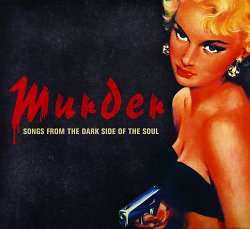

Songs from the Dark Side of the Soul

Various performers

Trikont 0399

Jimmie Rodgers: Gamblin' Bar Room Blues 2; Ethel Waters: Frankie and Johnny; Sonny Boy Williamson: Your Funeral My Trial [sic]; Lord Executor: Seven Skeletons Found in the Yard; Billy Boy Arnold: Prisoner's Plea; Wilmoth Houdini and His Humming Birds: Bandsman Shooting Case; Roosevelt Sykes 'The Honey Dripper': 44 Blues; Memphis Minnie: Biting Bug Blues; Bessie Smith & Her Blue Boys: Send Me to the 'lectric Chair; Wade Mainer - Zeke Morris: Down in the Willow; Blind Boy Fuller: Pistol Slapper Blues/; A'nt Idy Harper & the Coon Creek Girls: Poor Naomi Wise; Honeyboy: Bloodstains on the Wall; Little Walter and His Jukes: Boom Boom, Out Goes the Light; Louis Armstrong with Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five: You Rascal, You (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead); Champion Jack Dupree: I'm Going Down with You; The Stanley Brothers: Pretty Polly; Archibald: Stack-A-Lee Parts 1 & 2; Henry Thomas 'Ragtime Texas': Bob McKinney; G B Grayson - Henry Whitter: Rose Conley; Billie Holiday: Strange Fruit; Lonnie Johnson: Got the Blues for Murder Only; The Delmore Brothers: The Fugitive's Lament.

As Keith Chandler observes in his introductory essay, murder has been an abiding fascination 'since the days of Cain and Abel.' The philosophical, moral and existential implications of our capacity to take another's life (or indeed our own) obviously raise plenty of important and difficult questions, as does the issue of what retribution should be applied and by whom. It sometimes seems odd to me, avid reader of detective novels and thrillers though I am, that violent death at the hands of another is the mainspring of an escapist genre; but displacing the horrid realities into entertainment is one way to make the thought of them manageable, and until recently most whodunits carried an implicit or explicit moral message in their climactic unveiling of the villain, and his or her consignment to justice.

As Keith Chandler observes in his introductory essay, murder has been an abiding fascination 'since the days of Cain and Abel.' The philosophical, moral and existential implications of our capacity to take another's life (or indeed our own) obviously raise plenty of important and difficult questions, as does the issue of what retribution should be applied and by whom. It sometimes seems odd to me, avid reader of detective novels and thrillers though I am, that violent death at the hands of another is the mainspring of an escapist genre; but displacing the horrid realities into entertainment is one way to make the thought of them manageable, and until recently most whodunits carried an implicit or explicit moral message in their climactic unveiling of the villain, and his or her consignment to justice.

Similarly, it's no surprise that murder has been a prolific source of inspiration for folk and popular musicians worldwide. All but two of this disc's 23 tracks were recorded by American artists (and of the two calypsos, Houdini's was recorded in New York.) The Trinidadian numbers are typical calypsos, describing and commenting on topical events with an up-to-the-minute freshness which ensures that their subjects are entirely obscure to later listeners without research. It's regrettable, therefore, that there's no factual background supplied for either of these songs in the notes, nor for most of the (surprisingly few) others with a factual basis.

This may be as good a place as any to point out a couple of errors in the brief (often too brief) notes on each track: 'Elmar, Arkansas,' often given as Roosevelt Sykes' birthplace, doesn't exist; it's probably an ancient mishearing of Helena, Arkansas, reproduced by succeeding writers, this one included. The way that Sonny Boy Williamson's baby loves is a solid sender, not 'a solid sentiment,' and he didn't 'allegedly stab a man during a street fight, and abruptly return to the US' during the AFBF tour; he did pull a knife on Howlin' Wolf in a hotel, but he stayed on after the tour, and went home because of work permit problems, and a lawsuit he was pursuing in Arkansas. Not an error, but an omission: it's noted that Lonnie Johnson played fiddle and banjo as well as guitar, but he was also a pretty fair pianist.

What, anyway, of the musical and documentary merits of the tracks themselves? I may be wrong in detecting a wish to avoid the usual, and sometimes over-used selections found on compilations of this sort, which may account for the absence of the likes of Lead Belly, John Hurt (Frankie, Stack O'Lee Blues, Louis Collins) and Furry Lewis (Billy Lyons and Stack O'Lee). Europe's 50-year mechanical copyright limit is also taken advantage of, and enables the inclusion of a good many songs of comparatively recent vintage.

The disc kicks off very well, with an intriguing mix of styles and genres. Jimmie Rodgers draws on stereotypes of black violence as well as his close acquaintance with black music, but his world-weary display of early outlaw chic is compellingly disengaged from moral issues. Ethel Waters benefits from the most swinging band that ever backed her, and a rewrite of the familiar tale that encourages her to take rhythmic liberties. (It also explicitly sets the shooting in a brothel; unexpected on a record released in Bluebird's pop series.) Rice Miller threatens murder with outstanding rhythmic energy, abetted by the Chess house band at its best. Billy Boy Arnold's song is based on Southern worksong cadences, surprisingly for a 22-year old native of Chicago recording in 1957. The calypsos I've already discussed, but it's worth singling out the sour but lively saxes on Executor's track, and the flute's birdsong obbligatos on Houdini's. The Honey Dripper handles the polyrhythms of 44 Blues with aplomb, and furnishes the tune with a clever lyric.

At this point, unfortunately, some of the compiler's inspiration seems to desert him. Memphis Minnie's song is a musically routine effort, from a time when she was turning out records like Ford was turning out Model T's. Bessie Smith's recycling of 'Ju-udge, ju-udge,' on the same two notes and with identical inflection, renders Send Me To The 'lectric Chair dull, despite the presence of Joe Smith and Charlie Green on cornet and trombone. Down In The Willow is a cover of Rose Conley; both versions have considerable merit, but it seems lazy to include both, when there are so many other songs to select from. (Not to review the record one wishes one had been sent, but what about McKinley or another ballad of political assassination, or Pat Hare's chilling, accidentally prophetic I'm Gonna Murder My Baby?)

Pistol Slapper Blues is not one of Blind Boy Fuller's strongest compositions, and he soon resorts to stringing together random verses, which can be a successful compositional principle, but isn't here. Little Walter's track, on the other hand, is all too structured, one of those list songs that Willie Dixon could (and I sometimes think, did) write in his sleep. Still, there's more great playing from the Chess sessioneers and of course, Walter, as compensation. Bloodstains on the Wall by Honeyboy (real name Frank Patt) features urgent guitar from Joe Liggins, and a hook that is either bad writing, or a remarkable expression of panic and terror, whose hallucinatory atmosphere recalls Edgar Allen Poe:

Sheets and pillows torn to pieces, bloodstain all over the wall x2Either way, it's a lot better than A'nt Idy Harper's up-tempo trot through Poor Naomi Wise; as Keith Chandler observes, her delivery reflects her background as a rustic comedienne, but it's not to the song's advantage. She delivers it rather like a Southern, female George Formby (I'm leaning on a scaffold at the corner of the street…)

Well, I know I wasn't injured when I left this mornin', I didn't leave the phone out in the hall.

As I said to the editor when offered this CD, it's hard to imagine either of the Louises - Armstrong or Jordan - as exponents of the dark side of the soul, and their duet is nothing but fun, notwithstanding its subject; perhaps a musical equivalent of the displacement offered by whodunits? Nobody could slip in a reference to cunnilingus more gleefully than Satchmo does: You asked my wife for some cabbage, and you ate just like a savage. No such light-heartedness attends Billie Holiday's famous rendition of Herb Meeropol's Strange Fruit. I wished above for the inclusion of a song of political assassination, but of course this is such a one; lynching was part of the range of weapons used to intimidate black Southerners and exclude them from political processes and social advancement. The song is musically jarring in this context, and emotionally jarring in any context, as was rightly intended.

Of the other tracks, the Stanley Brothers Pretty Polly seems to be included to cover the bluegrass base; as with A'nt Idy Harper, but to a lesser degree, its fast tempo leaches some of the horror out of the song, which in versions by Dock Boggs and B F Shelton is one of the great musical manifestations of affectless psychopathy. Jack Dupree's song is uninteresting, particularly by contrast with his fellow New Orleanian Archibald's raw-boned, two-part Stack-A-Lee; probably an inspiration for Lloyd Price's hit version, but much less cosy. From there to Bob McKinney is an abrupt musical transition. The performance is a medley; after just over a minute Ragtime Texas abandons the badman in favour of Take Me Back and Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor before reverting to violence with Looking for the Bully of the Town. Henry Thomas's simple, chugging rhythms are a long way from Lonnie Johnson's gorgeous tones and fancy chords, which accompany a scurrilous enumeration of the alleged violent ways of Mexicans.

The final track stays out on the frontier - an imaginary one, constructed by Hollywood, the Sons of the Pioneers and other wanabee cowpokes:

I'm ridin' along out on the Lone Prairie, the Rangers are searching for me,It's perhaps unfair, but that won't stop me, to suggest that the Delmore Brothers' jog-along rhythms and high, close-harmony vocals are distantly reminiscent of Pinky and Perky. The Fugitive's Lament makes a weak closer to a collection that's a very mixed bag: there are some imaginative choices of material, but also too many tracks where the lyrics, the delivery or both don't do justice to the savage social, physical and psychological realities of the subject matter.

I'm riding away from my home in Texas, a fugitive ever to be.

Chris Smith - 5.1.10

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |