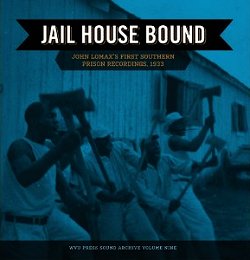

John Lomax's first Southern prison recordinggs, 1933

WVU Press Sound Archive WVU 9

1 - Rattler by Mose “Clear Rock” Platt; 2 - That’s Alright, Honey by Mose “Clear Rock” Platt; 3 - The Midnight Special by Ernest “Mexico” Williams; 4 - Ain’t No More Cane on the Brazos by Ernest “Mexico” Williams 1933; 5 - Ain’t No More Cane on the Brazos by Ernest “Mexico” Williams with James “Iron Head” Baker; 6 - My Yellow Gal by James “Iron Head” Baker with R D Allen and Will Crosby; 7 - Black Betty by James “Iron Head” Baker with R D Allen and Will Crosby; 8 - The Grey Goose by James “Iron Head” Baker with R D Allen and Will Crosby; 9 - Long Gone by “Lightening” Washington; 10 - Long John by “Lightening” Washington; 11 - Good God Almighty by “Lightening” Washington; 12 - Stewball; 13 - John Henry; 14 - He Never Said a Mumbling Word; 15 - Rosie; 16 - Alabama Bound by “Bowlegs”; 17 - Jumpin Judy; 18 - John Henry; 19 - Jumpin Judy by Allen Prothero; 20 - Sit Down, Servant by Adie Corbin and Ed Frierson; 21 - Levee Camp Holler by John “Black Sampson” Gibson; 22 - Track Lining Song by John “Black Sampson” Gibson; 23 - Steel Laying Holler by Rochelle Harris; 24 - Interview with John Lomax, 1933.

The work of Lomax the father gets rather less attention nowadays than that of Lomax the son, yet arguably John was the greater innovator than Alan, who largely followed in his father's footsteps (including, it has to be said, with regard to some rather dubious perspectives on authorship and copyright). I think posterity often tends to think of John Lomax as an old-school Southern white man who viewed the subjects of his research as ethnomusicological specimens, very much a product of his background and his environment. The photograph of him on the inside of this package, hat on head, cigar in hand, looking almost disdainfully into the camera, speaks to this image of the man, although maybe that's a reflection of our own contemporary prejudices as much as anything. By contrast, photographs of Alan frequently show him bearded, jovial, casually dressed and with guitar in hand.

The work of Lomax the father gets rather less attention nowadays than that of Lomax the son, yet arguably John was the greater innovator than Alan, who largely followed in his father's footsteps (including, it has to be said, with regard to some rather dubious perspectives on authorship and copyright). I think posterity often tends to think of John Lomax as an old-school Southern white man who viewed the subjects of his research as ethnomusicological specimens, very much a product of his background and his environment. The photograph of him on the inside of this package, hat on head, cigar in hand, looking almost disdainfully into the camera, speaks to this image of the man, although maybe that's a reflection of our own contemporary prejudices as much as anything. By contrast, photographs of Alan frequently show him bearded, jovial, casually dressed and with guitar in hand.

But without John there would have been no Alan, and I don't just mean that in the obvious sense. John's classic collection Cowboy Songs and other Frontier Ballads had been published in 1910, five years before Alan was born. Through that, and other work, he was an important pioneer both in the role of folksong collector, and in establishing folk songs and music as legitimate subjects for academic interest. It was John who established the key relationship with the Library of Congress, which would prove vital as a source of funding, equipment and - maybe just as importantly - of official status. That imprimatur was, no doubt, of vital importance in gaining access to the kinds of places where both Lomaxes collected some of their most valuable music. At this distance, perhaps we forget just how strange and bold it must have been to turn up at one of the notorious, brutal Southern prison farms and blithely ask the boss if you could record and photograph the inmates engaged in their hard labour.

It could be argued that by focusing on the men who recorded this music - I've devoted the first two paragraphs of this review to them - we do a disservice to the men who actually made the music, whose art this actually was. But while we know a great deal about the collectors, we know very little about the singers. Here, complete, is the account given in the booklet (which is well designed and contains useful historical background and song annotations) of the three singers the Lomaxes recorded at the Central Texas State Prison Farm, Sugar Land:

After Sugar Land, the Lomaxes moved on to Darrington State Prison Farm, where they recorded Lightnin' Washington. He sang Long Gone aka Long John (there are two versions here under these different titles); the booklet notes are a little ambiguous, seeming to suggest that this derives from W C Handy's Long John from Bowling Green, which Handy based on a traditional song. There's a connection, of course, but clearly it's that the song here derives from the same original source as Handy's. There's a strong Texas connection, in any case, and the electric blues I'm Long, Long Gone recorded by Texan Frankie Lee Sims in 1953 (Specialty 478) is essentially the same song, and definitely not via Handy. The second version here has a big-sounding group of accompanying voices, as well as axes whacking out the rhythm, as does the following Good God Almighty, with some of the chorus offering the occasional harmony, adding richness and strength to an already potent performance.

There are four songs from unidentified singers at Mississippi prisons, including a fine Stewball at Oakley, with group responses (Incidentally, the name derives from 'skewbald' a type of horse, rather than the name of a particular horse. Wikipedia: 'A skewbald horse has a coat made up of white patches on a non-black base coat, such as chestnut, bay, or any color besides black coat.'), and an equally fine John Henry. At Parchman, the group singing He Never Said A Mumbling Word is less like a work-song group than a gospel group, not formally arranged, probably, but influenced by ones that were, presumably in the outside world. Rosie, on the other hand, has that amazing and unique vocal sound that only ever emerged from a group of Southern prisoners singing at their work, the voices soaring, resonating, the harmonies wild and imprecise but enormously affecting.

Across the state border into Tennessee, the Lomaxes recorded more singers at the Shelby County Workhouse in Memphis. Jumpin' Judy again seems to me to have a little of the air of an arranged sound - some of these singers may well have sung quartet harmonies in the past - but the background thud of axes ensure that the listener is only too well aware that this is working singing. A similar group sings John Henry, and it's that interesting both they and the Oakley group insert lines not usually associated with that song, but with an old-world ballad: 'Who's gonna shoe your feet, who's going to glove your hand, who's going to kiss your rosy cheeks, who's going to be your man?' - well-travelled, well-used lyrics (from the Scottish original The Lass Of Roch Royal, Child 76) that somehow manage to fit neatly into the story of the steel-driving man.

At the Tennessee State Prison in Nashville, Adie Corbin and Ed Frierson sang Sit Down Servant in a carefully arranged and beautifully harmonised rendition that owes everything to the then-developing gospel quartet tradition we know from commercial recordings. In fact, this is the only performance here that shows any kind of explicit relationship with recorded styles, which isn't to say that a record was the direct influence (in fact, the notes say that it is 'distinct from other published and recorded versions available in the 1930s', although I'm not sure we could assert that with complete authority), so much as that, before they were incarcerated, these men were probably involved in a group (or in separate groups) of the same kind as made records. In any case, it is a delightful rendition, and quite unlike anything else on this disc. Also at Nashville, John 'Black Sampson' Gibson was persuaded (against his inclination, as he had 'taken up the sanctified life') to sing two solo songs - Levee Camp Holler and Track Lining Song. The solo context gives them a lonesome sound, and even a more primitive aspect, but in fact these would have been group songs, too, as would Rochelle Harris's Steel Laying Holler. There was a time when hollers of this kind were said to represent the origin of the blues, but such a simplistic view is pretty much discredited now.

The disc concludes with a short spoken explanation, by John Lomax in 1934, of why he recorded in prisons, which is to the effect that he reckoned that the most distinctively African-American sounds would be found in places where black people were most isolated from whites, and prisons were one such environment. Of course, Lomax does not use the term 'African-American', or even 'black', and the language he does use might be seen by some as reinforcing the image of his that I described at the start of this review. It's common to point out, in Lomax's defence, that he was a man of his time and place, and men of his time and place used language like that. This is, of course, true but we shouldn't let it obscure the fact that it was a time of harsh racism and white dominance, and a place - the Southern States - where those both of those were still exercised very strongly, and with great prejudice. Language always played a part in that. We have no way of knowing the truth of why all those men came to be incarcerated, or the facts about the terrible things that they may have done, or the extent to which their predicament was precipitated by the context of the deeply bigoted society in which they lived. But we can know of their ability to make great music, using only their voices (all of these recordings are unaccompanied by any musical instrument, apart from in some cases the percussion of their work-tools). For that we can be thankful to them. John Lomax respected his sources enough to believe quite genuinely that, as it says in the booklet, these songs represented 'a great, undocumented source of literature', and so he captured and preserved the sound of those voices. For that we can be thankful to him.

Ray Templeton - 9.5.12

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |