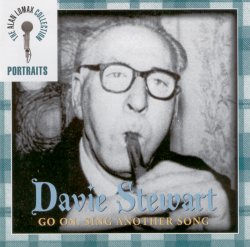

Davie Stewart

Go On, Sing Another Song

Alan Lomax Collection: Portraits Series

Rounder CD1833

The Tarves Rant* (6.06), The Hash o' Bennagoak* (2.47), Last Nicht I Was in the Granzie* (2.47), Onything at all for a few Coppers* (Interview) (4.39), Mormond Braes (3.34), Go On, Sing Another Song* (Interview) (2.06), Tramps and Hawkers (5.49), A Wagon of Their Own, Maybe Three or Four Ponies* (Interview)(3.06), Mcginty's Meal and Ale* (4.54), The First Song that I Ever Learned* (Interview) (1.29) Macpherson's Rant (6.44), Auld Jock Bruce oí The Fornet (3.26), Nicky Tams*(2.58), The Highland Tinker* (1.38), Maggie the Milkmaid* (2.48), The Dying Ploughboy* (4.02), Jamie Raeburn* (4.30), Bing Avree, Dilly* (Interview) (1.44), The Dowie Dens of Yarrow (6:26)

* Previously unreleased.

In reviewing Davieís previous Topic/Greentrax album on this site, I attempted a short biography of Davieís life. Rather than repeat it here, readers may want to follow that link before reading this.  The biography was assembled from the small number of articles and interviews with Davie that I was able to access plus some stories I had heard Davie himself tell; mostly these were written/conducted by Hamish Henderson. The information led me to state that 'Davie Stewart was born in 1901, the son and grandson of two Robert Stewarts, both travelling tinsmiths and hawkers, in the Buchan area, nobody seems to be exactly sure where'. Well, I did not have access to these Alan Lomax interviews when I wrote that. Here Davie dispels any romantic mystery surrounding his birth:

The biography was assembled from the small number of articles and interviews with Davie that I was able to access plus some stories I had heard Davie himself tell; mostly these were written/conducted by Hamish Henderson. The information led me to state that 'Davie Stewart was born in 1901, the son and grandson of two Robert Stewarts, both travelling tinsmiths and hawkers, in the Buchan area, nobody seems to be exactly sure where'. Well, I did not have access to these Alan Lomax interviews when I wrote that. Here Davie dispels any romantic mystery surrounding his birth:

Davie Stewart: I was born in the place called Peterhead in Aberdeenshire. 1901 And, eh, a place in Aberdeenshire. Peterhead. in, eh, in, eh, a place called Windmill Street. Peterhead. And my father was, eh, he did everything. He hawked, he made tin. He played the pipes for a liviní. But mostly' hawkin' round the country with a horse and cart. Ma mother also. She went hawkiní, too. And eh. Of course, eh, her father, ma mother's father was come of the Irish and her own name was McGuire, and, eh, my father, he was, eh, Scotch. He was born in Aberdeenshire, at a place called the Guavels, thatís about twelve or fourteen miles from Aberdeen. Well, when ah was a wee boy ah remember the days when ah used to go with my bare feet, begging sometimes to farmhouses and getting some potatoes and milk and bread and what you call oatcakes in Scotland. Sometimes, eh, I'd get a shot at the practice chanter myself, and learn to play wee bits of tunes, then as I grew up, went away mostly on my own on the road. I went to school in Aberdeen - ah started the age of four year old. And I left school. I didnít go back because there was no much restrictions in them days in schools. So I went away, mostly with other boys older than myself, cousins of mines - I've often been alone with a cousin of mine called Bliní Robin. He lives in Aberdeen noo: He's an old man. he's a blind man. He was a good piper and I used often to go along with him to fairs and markets and I used to lead him round. And ah learned mostly all my songs off of him. And, eh, ...

Alan Lomax: What was he like?

Stewart: Well. Heís a, he'd be a man' about - he'd be about seventy now, stout man. Blind, used to wear the kilt, play the bagpipes, and then if he wasn't playing pipes he was away out gatherin rags and trying to make a livin' some way.

Now, as Ah grew older ah went away on my own. Hawkiní, sellin' writin' pads, going to what you call the moss of Scotland and gettin' some heather and makin' scrubbers for pots and makin' besoms for floors for sweepin' out - what you call brooms. I've often made, eh, artificial flowers and still today, to the present day, I make artificial flowers very well. And I can play the pipes, whistle, accordion, sing, tell stories - lots of different things. Well, as being a tinker or a Traveller on the road. I can mostly go to any farmhouse or any place - never be stuck. Sing a song - anything at all for a few coppers. So, at the present moment ah live in Dundee - more settled down now as ah get older. I'll be fifty-seven on the first day of April coming now and ah've spent some useful days on the road. Happy.

Throughout the interviews Davie sounds confident, articulate and in no way in awe of the famous American who was asking him questions; miles away, in fact, from the "galoot" that was his by-name and to a certain extent his public persona. It must be remembered that Davie was almost totally illiterate; I remember being very embarrassed when I asked him to write his name and address for me and he had to explain that he couldnít. Yet the summary of his life that Davie gives has quite a literary flavour to it.

Throughout the interviews Davie sounds confident, articulate and in no way in awe of the famous American who was asking him questions; miles away, in fact, from the "galoot" that was his by-name and to a certain extent his public persona. It must be remembered that Davie was almost totally illiterate; I remember being very embarrassed when I asked him to write his name and address for me and he had to explain that he couldnít. Yet the summary of his life that Davie gives has quite a literary flavour to it.

The above extract also strikes a particular chord with me in the "missed opportunities" department. I met a very old Blin' Robin at a party in Fetterangus around 1971. I had heard his name mentioned as a singer of note amongst Scots travellers and I did manage to have a few words with him. However, the party was to celebrate the release of one of the ífriensí of the Fetterangus travellers from Peterhead jail that morning and heavy drinking with no music was the order of the day. If I had known that he was the main source of Davieís songs, I would have delayed my impending departure the following morning to visit him in his cottage that was just across the road. (Was Blin' Robin, I think his surname was Hutchison, ever recorded, does anybody out there know?)

Many other insights are offered by the five sections of interview, two of which I would like to pick up here. First of all, Davie talking about his sixteen years - from 1932 - that he spent in Ireland:

Davie Stewart: I learnt a lot of Irish music and a good few Irish songs. And I think Irish songs is very good and I like Irish music very well, especially the uilleann pipes or a fiddle, or the guitar and banjo - mostly the pipes and the fiddle. Iíll play a few jigs and hornpipes myself and I sing a few Irish songs. I just mix them in with the Scots songs now, as I am back in Scotland a good few years. But when you leave a country, and you go away to another country, you seem to forget about your Scots music. You lost it some, some songs now I sing Scotch bothy ballads like The Muckiní oí Geordieís Byre and all this. Well, Iíve lost some of the words of that now - being in Ireland so long, getting on to the Irish ones, you see. And I used to do very well at singiní The Buchan Bobby, The Moss oí Burreldale, but Iíve lost it altogether. Unless I hear somebody sing it, then itíll come back to my head again.

The settled traditional singers have an easier time. Walter Pardon could tell you which relative his clocks, furniture and songs came from, and the Coppers can trace individual songs back through generations. The "ganginí aboot folk" have of necessity to travel light and even for those who make their living through their music, it means that they sometimes have to leave their songs and music behind and take up new ones. Davie had a fairly large repertoire and he would adapt what he performed to what he felt his listeners would want or what the situation demanded. In the TMSA festival concerts, he would generally stick to a few of his big songs such as The Dowie Dens oí Yarrow, Bogieís Bonnie Belle and MacPhersonís Rant, and cleverly intersperse them with his comic pieces such as The Daft Piper and a few tunes on melodeon or whistle. If you caught him in a festival pub session, then he would produce something to reflect the mood of the session, including some rare ballads. The only Irish songs that, offhand, I can remember him still singing by the late 1960ís were The Galway Shawl and Boolavogue - to the same tune. By those years, he didnít seem to be singing that much of the standard bothy ballad repertoire that characterised the repertoires of many of old singers that the TMSA brought to the likes of Blairgowrie and Kinross. Yet the present recordings from 1957 have a high proportion of bothy songs and must have been close to the years when he was singing to the audience he loved best:

Davie Stewart: Well now, I often go away. But when Iím at home for a Saturday nightís playing, I usually go away on the Friday evening, maybe say, up to Aberdeen. Play, catch the football match there and get a few shillings - and then ahíd go around the town playing the picture hall queues, go to public houses entertaining people. The best of the lot is along with the farm servants. I always like to be in the bothy amongst the farm servant ploughmen because, eh, I do a lot of Scotch bothy ballads to them. And old songs, they like to hear me goiní to fairs singing. Iíve often had big crowds around me at night telliní me to "Go on, sing on another song".

So what about these songs? I can honestly say that I have never listened to an album that has given me more pleasure than this one, either just letting the sounds drift over me or trying to analyse carefully, it is amazingly rewarding listening.

Letís take Mormond Braes, for example. You wouldnít hear it sung these days. Many singers know it, but they would probably feel that it was too hackneyed to bring out.  Here it is an absolute delight. Davie starts off with a long A note and then touches that chord, before immediately starting off to play the tune in the key of E major. Perhaps he was "casting around for the key and tune" as Ewan McVicar suggests in his notes. Certainly it is characteristic of Davie to start playing notes from a different key from the one he settles to, but I think we need to be careful in ascribing this as a haphazard start for what sounds to me to be a deliberate technique. What instrument is he playing by the way? Certainly not the D/G melodeon that I photographed him with in 1970 (see right). Was it the button accordion that is pictured with on the Topic/Greentrax album? It may be that but Iíve also seen pictures of him with a battered old piano accordion and thatís what I think heís playing here. He plays the tune with some Scotch snap in the melody but fairly straight and slowish tempo, notably slower than the tempo he will be singing at by verse 3. He is just touching chords to give the melody a bit of rhythmic encouragement and most of them seem to be A chords. Now, conventional musical harmony rules would say that the tune would need mainly E chords with touches of A and perhaps a bit of B or B7. Donít tell me that Davie is wrong! I wonít have it. It immediately sounds weird, wonderful and interesting and right for what he is doing and thatís what matters. He sings the first verse at this tempo with the bass chords dropping out and the volume of the melody on the box held back. What of his voice? Clearly it has been honed by decades of street performance and projection is his number one aim above all, not shoutingly loud necessarily, but using vowel sounds that carry even if the diction has to suffer a bit. Generally, he keeps to the rhythm, but when he finds a sound that he likes he sustains it just a touch so we get in verse 1:

Here it is an absolute delight. Davie starts off with a long A note and then touches that chord, before immediately starting off to play the tune in the key of E major. Perhaps he was "casting around for the key and tune" as Ewan McVicar suggests in his notes. Certainly it is characteristic of Davie to start playing notes from a different key from the one he settles to, but I think we need to be careful in ascribing this as a haphazard start for what sounds to me to be a deliberate technique. What instrument is he playing by the way? Certainly not the D/G melodeon that I photographed him with in 1970 (see right). Was it the button accordion that is pictured with on the Topic/Greentrax album? It may be that but Iíve also seen pictures of him with a battered old piano accordion and thatís what I think heís playing here. He plays the tune with some Scotch snap in the melody but fairly straight and slowish tempo, notably slower than the tempo he will be singing at by verse 3. He is just touching chords to give the melody a bit of rhythmic encouragement and most of them seem to be A chords. Now, conventional musical harmony rules would say that the tune would need mainly E chords with touches of A and perhaps a bit of B or B7. Donít tell me that Davie is wrong! I wonít have it. It immediately sounds weird, wonderful and interesting and right for what he is doing and thatís what matters. He sings the first verse at this tempo with the bass chords dropping out and the volume of the melody on the box held back. What of his voice? Clearly it has been honed by decades of street performance and projection is his number one aim above all, not shoutingly loud necessarily, but using vowel sounds that carry even if the diction has to suffer a bit. Generally, he keeps to the rhythm, but when he finds a sound that he likes he sustains it just a touch so we get in verse 1:

His trueÖ love neíer returÖning

The chords return for the first line of the chorus and there is a very slight speeding of the tempo and Mormond gets a fair rolling of the 'r's. The link phrase between the first and second verse is pretty conventional except for his unique chords, the last melody line of the chorus is repeated, just a slight quickening of the tempo and then a longer held last note to enable him to come in at his original tempo on verse 2. Throughout this verse there is the characteristic feeling of Davie tugging the words against the rhythm; one of his most distinctive and delightful techniques. Then the chorus again; this time he employs a short break in the middle of the third line:

Mormond Hills farÖ.. (this note clipped - short break) heather grows.

It is very effective. The next link phase is the whole tune. The tempo is speeded considerably for this and strong emphasis is given to certain notes giving a strong lift. Again the last note is held and allowed to sustain itself through the first line of verse 3. It has died away by the end of that line and picks up again with the start of the second line - lovely! His singing is in full cry now and we are getting some wonderful full vowel sounds and he allows the tempo to build again slightly, No chorus this time, straight into verse 4 and the tempo continues to build slightly during the first two lines and than it slows down for the last two words ... gey sairly. Then much slower and with each word given great emphasis.

Many a deem has lost her lad

And gotten another richt early

Back to a slightly faster tempo to start another chorus, though in fact Davie allows the tempo to drop slightly as this chorus proceeds. Certain notes are really being punched hard now on both the accordion and the voice. The last line is played as a link phrase at the tempo he has been singing at then he steps up the tempo again to play the melody again, but differently this time. The chords are all held slightly longer without the punched effect and there are three places where there are suggestions of triplets, though in fact all the notes are allowed to run into one another at this playing. Loud chord at the end and then a slowing of the tempo for what is conventionally the last verse. Thereís as good fish ... and we are expecting the final chorus to follow, but whatís this? A bit slower:

But ahíll gang back tae Streechan toon,

An toss ma heid fu rarely

Then he will look at me

And then he will winner gey sairly

But ahíll mairry a lad frae Hatton Toon

His name is Willie Logie

Ahíll tak a place near Peterheid

A place they call Ciarranbrogie.

Where did that lot come from? Ewan McVicar notes "The last two verses do not appear in other versions - creations of Davieís own, or migrants from another song?" Hmm, the former, probably. Davie was always adding bits on at the ends of songs and if you listen to different recordings he never allows words or rhythms to settle down. His performances have a constant striving about them. Here we go now with the final chorus. The volume of the accordion is now raised again to the same volume as if it was being played in the link phrases. The last note of the second line is held and swelled and each word of the last two lines is delivered in a full a purposeful way with a wide range of vowel sound.

OK so Iím an anorak, donít worry it could have been worse. I even considered giving metronome markings for all the changes of tempo but I decided against it. The point that I am trying to make is this. I chose Mormond Braes because it was one of the shortest and simplest to analyse of the performances here, but in 3 Ĺ minutes there is so much going on. The breadth of his approaches to one song is stunning. And none of the above attempts to even mention the gut-wrenching emotional intensity of his singing. Davie may have had some musical training as a piper when he was in the army, but most of his musical strategies he must have worked out for himself and the fact is that in the main they defy musical convention. How are we to regard him then? Is he the musical equivalent of the naïve painter? Ewan McVicar again - "In his sketchy fill-ins, the final chord and bass notes vary and clash as though his mind was elsewhere." I canít agree. Certainly Davie and musical convention are miles apart, but this does not mean that he is in any way slapdash and disorganised. We need to listen to him with fresh open ears and allow him to break rules; true originals always did.

Generally, it is his bothy ballads that have the biggest impact here for these are the previously unreleased material.  None on his previous album - recordings from 1954-1962 - there are four here. Auld Jock Bruce oí The Fornet is by his standards, quite an understated performance. The tune is the the well-known Johnnie Cope, his text is garbled, his accent is at its thickest but it is still a very coherent, satisfying performance and the introduction he plays can only add to the sketchy vs. studied debate (sound clip). The opening track is another that makes a mighty impact soaring over his accordion and his free interpretation of a song that is normally sung in strict rhythm is most effective. Davie also recorded The Tarves Rant, singing unaccompanied, for Bill Leader and it appears on the 1968 Topic album, The Back oí Benachie. Like every other example that I can think of, his version on this album is superior; Lomax captured him on spectacular form.

None on his previous album - recordings from 1954-1962 - there are four here. Auld Jock Bruce oí The Fornet is by his standards, quite an understated performance. The tune is the the well-known Johnnie Cope, his text is garbled, his accent is at its thickest but it is still a very coherent, satisfying performance and the introduction he plays can only add to the sketchy vs. studied debate (sound clip). The opening track is another that makes a mighty impact soaring over his accordion and his free interpretation of a song that is normally sung in strict rhythm is most effective. Davie also recorded The Tarves Rant, singing unaccompanied, for Bill Leader and it appears on the 1968 Topic album, The Back oí Benachie. Like every other example that I can think of, his version on this album is superior; Lomax captured him on spectacular form.

The pick of the previously unissued items must be the one with all the traveller cant, Last Night I was in the Granzie (sound clip). Davie is at his most inventive all the way through it, he invents verses, chuckles with enjoyment at the way it is going, inserts some wild, unrelated but effective notes on the accordion. The whole thing is completely riveting, even after many listenings. The versions of MacPherson's and Dowie Dens seem to be the ones that were used in the famed Topic/ Caedmon so they are likely to be known to the long-term enthusiasts for traditional song, but they are still totally absorbing.

The pick of the previously unissued items must be the one with all the traveller cant, Last Night I was in the Granzie (sound clip). Davie is at his most inventive all the way through it, he invents verses, chuckles with enjoyment at the way it is going, inserts some wild, unrelated but effective notes on the accordion. The whole thing is completely riveting, even after many listenings. The versions of MacPherson's and Dowie Dens seem to be the ones that were used in the famed Topic/ Caedmon so they are likely to be known to the long-term enthusiasts for traditional song, but they are still totally absorbing.

As elsewhere in this series, there seems to be a lack of attention to detail in the documentation. This time itís the tray text numbering of the tracks which are numbered 1-10 and then 16-24, a bit irritating when you want to select an individual track. The main body of the notes is the essay on Davie by Hamish Henderson. This does a fine job of describing the man, but as it was also used, word for word, as the insert in the Topic album. It means that some us will now have the essay in our house four times as it appeared first in the magazine Tocher in 1974 and itís also reprinted in the collection of Hendersonís writing Alias MacAlias. The transcription of the words, song notes and an introduction are by Ewan MacVicar. I disgree with him in places, but it would be churlish not to note the overall excellent job that he has done, a considerable improvement on, for example, the transcriptions and background notes on earlier releases in this series.

We could have been offered some instrumental playing on pipes, whistle or accordion, but what has been included could scarcely be bettered.

Vic Smith - 27.2.02

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 27.2.02

The biography was assembled from the small number of articles and interviews with Davie that I was able to access plus some stories I had heard Davie himself tell; mostly these were written/conducted by Hamish Henderson. The information led me to state that 'Davie Stewart was born in 1901, the son and grandson of two Robert Stewarts, both travelling tinsmiths and hawkers, in the Buchan area, nobody seems to be exactly sure where'. Well, I did not have access to these Alan Lomax interviews when I wrote that. Here Davie dispels any romantic mystery surrounding his birth:

The biography was assembled from the small number of articles and interviews with Davie that I was able to access plus some stories I had heard Davie himself tell; mostly these were written/conducted by Hamish Henderson. The information led me to state that 'Davie Stewart was born in 1901, the son and grandson of two Robert Stewarts, both travelling tinsmiths and hawkers, in the Buchan area, nobody seems to be exactly sure where'. Well, I did not have access to these Alan Lomax interviews when I wrote that. Here Davie dispels any romantic mystery surrounding his birth:

Here it is an absolute delight. Davie starts off with a long A note and then touches that chord, before immediately starting off to play the tune in the key of E major. Perhaps he was "casting around for the key and tune" as Ewan McVicar suggests in his notes. Certainly it is characteristic of Davie to start playing notes from a different key from the one he settles to, but I think we need to be careful in ascribing this as a haphazard start for what sounds to me to be a deliberate technique. What instrument is he playing by the way? Certainly not the D/G melodeon that I photographed him with in 1970 (see right). Was it the button accordion that is pictured with on the Topic/Greentrax album? It may be that but Iíve also seen pictures of him with a battered old piano accordion and thatís what I think heís playing here. He plays the tune with some Scotch snap in the melody but fairly straight and slowish tempo, notably slower than the tempo he will be singing at by verse 3. He is just touching chords to give the melody a bit of rhythmic encouragement and most of them seem to be A chords. Now, conventional musical harmony rules would say that the tune would need mainly E chords with touches of A and perhaps a bit of B or B7. Donít tell me that Davie is wrong! I wonít have it. It immediately sounds weird, wonderful and interesting and right for what he is doing and thatís what matters. He sings the first verse at this tempo with the bass chords dropping out and the volume of the melody on the box held back. What of his voice? Clearly it has been honed by decades of street performance and projection is his number one aim above all, not shoutingly loud necessarily, but using vowel sounds that carry even if the diction has to suffer a bit. Generally, he keeps to the rhythm, but when he finds a sound that he likes he sustains it just a touch so we get in verse 1:

Here it is an absolute delight. Davie starts off with a long A note and then touches that chord, before immediately starting off to play the tune in the key of E major. Perhaps he was "casting around for the key and tune" as Ewan McVicar suggests in his notes. Certainly it is characteristic of Davie to start playing notes from a different key from the one he settles to, but I think we need to be careful in ascribing this as a haphazard start for what sounds to me to be a deliberate technique. What instrument is he playing by the way? Certainly not the D/G melodeon that I photographed him with in 1970 (see right). Was it the button accordion that is pictured with on the Topic/Greentrax album? It may be that but Iíve also seen pictures of him with a battered old piano accordion and thatís what I think heís playing here. He plays the tune with some Scotch snap in the melody but fairly straight and slowish tempo, notably slower than the tempo he will be singing at by verse 3. He is just touching chords to give the melody a bit of rhythmic encouragement and most of them seem to be A chords. Now, conventional musical harmony rules would say that the tune would need mainly E chords with touches of A and perhaps a bit of B or B7. Donít tell me that Davie is wrong! I wonít have it. It immediately sounds weird, wonderful and interesting and right for what he is doing and thatís what matters. He sings the first verse at this tempo with the bass chords dropping out and the volume of the melody on the box held back. What of his voice? Clearly it has been honed by decades of street performance and projection is his number one aim above all, not shoutingly loud necessarily, but using vowel sounds that carry even if the diction has to suffer a bit. Generally, he keeps to the rhythm, but when he finds a sound that he likes he sustains it just a touch so we get in verse 1: