The Flanagan Brothers

The Tunes we Like to Play on Paddy's Day

Viva Voce 007

Here is yet another delightful release from the label that is doing more for vintage Irish reissues than any other three companies combined. Not merely content to reissue indiscriminately, they make a real effort to programme items which have never appeared in print since the demise of the 78 r.p.m. format.

From the very first bar of The Cavan Reel the familiar combination of Joe's melodeon and Mike's tenor banjo lash out with fury, setting the standard for the majority of instrumental selections which follow. These are many and varied, with the usual reels and jigs well balanced by a fine array of flings, barndances, hornpipes, and even two-steps. The melodeon/banjo combination is the norm, but other instrumental juxtapositions are heard here also, including twin banjos (by Mike and another brother, Louis), and harmonica and jew's harp. The brothers' vibrant, joyous style propels the rhythmic pulse along at a great rate, while still maintaining a steady tempo. Only in the banjo duet does the rhythm falter to any appreciable extent. The inclusion of plenty of songs and a couple of sketches with incidental music all contribute to a release of great variety.

From the very first bar of The Cavan Reel the familiar combination of Joe's melodeon and Mike's tenor banjo lash out with fury, setting the standard for the majority of instrumental selections which follow. These are many and varied, with the usual reels and jigs well balanced by a fine array of flings, barndances, hornpipes, and even two-steps. The melodeon/banjo combination is the norm, but other instrumental juxtapositions are heard here also, including twin banjos (by Mike and another brother, Louis), and harmonica and jew's harp. The brothers' vibrant, joyous style propels the rhythmic pulse along at a great rate, while still maintaining a steady tempo. Only in the banjo duet does the rhythm falter to any appreciable extent. The inclusion of plenty of songs and a couple of sketches with incidental music all contribute to a release of great variety.

True to their historical period, several of their items contain racist and political overtones. In the comic skit Fun at Hogan's the stereotypical Italian tenor is silenced with "this is no spaghetti place... Goodbye and good luck to ye. If ye lever come back 'twill be time enough." And in Flanagans at St Patrick's Day Parade they comment of Father Duffy and His Fighting 69th Regiment, "T'would be lovely if they could all get together and win freedom for poor auld Ireland." Of course, their recording of The IRA Song was more overt, but the compilers have, perhaps wisely, omitted that one.

In the comic sketches some of the attempts at humour are a bit off the mark, but there are some fine moments, and it's all carried along with great verve and enthusiasm. In Fun at Hogan's we hear, "Say Hogan, what have you got in your hip pocket?" "Oh, that's laudanum." "What in the blazes is laudanum?" at which point they launch into what must rank as the most bizarre Irish diddling on record, in two-part baritone and falsetto harmony with guitar backing.

In general the transfers are just fine, let down only by two early acoustic tracks, and, rather surprisingly, the common Fun at Hogan's - the surface of which sounds worse than my 78 r.p.m. copy.

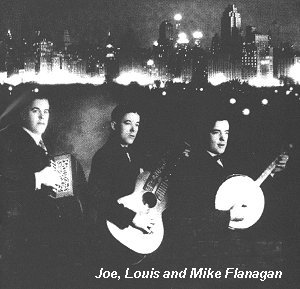

The booklet contains a wealth of useful information, several newspaper advertisements, and a little known photograph of the three brothers. In the area of biographical facts I have no quibble. Of the more abstract notions of perceived historical trends and influences, however, I have severe reservations. Harry Bradshaw is a knowledgeable researcher and it's not often that I disagree with what he has to say. His notes here, though, contain some worrying statements which are distinctly misleading.

I disagree entirely that Joe Flanagan helped to "create" that distinctive U.S. style of fast, staccato melodeon playing, full of cascading triplets, to which he aspired (page 7 of the insert booklet). On the evidence of the recorded output alone, John J. Kimmel had achieved that single-handedly some years before Joe even entered his teens. What influences crystallised to create a style apparently so outside of the mainstream Irish tradition we will never know. Kimmel, of course, was of Dutch descent, so may have been utilising techniques known elsewhere in Europe (though, if so, they were never otherwise recorded). But I'm certain that the father of the Flanagan boys didn't play his "single row accordion or melodeon" (page 2) in such a manner. Neither did Scottish players such as Peter and Daniel Wyper, James Brown, or 'Pamby' Dick, who recorded contemporaneously with Kimmel during the first decade of the century. Much more likely is that Kimmel was a manually-dexterous and mentally devious musical prodigy. The outputs of both Sligo fiddle player Michael Coleman, and the tinker Uilleann piper Johnny Doran exhibit similar attributes.

Kimmel's influence was almost completely pervasive, with practically every recorded Irish emigrant melodeon player who came after, whether first or second generation, consciously (I believe) striving to emulate his technique. Examples range from the anonymous player on one of vaudevillean Steve Porter's 1908 versions of Thim Were the Happy Days (aurally, it must be Kimmel himself on the other version), to Bostonian Joe Derrane, who even today can mimic the Kimmel style to perfection. But as good a melodeon player as Joe Flanagan was, and he was seldom short of excellent, his 1929 electrical remake of Kimmel's acoustic International Echoes of 1918, reveals that his technique falls quite a bit short of that heard on the original. Whereas Kimmel's triplets flow almost effortlessly from his instrument, seemingly without end, it is left to the banjo to provide that effect here. Listen to Joe trying to generate that style in The Miller of Drone and failing as often as not. All that said, where triplets occur on adjascent, as opposed to single, buttons he is just fine, as in The Rights of Man.

One man who stood more or less outside of that influence (although even he succumbed just a little at times) was Frank Quinn, originally from Co. Longford. Yet Harry Bradshaw lumps him together with Kimmel and his acolytes (page 7), thereby doing Quinn something of an injustice. It seems more likely that Quinn's melodeon style was closer to the style heard at home, perhaps even having a closer affinity with Flanagan père. If Joe Flanagan plays at all like his father it must surely come closest on the run through of The Teetotaller which precedes The Half Crown Song. It's about the only time, too, that the Scotch snap technique is in evidence.

Delving further into the notes, I hear nothing remotely resembling Jewish klezmer music in the three tracks singled out on page 8. The addition of a clarinet does not a disparate genre suggest. In fact, the Clarinet does little except pretend to be a trombone. The notes continue:

...The Columbia bosses were not unaware of this similarity for in 1927 the group recorded for the Polish market using the names 'Wesola Dwojka' (The Merry Duo) and ' Liaudies Orkestra'...

This is perhaps the most misleading statement of all. One track only - On the Road to the Fair - appeared in Columbia's various foreign series (including the Italian), and this was a rather musically (and therefore culturally) ill-defined polka played on jew's harp with guitar accompaniment. Both dance form and instruments are completely alien to the klezmer tradition, and it's about as far from that genre as one could get. All manner of non-Irish tunes and styles are grist to the Flanagans' mill, from Turkey in the Straw to Casey Jones (heard in the medley By Heck), but klezmer isn't one of them. Stylistically, in the former medley Joe is playing a Lot like a piano accordionist, replete with slushy phrases; while the melodeon used on track 18 seems to have some sort of vibrato attachment.

My final disagreement is in the claim for innovation by 'using a brass and woodwind ensemble on their recording of My Irish Molly O' (page 8). Rather the reverse I suspect. Both that track and many others in their recorded output, including The Grand Hotel in Castlebar, heard here, sounds like Frank Crummit with an Irish accent. That form of 'pit orchestra' backing, generally led by a 'straight' violin, has recorded antecedents dating almost to at least the turn of the century, as epitomised by such 'ethnic' vaudeville performers as Edward M. Favor and the aforementioned Steve Porter. Just as Crummit made several attempts at mock-Irishness, all of which were rejected by the recording company, the Flanagans' repertory contains several more overtly direct Crummit adaptations, though none are featured here.

Returning to the actual music, on the historical front, guitarist 'Whitey' Andrews' stock jazz chords on an item from Joe Flanagan's final session, in 1933, firmly transports us into a different era. By the time the Great Depression eased just a little later the melodeon seemed outmoded, and gave way to the dominance of the fiddle, paralleling trends in Cajun country. But for more than a decade the Flanagan brothers gave of their best to the record buying public. And much of that output was readily available in the U.K. during the inter-war period, the Columbia recordings most often on Regal (latterly Regal-Zonophone), and the Victor items on H.M.V. Judging by the frequency with which some of these turn up in junk shops they must have sold extremely well. Much scarcer are the pseudonymous releases of some of their pre-electrical items for smaller companies such as Gennett and Vocalion, on early UK labels Beltona, Aco and Guardsman. That they were fully appreciated within their own lifetime, both at home and abroad, is gratifying. Their output stands now as a musical moment in time, but the fact is that much of it remains vibrant even today. Harry Bradshaw has made a significant contribution to Irish music by compiling this CD. Definitely an all round winner.

Keith Chandler - 16.3.97

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 5.11.02

From the very first bar of The Cavan Reel the familiar combination of Joe's melodeon and Mike's tenor banjo lash out with fury, setting the standard for the majority of instrumental selections which follow. These are many and varied, with the usual reels and jigs well balanced by a fine array of flings, barndances, hornpipes, and even two-steps. The melodeon/banjo combination is the norm, but other instrumental juxtapositions are heard here also, including twin banjos (by Mike and another brother, Louis), and harmonica and jew's harp. The brothers' vibrant, joyous style propels the rhythmic pulse along at a great rate, while still maintaining a steady tempo. Only in the banjo duet does the rhythm falter to any appreciable extent. The inclusion of plenty of songs and a couple of sketches with incidental music all contribute to a release of great variety.

From the very first bar of The Cavan Reel the familiar combination of Joe's melodeon and Mike's tenor banjo lash out with fury, setting the standard for the majority of instrumental selections which follow. These are many and varied, with the usual reels and jigs well balanced by a fine array of flings, barndances, hornpipes, and even two-steps. The melodeon/banjo combination is the norm, but other instrumental juxtapositions are heard here also, including twin banjos (by Mike and another brother, Louis), and harmonica and jew's harp. The brothers' vibrant, joyous style propels the rhythmic pulse along at a great rate, while still maintaining a steady tempo. Only in the banjo duet does the rhythm falter to any appreciable extent. The inclusion of plenty of songs and a couple of sketches with incidental music all contribute to a release of great variety.