.co.uk

The manuscript compiled in 1848-1850 by fiddle player and shoemaker William Winter (1774-1861) has over 470 separate dance, song and other tunes. In 2007 Halsway Manor Society of Crowcombe, Somerset, published my edition of the manuscript as William Winter's Quantocks Tune Book. The book can be bought on-line at www.halswaymanor.co.uk

Halsway Manor's book has over 350 of these tunes. I have continued researching the origins of the tunes and the other items in the manuscript. I have been considering what place his music occupies in the history of popular and/or traditional music, and have also looked more closely at the song tunes.

This article expands on the introduction to the book as well as presentations I gave at the English Country Music Weekends at Bishops Castle and Whimple in 2007 and 2008.

The Musician and the MS:

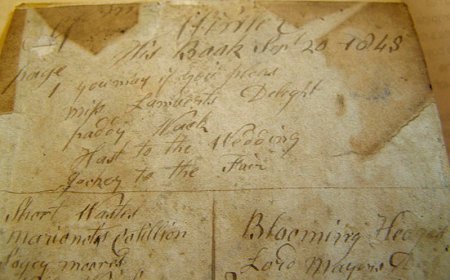

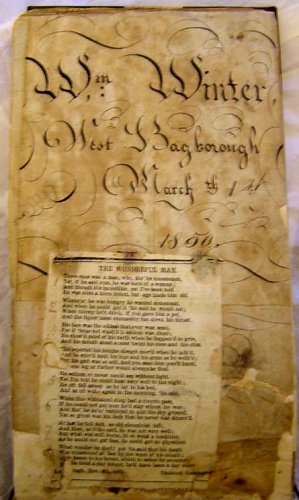

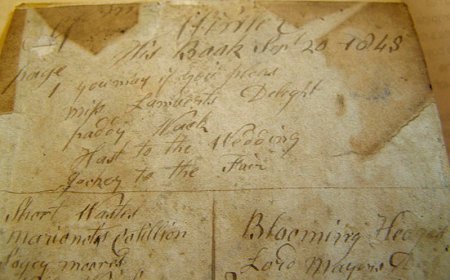

William Winter was born in 1774 in the village of Lydeard St Lawrence in Somerset where he played in the local church band in the first decade of the nineteenth century. He moved to West Bagborough in the Quantocks area in 1822. The manuscript, which is dated 1848 and 1850, is in two distinct parts. After it was found by librarian Geoff Rye in the early 1960s, both sections were bound together and placed in the library at Halsway Manor. The first short section is on narrower darker paper, and suggests that Winter transcribed these tunes at a different time, perhaps earlier in his life. There are two indices in the manuscript itself, and Winter may have transcribed his tunes at least twice during his life, perhaps when the 'originals' became unusable and then writing them out in a more readable fashion later. Some pages, probably from the earlier shorter section, are missing. Winter almost certainly noted the tunes over a period of more than 40 years from around 1810 until the 1850s.

William Winter was born in 1774 in the village of Lydeard St Lawrence in Somerset where he played in the local church band in the first decade of the nineteenth century. He moved to West Bagborough in the Quantocks area in 1822. The manuscript, which is dated 1848 and 1850, is in two distinct parts. After it was found by librarian Geoff Rye in the early 1960s, both sections were bound together and placed in the library at Halsway Manor. The first short section is on narrower darker paper, and suggests that Winter transcribed these tunes at a different time, perhaps earlier in his life. There are two indices in the manuscript itself, and Winter may have transcribed his tunes at least twice during his life, perhaps when the 'originals' became unusable and then writing them out in a more readable fashion later. Some pages, probably from the earlier shorter section, are missing. Winter almost certainly noted the tunes over a period of more than 40 years from around 1810 until the 1850s.

The Quantocks and Somerset in the early Victorian period:

In 1839 the population of West Bagborough was a mere 453, of whom only 25 were registered voters, suggesting that agricultural labourers and artisans made up the remainder. The local parish church of St Pancras was adjacent to Bagborough House where the owner was the Fenwick Bissett family. The nearest towns, Taunton and Bridgwater were over ten miles away by coach. The West Somerset railway line was built in nearby Bishops Lydeard in the mid 1850s.In Taunton in 1840 the local directory listed 3 music shops, 6 music teachers and 3 dancing masters. Some local villages also boasted music teachers, and there was a lively church music scene in the early 19th century with many having gallery bands and singers.

The Dance tunes:

The collection has over 400 dance tunes, including more than 150 jigs, 24 waltzes, 26 hornpipes, and more than 100 tunes in 2/4 and 4/4 time signatures. There are 27 marches, most of them named and probably of marching band or military origin. There are a few quadrille sets, some with familiar tunes, while others are contemporary compositions from the period.

Many of Winter's tunes, though by no means the majority, are familiar to us today from oral tradition, for example, Rose Tree, Brighton Camp, Dashing White Sergeant, Speed the Plough (in 4 versions) Go to the Devil and Shake yourself, Haste to the Wedding, and Bonnets so Blue.

Another batch of well-known tunes, Molbrook (Malbrook), Turnpike Gate, New Rigged Ship, Oh Susannah, The Campbells are Coming, The White Cockade, The Downfall of Paris, Duke of York's March, Scots Wha Hae, Off She Goes, are mentioned by street musicians interviewed by Henry Mayhew for his book London Labour and the London Poor. (1861, volume 3, from studies dating from the 1840s-50s) As Reg Hall has noted, some of them were in Scan Tester's repertoire. (I Never Played to many Posh Dances MT supplement no 2, p.79; article MT215)

Many more tunes, however, are not so well known today and come from a variety of sources both oral and written.

Winter's dance tune sources and his transcriptions:

Winter probably copied a large number of his dance tunes from 18th century printed collections, either directly or from other musicians' copies. Generally his script is skilful, bearing in mind that in the main part of the manuscript, he drew the stave lines and notation by hand, in pen and ink, in his seventies.

I have compared some of the tunes with, for example, the eighteenth century Thompson collections. 1 On pages numbered 29 to 30 in Winter's manuscript there is a sequence of six tunes which matches exactly that in Thompson's 5th collection of country dances published in 1787. These are The Pleasures of Salisbury, La Belle Chasse, The Sooner the Better, Miss Borolbey's Allemand, St Thomas's Day and Turk or No Turk .On pages 32-38 of the manuscript there is another sequence of tunes, all of them in the same order as in the equivalent Thompson volume. Winter probably spent many hours (by candlelight?) writing out these tunes. Inevitably, his transcriptions contain minor, and in some cases, important, errors. For one, small, example, in The Happy Fisherman (a jig in A major) the B part has a missing bar.

1 On pages numbered 29 to 30 in Winter's manuscript there is a sequence of six tunes which matches exactly that in Thompson's 5th collection of country dances published in 1787. These are The Pleasures of Salisbury, La Belle Chasse, The Sooner the Better, Miss Borolbey's Allemand, St Thomas's Day and Turk or No Turk .On pages 32-38 of the manuscript there is another sequence of tunes, all of them in the same order as in the equivalent Thompson volume. Winter probably spent many hours (by candlelight?) writing out these tunes. Inevitably, his transcriptions contain minor, and in some cases, important, errors. For one, small, example, in The Happy Fisherman (a jig in A major) the B part has a missing bar.

Apart from the large number of dance tunes from the eighteenth century, many of Winter's tunes were contemporary to his lifetime, from the theatre, 'popular' compositions and from minstrel shows. Tunes with a theatrical or classical origin include La Belle Jeanette, La Cachoucha, Dobney's Waltz, La Fille Sauvage, Oh tis Love, Ditanti Palpiti and The Duke of Reichstadt's Waltz.

Both Oh 'tis Love and Ditanti Palpiti appear with dance steps in Thomas Tegg's collection of dances Analysis of the London Ballroom published in 1825. Winter's local newspaper, the Taunton Courier, carried an advert for the music of Ditanti Palpiti, published by Clementi, in London. The paper carried regular adverts for sheet music, much of it classical, including a Beethoven piano sonata, also published by Clementi.La Cachoucha was originally a 3/8 Andalusian dance, popular in Cuba and used in a ballet at the Paris opera in 1936, danced by Fanny Essler. The sheet music became available in England in 1840. 2 Examples of minstrel tunes are Jim Crow, The Boatsman's Dance and Oh Susannah. Many Quadrille sets often used minstrel tunes and one of Winter's sets is marked 'Niger's [sic] quadrilles'. Other nineteenth century compositions include a small number of polkas, the Sturm Marsh Galop, the Zora Quadrille and the Grand Exhibition Waltz (written by R Linter, who also wrote Jenny Lind Polka). Most of the dance tunes in the manuscript are, nevertheless, of eighteenth century origin.

2 Examples of minstrel tunes are Jim Crow, The Boatsman's Dance and Oh Susannah. Many Quadrille sets often used minstrel tunes and one of Winter's sets is marked 'Niger's [sic] quadrilles'. Other nineteenth century compositions include a small number of polkas, the Sturm Marsh Galop, the Zora Quadrille and the Grand Exhibition Waltz (written by R Linter, who also wrote Jenny Lind Polka). Most of the dance tunes in the manuscript are, nevertheless, of eighteenth century origin.

Winter almost certainly had access to a variety of printed sources of music. Some tunes published in London in the magazine Musical Bijou can be found in the manuscript. We might guess that Winter also bought or had broadsides, but I could find no direct evidence of this. It is very likely, as he was a literate musician in a church band, that he also transcribed many tunes by ear. Tunes without titles, like two of the waltzes, a few hornpipes and quadrille tunes may be some of these.

How good are these tunes?

As others have noted in their reviews of the published book, some of the dance tunes may be safely left behind to 'history' but there are many gems in Winter's collection which are worth exploring. These include unusual versions of familiar favourites, for example Black Joak, Morgan Rattler, Captain White (Wike), Fisher's Hornpipe and The Triumph. But there are dozens of tunes, some from 18th century collections and a lesser number of 19th century origins, which, in my opinion, are as good as any in today's band repertoires. Just at random, I mention King Street Festino, The Pleasures of Salisbury, Breeches Loose, Trip to the Woodlands, Quicksteps in D (p.104) (jigs); The Cachoucha, Dobney's, and another (untitled) Waltz in A (p.61 of the manuscript); Pevensey Castle and Tourel's (hornpipes); and Royal Galop, Bristol and Mail Coach.

Are there any 'local' tunes?

I cannot identify any specific 'Somerset' dance tunes in the manuscript. It's possible that some of the untitled tunes were local, and no doubt, some of the tunes are 'local' versions of well known ones. Winter's collection shows just how well travelled was much of the dance tune repertoire of the day, either by oral route or by the circulation of sheet music.

The marches:

There are 27 marches in the manuscript, many of them with military titles, for example The Duke of York's Troops. Many of them are numbered in sequence, suggesting that they were used by bands for particular events. In 1814 Taunton saw a large procession and celebration of the victory over Napoleon, with a variety of bands. Other towns in Somerset had similar parades in which the whole population were encouraged to turn out. In Taunton, the parade was separated into particular trades, including shoemakers. One of the bands was a violin ensemble.

Local villages may also have had marching bands. One annual event was Oak Apple Day (May 29th), to celebrate the restoration of the monarchy on that day in 1660. Winter's March 9th has the words 'on May 29th' written after the title and may have been played at village Oak Apple Day events in the Quantocks, at Whitsuntide. These village events included a procession and bell ringing.

Performance practice. How were the tunes played?

As would be expected with material that came from sheet music, many of the dance tunes carry performance markings. It would be interesting to compare Winter's marks with those of the original published versions. Sometimes this is possible, as in the case of those from the Thompson collections. In other cases, it's not possible to tell whether Winter copied the marks exactly or with errors and inconsistencies. One example is the hornpipe Pevensey Castle. Bar 2 of the A part is:

But Bar 4, the same figure, reads:

Bar 2 of the B part reads:

Whereas Bar 4,the repeat, reads:

The first example is probably an inconsistency or error, whilst the second example shows bar 2 to be played legato with the dotted quavers, and its repeat is to be played staccato. Other hornpipes in the collection are notated without dotted quavers. A good number of Winter's tunes carry decorative grace notes, for example Bristol and Mail Coach, suggesting their 'baroque' origins. Others suggest rhythmic emphasis, for example, The Downfall of Paris, where a staccato quaver is followed by two legato semi quavers. Only a few of the tunes have any tempo markings, and these would have been from the original published sources. Nevertheless, playing for dancing carries a duty to play at an appropriate tempo. We will never know how William Winter played, but it's unlikely that he would have played every tune exactly as notated. Nor do we have to do this! Variation of particular detail in this music is inevitable and indeed, necessary!

Some of the more 'elegant' dances may have been played in a more 'refined' fashion that is the case today. We can only speculate how Winter's performance practice might have changed according to the context, but many of the tunes were likely to have been used at more 'gentlemanly' dances, whilst others may have been played at village events for the general community.

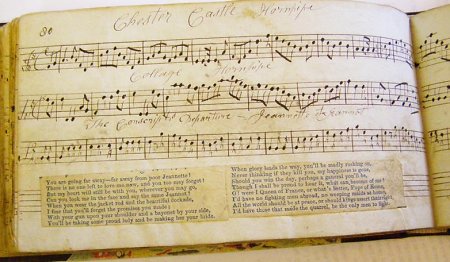

Song tunes in the manuscript:

William Winter's Quantock's Tune Book included one song from the manuscript, The Conscripts Departure, with lyrics that were originally from a newspaper cutting. Only two other song tunes in the manuscript included words (Why Don't the men propose and Parson Brown's Sheep)

William Winter's Quantock's Tune Book included one song from the manuscript, The Conscripts Departure, with lyrics that were originally from a newspaper cutting. Only two other song tunes in the manuscript included words (Why Don't the men propose and Parson Brown's Sheep)

Most of the song tunes here did not retain their popularity. I am including this information because it helps to give a more complete picture of Winter's music, as well as of the tastes of the community in this part of the West Country. Many of the song tunes can be categorised as the 'light classical' of the time, for the entertainment of the professional class. Nevertheless, some of them may have been attractive to the local artisans and labourers.

Two of the songs (How sweet in the Woodlands and Sweet doth blush the rosy morning) have texts by Dr Henry Harington of Bath. (1727-1826). He was a physician to the Duke of York, a local politician and mayor and was an amateur musician who composed glees and part songs, many of them humorous. Two collections of his songs can be found in Bath Reference Library.

Bath poet Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797-1839) was more well-known. Winter's manuscript has seven songs with his texts. They include Isle of Beauty and Home Sweet Home. Two of his more humorous, ironic songs are: Oh no we never mention her and Why don't the men propose, mamma?

Oh no… was clearly a popular song for many years after it was published around 1830. In Dickens, The Uncommon Traveller, it is referenced in his character, 'Mrs Onowenever' The first stanza of the song is:

Oh no we never mention her Her name is never heard

My lips are now forbid to speak That once familiar word

From sport to sport they hurry me To banish my regret

And when they win a smile from me They think that I forget

The complete song can be found in The Songs of England edited by J L Hatton and published by Boosey in London in 1882 (p144).

There is insufficient space here for the full text of Why don't the men propose, mamma, but here is a taster:

Why don't the men propose?

Why don't the men propose?

Each seems just coming to the point

And then away he goes

It is no fault of yours mamma that everybody know

You fete the finest men in town

Yet O they won't propose

It was published as a poem in The Young Lady's Book of Elegant Poetry by De Silver Thomas and Co of Philadelphia USA in 1836 (available to read at Google Books). William Winter's manuscript has several verses in his rather illegible handwriting. In his version the unfortunate woman is ten years older at 41!

Popular tunes associated with Robert Burns' verses can be found in the manuscript. As well as Auld Lang Syne and Scots Wha Hae there are five others including Green Grow the Rushes and Robin Adair (written by Winter as Robing a Dore)

Other song tunes in the manuscript are of varied genres, for example:

- Away with Melancholy which originated in Mozart's opera The Magic Flute

- Believe me if all those endearing young charms - the tune of which became common in oral tradition. It was published in the early 19th century in Moore's Merry Melodies, a common source of popular song of the period.

- Breathe Soft ye winds, a glee by William Paxton. Other glees and part-song tunes in the manuscript include Come all ye boys that fear no noise, Jolly Lasses, Lets Live and Lets Love, and Hark the Bonny Christ Church Bells (by Rev Aldrich of Oxford). Alfred Williams collected a version of Hark the Bonny … in Quenington, Gloucestershire.

- The Conscript's Departure This has appeared in many guises in the English speaking diaspora. It found its way to oral tradition and was collected by Alfred Williams.

Popular and 'parlour' song tunes in the manuscript include:

- Darby Kelly O, Drink to me Only, Hearts of Oak, The Honest Yorkshire Man, Life Let Us Cherish, We Have lived and loved together, Woodman Spare that tree (which was written by Henry Russell, composer of A Life on the Ocean Wave, a tune which is in one of Winter's quadrille sets)

- Two nineteenth century song tunes are The Last Melody of Pestal, which was published in1845 about a Polish martyr who was one of the Decembrists in the 1825 uprising against the Tsar of Russia, and Down Where the Bluebells Grow, a song written by G A Lee, published in 1841.

- The song Mary Blane was in the repertoire of the Ethopian Serenaders who appeared in many forms and toured the West Country in 1859. It was part of the early minstrel acts in the 1830s. Mayhew's work on street musicians refers to the song as part of a theatrical routine, and it also appeared on a broadside.

- An indication of the audiences for some of these songs is given in the British Library catalogue entry for In My Cottage near a Wood (on page 69 of the Winter manuscript). It was published by Longman in London in 1815 and 'written by Mr R A Moreland as sung at the Nobility and Gentry's concerts'.

The manuscript also has a few Scots Irish and Welsh airs, for example:

- Kelvin Grove, Poor Mary Ann (All through the night), Sweet Jessie (the Flower of Dunblane) and Who'st Weeping Winifred

An item which was probably available on a broadsheet in Winter's day is Parson Brown's Sheep. The text and the tune are in the manuscript as shown here.

Parson Brown's Sheep

Not long ago in our town

A little place of great renown

There lived a man named Mr Brown

And he was our parson

Father he was very poor

Christmas it was very near

We'd neither mutton beef nor beer

For our Christmas dinner

They were very hard times for poor father. Faider had lost his work cause he was getting ould and couldnt do much.

So I went to Parson Brown and asked him for some vittles but he wouldn't gi me any, but he said the dog ate one and sent me back broken hearted.

When I came back who should there be but faider wi one of Parson Brown's fat weather sheep. He said that's the first time I ever robbed in my life.

But they wouldn't let me work, and I cannot starve. Egad!

I was natural pleased to see the old sheep and all, and ran up and down singing.

Faider stole the Parson's sheep

And we shall have both pudding and meat

And a Merry Christmas we shall keep

But I mayn't say naught about it

Sang up and down the street all day

Parson heard what I did say

[manuscript unclear here]

Say he will give the [e] half a crown

A suit of clothes and money down

If to church you'll go along

And sing it to the people

I said I'm danged if I cant, mother, and 'Well, she said, do lad, but dont thee say a word about the old sheep. If thee do they'll hang thee and thy father too'.

No, I said I wont then, so off I went in my bran new clothes.

I'm sure I never looked as a cat with a new pepper box [manuscript unclear here].

I goes clink a me clank, clink a me clank right up to the Parson, he began to tell the folk what I had come for.

'Now' he says 'I hope you'll harken attentively to what this lad are about to sing for it is a most notorious and outrageous crime as ever was committed and ought to be severely punished and every word he says is as true as the Gospel I am preaching .

Now then he swelled himself up as big as a turkey cock, blew his nose and told me to begin, Then I begin to, singing,

As I was in the field one day

I saw our parson very gay

Romping Molly in the hay

And turned her upside down Sir

And for fear I shouldn't be known

A suit of clothes and half a crown

Verily given me by Mr Brown

For I to come and tell you

He He He ... I thought parson went romping mad. He stamped and swore it was the biggest lie that ever was told. But folks wouldn't believe him. They all ran out of church and cried, shame on Parson. He sent a big crook at me but hit an old lady on the head. Down she went and Parson plump on top of her. I ran off singing,

I have done old Parson Brown

Of a suit of clothes and half a crown

For telling all the folks around

What he had done to Molly

Musical influences:

Winter's manuscript is fascinating because it shows the variety of musical influences that found their way into rural Somerset from the late 18th to the mid 19th centuries.

American influence (apart from the minstrels) can be seen with Life on the Ocean Wave, written by H Russell and used in a quadrille tune set. Tunes like Logier's March show the influence of 'popular' classical music. Handel's Harmonious Blacksmith and Verdi's Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves from his opera Nabucco are also from the classical genre (though Winter's notation is only an approximation!)

Winter therefore is in line with many more recent 'traditional' musicians in that amongst the wealth of English dance music, we find tunes from overseas, and from other genres. The increasingly widespread distribution of sheet music is probably responsible for this.

Bearing in mind Winter's church band, it is perhaps surprising that there are only two hymn tunes in the manuscript. Winter's hymns are marked '11', which is Mount Pleasant (by West gallery composer James Leach)(1762-1798) and '288' which is Acton.

William Winter: Community Musician:

We know from churchwarden's accounts at Lydeard St Lawrence that Winter played in the local parish church band in the first ten years of the 19th century. Other band musicians played oboe and viol.

We know from churchwarden's accounts at Lydeard St Lawrence that Winter played in the local parish church band in the first ten years of the 19th century. Other band musicians played oboe and viol.

It would interesting to compare Winter's musical life with that of another fiddle playing shoemaker - Michael Turner of Sussex. Winter's manuscript is almost exactly contemporary with Turner's and comparison of the tune titles in the two collections is interesting. At least eight of the dance tunes are familiar favourites common to both manuscripts. Turner's list, however, has a larger proportion of 'new' quadrilles, polkas and waltzes.

Vic Gammon's MT article MT068 includes a biographical card on Turner, which says of him:

'He was in great demand at village fetes… and at the big houses to play the music at their dances; and between times he would perform a first rate jig playing his fiddle….or sing a capital comic song.'

Just like William Winter? Unfortunately, we have no similar written account of Winter's performances. Apart from local diaries such as those of the Reverend William Holland of Overstowey (Paupers and Pig Killers) 3 there is little written material recording informal musical events in the Quantocks in the early 19th century.

3 there is little written material recording informal musical events in the Quantocks in the early 19th century.

The large number of dance tunes in Winter's manuscript suggests he played for village dances, and at local social events like harvest festivals. According to contemporary newspaper reports, in some parts of the county harvest festivals involved cider and dancing. In other villages, they were more sedate. It's likely, judging by the varied nature of the dance and song tunes in the manuscript, that Winter played for more formal events as well as those for all the community. Unlike Scan Tester, he probably did play for 'posh' dances, and the presence of 'parlour' songs might confirm this, though Parson Brown's Sheep would have appealed to the agricultural labourers. The Taunton Courier newspaper carried regular reports of dancing in the town for local 'society' and advertised newly published dances. My impression from these reports is that social life amongst the 'leisured' classes in Somerset towns mirrored that in Bath. Dancing classes were often advertised during the daytime hours.

Around 60 years after Winter's manuscript, Cecil Sharp noted many fine tunes from the East Somerset area close to the Mendip Hills, from, for example, James Higgins in Shepton Mallet, Henry and Thomas Cave in Midsomer Norton and Francis Trusler in Mells. With one or two exceptions like The Triumph and Bonnets so Blue, there are no tunes common with the Winter manuscript. It might indicate a clear difference in repertoire between literate and oral traditions in the same region. Perhaps the oral tradition is and was more 'distilled' in that many tunes in Winter's collection may not have been played very often; others not at all.

The evidence from church accounts and from his own manuscript is therefore that William Winter, as a shoemaker and fiddle player, served the local community, from the farm labourer to the parish church and landowners. His collection dates from an age when the concept of 'popular' music was different; instead of recordings, any 'commercial' aspect related to sheet music. Winter's collection is an example of the variety of community music of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when perhaps the distinction between 'popular' and 'art' music was not so clear. His influences were as 'exotic' (minstrel, European dance) as they were English.

A useful source of tunes:

When I was researching material for the booklet for the Ray Andrews CD (MTCD314) I found a list of tunes (including song tunes) in his banjo case. Alongside his stack of sheet music and magazines, the list was a reminder of his repertoire for gigs in the Bristol community. Winter's 470+ tunes were his 'reminder' of what to select for a particular occasion. We have the opportunity to do likewise. There is plenty of material here to choose from.

Acknowledgements:

The text of Parson Brown's Sheep and musical extracts are used with the permission of Halsway Manor Society. More detailed information about all the tunes and songs in the Winter manuscript can be found at www.halswaymanor.co.uk

John Shaw for the information on the two hymn tunes.

Somerset Studies library, Taunton Central Library, for information from the Taunton Courier . Somerset Record Office, for information from the church accounts for Lydeard St Lawrence.

Other sources have not been noted in detail and include the British Library catalogue and web sites where referred to in the text.

Footnotes:

1. Four volumes of Thompson have been transcribed by Fynn Titford-Mock and can be seen on the Village Music Project web site; copies of the originals are in the Vaughan Williams library at Cecil Sharp House.

2. Information from the Dolmetsch Historical Dance Society.

3. Paupers and Pig Killers The Diary of William Holland A Somerset Parson 1799-1818, Sutton. Ayres, Jack (ed) 1984 ISBN 0862990521.

Geoff Woolfe - 14.5.10

Article MT244

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 19.5.10

The manuscript compiled in 1848-1850 by fiddle player and shoemaker William Winter (1774-1861) has over 470 separate dance, song and other tunes. In 2007 Halsway Manor Society of Crowcombe, Somerset, published my edition of the manuscript as William Winter's Quantocks Tune Book. The book can be bought on-line at www.halswaymanor.co.uk

The manuscript compiled in 1848-1850 by fiddle player and shoemaker William Winter (1774-1861) has over 470 separate dance, song and other tunes. In 2007 Halsway Manor Society of Crowcombe, Somerset, published my edition of the manuscript as William Winter's Quantocks Tune Book. The book can be bought on-line at www.halswaymanor.co.uk

William Winter was born in 1774 in the village of Lydeard St Lawrence in Somerset where he played in the local church band in the first decade of the nineteenth century. He moved to West Bagborough in the Quantocks area in 1822. The manuscript, which is dated 1848 and 1850, is in two distinct parts. After it was found by librarian Geoff Rye in the early 1960s, both sections were bound together and placed in the library at Halsway Manor. The first short section is on narrower darker paper, and suggests that Winter transcribed these tunes at a different time, perhaps earlier in his life. There are two indices in the manuscript itself, and Winter may have transcribed his tunes at least twice during his life, perhaps when the 'originals' became unusable and then writing them out in a more readable fashion later. Some pages, probably from the earlier shorter section, are missing. Winter almost certainly noted the tunes over a period of more than 40 years from around 1810 until the 1850s.

William Winter was born in 1774 in the village of Lydeard St Lawrence in Somerset where he played in the local church band in the first decade of the nineteenth century. He moved to West Bagborough in the Quantocks area in 1822. The manuscript, which is dated 1848 and 1850, is in two distinct parts. After it was found by librarian Geoff Rye in the early 1960s, both sections were bound together and placed in the library at Halsway Manor. The first short section is on narrower darker paper, and suggests that Winter transcribed these tunes at a different time, perhaps earlier in his life. There are two indices in the manuscript itself, and Winter may have transcribed his tunes at least twice during his life, perhaps when the 'originals' became unusable and then writing them out in a more readable fashion later. Some pages, probably from the earlier shorter section, are missing. Winter almost certainly noted the tunes over a period of more than 40 years from around 1810 until the 1850s.

William Winter's Quantock's Tune Book included one song from the manuscript, The Conscripts Departure, with lyrics that were originally from a newspaper cutting. Only two other song tunes in the manuscript included words (Why Don't the men propose and Parson Brown's Sheep)

William Winter's Quantock's Tune Book included one song from the manuscript, The Conscripts Departure, with lyrics that were originally from a newspaper cutting. Only two other song tunes in the manuscript included words (Why Don't the men propose and Parson Brown's Sheep)

We know from churchwarden's accounts at Lydeard St Lawrence that Winter played in the local parish church band in the first ten years of the 19th century. Other band musicians played oboe and viol.

We know from churchwarden's accounts at Lydeard St Lawrence that Winter played in the local parish church band in the first ten years of the 19th century. Other band musicians played oboe and viol.