Blues From the Pit 1927-1942

Old Hat Records CD-1008

1. Down At Jasper's Bar-B-Que - Frankie 'Half Pint' Jaxon; 2. Who Did You Give My Barbecue To? Part 1 - 'Big Boy' Teddy Edwards; 3. Pig Meat on the Line - Memphis Minnie; 4. Pork Chop Blues - The Two Charlies; 5. Barbecue Bust - Mississippi Jook Band; 6. I Crave My Pig Meat - Blind Boy Fuller; 7. Barbecue Blues - Barbecue Bob; 8. Pepper Sauce Mama - Charlie Campbell and His Red Peppers; 9. Pigmeat Blues - Georgia White; 10. Gimme a Pig's Foot and a Bottle of Beer - Frankie 'Half Pint' Jaxon; 11. Pigs' Feet and Slaw - Tiny Parham and his Musicians12. Ham Bone am Sweet - The Four Southern Singers; 13. Meat Cuttin' Blues - Hunter and Jenkins; 14. Barbecue Any Old Time - Brownie Mcghee; 15. Come On Down - Jolly Two; 16. Barbecue Bess - Bessie Jackson; 17. I Heard the Voice of a Pork Chop - Bogus Ben Covington; 18. Pig Meat Is What I Crave - Bo Carter; 19. Fat Meat Is Good Meat - Savannah Churchill and her All Star Seven; 20. Smoked Meat Blues - Richard M Jones' Jazz Wizards; 21. Meat Man Pete (Pete, The Dealer In Meat) - Vance Dixon and his Pencils; 22. Barbecue Blues - Hank Jones and his Ginger; 23. Who Did You Give My Barbecue To? Part 2 - 'Big Boy' Teddy Edwards; 24. Alabama Barbecue - Tempo King and his Kings of Tempo.

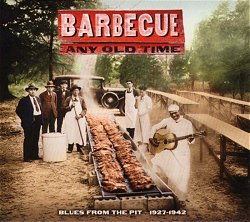

The last thematic CD that I reviewed for this website focussed on the subject of murder, so one about barbecue makes for a pleasant change, although vegetarian readers may beg to differ. This compilation has the usual virtues of an Old Hat release: first rate sound; evocative photographs, most of them archival; full discographical data; and extensive notes, on the songs by producer Marshall Wyatt, and on the history and sociology of barbecue by historian Tom Hanchett.

The last thematic CD that I reviewed for this website focussed on the subject of murder, so one about barbecue makes for a pleasant change, although vegetarian readers may beg to differ. This compilation has the usual virtues of an Old Hat release: first rate sound; evocative photographs, most of them archival; full discographical data; and extensive notes, on the songs by producer Marshall Wyatt, and on the history and sociology of barbecue by historian Tom Hanchett.

In the bonus footage accompanying David Simon's series Tremé on DVD, Kermit Ruffins proudly displays a formidable barbecue oven on wheels, and describes himself as "a barbecue cook who plays trumpet on the side." It's no coincidence that his band are called the Barbecue Swingsters, and in the same way that barbecue, as both food and cooking technique, is an important part of Ruffins' self-definition, its also a cherished marker of Southern identity.

Barbecues basic method is the cooking of meat over wood and charcoal, often burned in a pit dug in the ground, but the process is subject to many local variations, beginning with the dead animal selected for the purpose: 'beef brisket in Texas, mutton in Kentucky, and pork most everywhere else, prepared in your homeplaces special tradition', writes Hanchett, surprisingly making no mention of the goat which was Mississippi fife player Othar Turner's speciality. Mixes of herbs, spices and other flavourings are also subject to much regional variation: the vinegar-and-tomato of North Carolina is said to reflect German heritage, and the dry rubs that make Payne's the most delicious commercial barbecue in Memphis are apparently influenced by Greek methods.

As the Great Migration carried Southerners, both white and black, across the country, they took barbecue with them, and Hanchett suggests that barbecue became a marker of prosperity in their new urban environments, and that 'these are boasting songs, similar in a way to modern hip-hop music … On these old records, barbecue stands in for all that is good: money in your pocket, someone eager for your sexual charms. Oh, and lots of fine food whenever you want it.'

This is an argument that carries some weight: Hanchett is surely right that the barbecue restaurants that 'began popping up in American cities during the 1910s-1920s … emphasized a down-home vibe but were actually temples of newness': we can hear the evidence when Frankie Jaxon celebrates the pleasures of city life on offer at Jasper's Bar-B-Que, in which he includes radio and the newfangled jukebox, both dependent on electricity for their operation; and Bessie Jackson (real name Lucille Bogan) sounds wholly accustomed to, and confident within, an urban setting where the barbecue that she offers for sale is transparently a synonym - euphemism would be entirely the wrong word here - for sex. Jaxon's other number, Gimme a Pigs Foot and a Bottle of Beer, much better known in Bessie Smith's version, also takes place in the distinctively urban setting of a rent party.

For the most part, though, I find Hanchetts suggestion more ingenious than convincing. More often, I hear barbecue - when it actually is barbecue, which is a point well come back to - being referenced as a nostalgic reminder of down-home folks and folkways in the new and challenging urban setting. Its also worth remembering that the movement from countryside to towns and cities took place within, as well as away from, the South; consider, for instance, the Jolly Two (Sonny Scott and Walter Roland), inviting listeners to

Indeed, the idea of barbecue as a signifier of modernity is undermined by the number of recordings included here which either continue or revive the tropes of minstrelsy. Banjo and rack harmonica player Bogus Ben Covington ('bogus' because he used to busk while pretending to be blind) sings a song that peddles chicken-stealing stereotypes; elements of I Heard the Voice of a Pork Chop are also incorporated into the Two Charlies song, which recommends a pork chop, Polish [sausage], and some pork and beans as the remedy for both stomach trouble from missing my meals (possible) and diabetes (highly inadvisable.)

Im aware, of course, that songs like these functioned on more than one level, allowing white audiences to confirm stereotypes of black greed and dishonesty, while simultaneously mocking those images for black listeners, and making humour out of the realities of hunger and poverty. Nevertheless, there cant be much doubt that the Four Southern Singers, reviving Watermelon on the Vine, are offering a nostalgic vision of plantation life for the comfort of white romantic racists. Confirmation comes from their other recorded repertoire, and from their radio publicity photos, in which they appear as a ragged-trousered field hand, a handkerchief-headed washerwoman, and a couple of Uncle Toms (or perhaps Uncle Remuses). That they combine these visual and verbal images with swinging and varied musical accompaniments, which include some modernistic Mills Brothers-type instrumental imitations, just goes to show that nothing is straightforward.

As do Tempo King and His Kings of Tempo. Between them, the singer (who may - though nothing definite is known - be drummer Stan King, who set the tempo) and his pianist, Queenie Ada Rubin, manage a pretty good Fats Waller imitation (on Bluebird, the budget label of RCA Victor, for whom the real Fats was recording!); but the Kings of Tempo were certainly white, and Tempo King probably was. Alabama Barbecue, for all its undeniable verve and charm, is another exoticist venture into a reality-based, but ultimately imaginary, black world, a song from the same stable as Johnny Mercer's similarly cod-revivalist Accentuate the Positive.

It seems, then that barbecue functions fairly often as a signifier of Southlands, both real and imaginary, and occasionally as 'exhibit A' in celebrations of city living. What seems to be in no doubt, however, is that most blues which are nominally about barbecued meat are actually about sex: by my count, roughly half of the CD's 24 tracks go down that road. It's interesting that 'pig meat', which appears in the titles of songs by Memphis Minnie, Blind Boy Fuller, Georgia White and Bo Carter (and as 'fat meat' in Savannah Churchill's) is used by both sexes as a term for the pleasures of the flesh; on this CD, they seem always have heterosexual contexts in mind.

This is the place to note that songs like Meat Cuttin Blues and Meat Man Pete, both of which supposedly eulogise the skills of a butcher with his meat, are actually one degree further distant from the cooked meat produced by a barbecue pit. As for the three instrumentals (by the Mississippi Juke Band, Tiny Parham, and Hank Jones and His Ginger), we can only take it on trust that the musicians, rather than the record companies, supplied the titles. Robert Hicks was nicknamed Barbecue Bob because he worked at an Atlanta barbecue pit as all three of Louis Jordan's 'a cook and a waiter and a good musician' (Saturday Night Fish Fry); but his Barbecue Blues is so named because it was his signature blues, and because he was proud of it - rightly so; its a simply wonderful performance. The lyrics make no reference whatever to barbecue, however, although the advertising cannily did, incidentally showing how good barbecue was seen as a metaphor of down-home authenticity: 'These blues are cooked to a turn. Anybody who likes the real thing in blues is in for a feast this time. Accompanied by his guitar, Bob adds plenty of vocal seasoning to this record.' Amen to that.

It will be obvious that I have some problems with the misfit between the music on this CD and the theoretical presentation of it. However, I have very little cause for complaint about its quality, considered simply as music. One endures Papa Too Sweet's stentorian sprechgesang for the reward of Vance Dixon's clarinet solo, and Frankie Jaxon sounds tired on Gimme a Pigs Foot; but his other song is the perfect opening track: you can almost see him capering about the stage of Chicago's Apollo Theater. Everything else here is a choice cut from the carcass of the blues, and as I noted at the start of this review, the presentation is exemplary. If music be the food of love, as Shakespeare suggested, this CD demonstrates that it can also be both the love of food and food for thought. Kudos to Old Hat for compiling and issuing Barbecue Any Old Time, and can we have a collection of blues about fish and fishing next, please?

Chris Smith - 12.10.11

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |