As an interpreter of traditional songs and ballads, the power, passion, intensity and beauty of her singing has never been bettered in my opinion and there is much here to soothe and delight the ear.

As an interpreter of traditional songs and ballads, the power, passion, intensity and beauty of her singing has never been bettered in my opinion and there is much here to soothe and delight the ear.

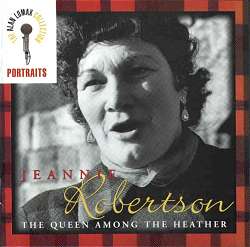

The Queen Among the Heather (Alan Lomax Collection: Portraits)

Rounder 1720

In the autumn of 1950, Alan Lomax first came to Scotland to record material for the Columbia Records for their World Library of Folk and Primitive Music series. He had already established that introductions to the singers would be set up by his established contacts; Hamish Henderson, Calum I MacLean and Sorley MacLean. In a 1985 edition of 'Tocher', Hamish explained the programme. "I agreed to assist him in the North-East and asked Sorley and Calum to do likewise in the Gaelic-speaking West, pointing out that the tape-recorder he had brought with him was streets ahead of any other portable recording machine I had so far encountered, and that this seemed a golden opportunity to put on record a good number of the virtuoso tradition-bearers known to them. Both readily and generously agreed to help him, and the result was the first twenty-five copy-tapes in our sound archive."

"Our sound archive?" Well, yes, these were the first tapes to find their way into that vast collection of sound recordings that exists in the School of Scottish Studies of Edinburgh University, probably the finest, most comprehensive - if not the most accessible - national archive of traditional song, music, stories and lore in the world.

The quotation gives some insight into the mind-set that existed at the time. In ragged-arsed, rationed-booked, post-war Britain, there were people who thought that traditional culture was important enough to be worth preserving; but where would this fit into the overall economic rebuilding scheme of things? Suddenly, there arrived of the scene, this relatively rich, confident, technically competent, can-do, go-getter Yank who pointed the way. It's no wonder that Hamish, Ewan MacColl et al thought that the sun shone out a certain part of the Lomax anatomy. No wonder, either, that a younger generation of enthusiasts has reacted against the near-deity status that was accorded to Lomax.

One more contextualising quotation from Hamish before we proceed to the album itself, this time from a 1977 'Tocher'. Hamish is surveying commercially available recordings of traditional Scots song - "First in the field by a long chalk was Columbia, which in 1950 commissioned Alan Lomax ... to compile and edit and series of LPs ... and liaise with the various folklore institutes that were willing to co-operate. In Scotland, there being as yet no School of Scottish Studies, he found himself obliged to operate through individual collectors."

Here I must ask you to read my comments alongside Danny Stradling's review of Margaret Barry's album in this series. My reservations and conclusions on this album are remarkably similar to hers on Margaret's, though I will try to avoid being repetitious.

It was three years after Alan's first visit to Scotland, that Hamish first encountered Jeannie in Aberdeen, following up a lead from another traveller. It's been suggested to me on more than occasion that Hamish took some time to realise the importance of the majestic singer that he had encountered. Whatever the truth of the matter, here was someone very special indeed. Soon, the academics and critics associated with balladry, folk song and lore would be queuing up to heap praise on this Aberdeenshire traveller. Listening to these recordings, it is very difficult not to go along with every effusive word.  As an interpreter of traditional songs and ballads, the power, passion, intensity and beauty of her singing has never been bettered in my opinion and there is much here to soothe and delight the ear.

As an interpreter of traditional songs and ballads, the power, passion, intensity and beauty of her singing has never been bettered in my opinion and there is much here to soothe and delight the ear.

These are amongst the earliest recordings of Jeannie's and she is in great form throughout. The power and purity of her singing here is unmatched in her later recordings. The pace? Well, that has been a problem with Jeannie's singing for some people. It is the only criticism of Jeannie's singing that I am prepared to allow. Sometimes she is simply demonstrating the sheer beauty of that wonderful instrument that is her voice and the story of the song gets neglected. I've been doing a lot of timing of tracks here and comparing them with her later, commercially available recordings. In every case where it is possible to make a direct comparison, the later recordings are longer, obviously indicating a slower pace. Even so, there are items here when she is in no rush! In the song that is normally called What A Voice and here called When My Apron Hung Low, she takes nearly six and a half minutes to deliver the song's 23 lines, and 22 seconds to deliver the words "And he tells ... her a tale ... that he once told me." ![]() The swells and pauses in the middle of a line are magnificent, but they do interfere with the flow of the meaning of the words. On the other hand, by her own standards she is positively rushing one of her best known ballads, My Son David (sound clip), but I feel that the performance of this song, always very moving, is enhanced at this pace.

The swells and pauses in the middle of a line are magnificent, but they do interfere with the flow of the meaning of the words. On the other hand, by her own standards she is positively rushing one of her best known ballads, My Son David (sound clip), but I feel that the performance of this song, always very moving, is enhanced at this pace.

Just why did she slow down her singing, the more she sang in public? That is the interesting question. I was taken to task earlier this year in the letter pages of fRoots magazine for suggesting that "There is no doubt that in later years, Jeannie's head was turned by the vast number of compliments that came her way from the academic community." In many ways, Jeannie was "the modest lady living a modest life" that my critic suggested, but I stand by my comments and would go further to suggest that the mountains of praise were the direct reasons for her changing and slowing her singing style. I find much to dislike in Matthew Barton's booklet notes, but I must concur when he states that "... her singing in later years became more dramatic, even operatic in scale and pathos, as she sang for a more urban, non-traveler [sic] audience. The early recordings ... heard here preserve a less assimilated but more precise and powerful style."

Jeannie's repertoire of songs was huge and wide. The wonder was that there were so many great versions of the old ballads amongst them and a number are here including Son David, Lord Lovatt, thirteen and a half minutes of The Mill O' Tifty's Annie, (here called Bonnie Annie and Andrew Lammie) and the title track. These were the songs that attracted all the folklorists, but Jeannie loved all her songs, and away from the concert/festival stage she would often choose to sing her more bawdy sexual encounter songs. Strangely enough, it's not the big ballads that make the mightiest impact here. ![]() She often tackles songs that are a lot stronger than Wi' My Roving Eye (The Overgate), She Was A Rum One and Never Wed An Old Man (sound clip), but her interpretative talent transforms even these slighter pieces into compulsive listening. Rabelais himself would surely have delighted in the last named.

She often tackles songs that are a lot stronger than Wi' My Roving Eye (The Overgate), She Was A Rum One and Never Wed An Old Man (sound clip), but her interpretative talent transforms even these slighter pieces into compulsive listening. Rabelais himself would surely have delighted in the last named. ![]() If I were asked to name a favourite, it would have to be the one song of Jeannie's that I was unfamiliar with - the way she tells the story of The Handsome Cabin Boy (sound clip) is a tour de force.

If I were asked to name a favourite, it would have to be the one song of Jeannie's that I was unfamiliar with - the way she tells the story of The Handsome Cabin Boy (sound clip) is a tour de force.

There are five sections of interview between Lomax and Jeannie to go with the thirteen songs. My opinion on these has slowly changed with much repeated listening. Initially I cringed at how stilted Jeannie sounded - ill at ease, trying to sort out what this man was after, not at all the relaxed, jokey, cheery person that I remember talking to. And surely he is asking all the wrong questions? Gradually, I came to realise the reasons why. These conversations were recorded on a rare visit to London, whereas almost every time I talked to Jeannie it was on her own ground, at her home in Aberdeen. By then she was used to and confident with the folk scene's pilgrims. Lomax was thousands of miles culturally and economically as well as geographically away from an Aberdeenshire traveller. How could he have known what to ask? He concentrates on the content of the songs and where they were learned from and where they would be sung. These are important questions. They may not have troubled Sharp, Vaughan Williams etc. 50 years earlier. A further 45 years and it is difficult to remember that Lomax was pioneering the process of trying to contextualise the material he was recording.

I don't propose to spend long on discussing the booklet beyond expressing disappointment and wondering, with Danny Stradling in the Margaret Barry review, why on earth the job was given to Matthew Barton. He starts off very unpromisingly by changing Ailie Munro's gender in the first paragraph and fails to improve. There are plenty of people still around who knew Jeannie well and could have written about the wonderful, enigmatic person that she was. The facts are fine, but what was surely needed was a warts'n'all portrait of her great charms and idiosyncracies. She had enough of both to fill several books. Why wasn't, let's say, Ray Fisher asked to contribute an essay? She has a fund of Jeannie stories as well as great love and admiration for the woman.

The notes reach their nadir when we come to the transcription of the words. I'll just mention a couple. In Wi' My Roving Eye the ploughboy is asked to "gae hame tae Auchterady" - whereas to be reunited with The Proclaimers and Jimmy Shand, he needed to return to Auchtermuchty. And then a really lovely one in The Battle o' Harlaw:

"It's did you come frae the hielands, man,Well, no, he didn't. The journey was from Skye to Aberdeenshire, so there seemed little point in making a diversion to Mid-Wales or Herefordshire just to cross a river.

And did you come o'er the Wye?"

However, in the end we need to put the booklet aside. The recordings are amongst the finest I've heard of the woman who is claimed by many to be Britain's foremost traditional singer and nine of the thirteen songs have never been available commercially before. This would seem to make the album indispensible.

I'll finish with a little story. Earlier this year, we had Sheila Stewart staying with us. She was telling us about the album that she had just recorded for release by Topic and she showed me the order of the track listing that had been settled on. In my turn, I showed her the CD re-release of her mother, Belle's album, Queen Among the Heather on the Greentrax label. (I was surprised to hear her say that she knew nothing of the arrangement for the Topic album to be licensed and re-released). I then showed her this album, The Queen Among the Heather, released around the same time and asked her to consider what two of Scotland's great traveller singers would have said if they had been alive when these albums had come out. This greatly amused Sheila as she laughingly speculated on the comments that might have been made on both sides. I then asked her what the title of her forthcoming album was to be and she told me that this was yet to be decided. I said that it was quite common to call the album by the opening track. She looked again at the track listing and saw that the first song was called ... Queen Among the Heather. She fixed me with a stare with her penetrating black eyes and called me something that I don't care to repeat here.

Vic Smith - 30.10.99

| Top of page | Home Page | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |