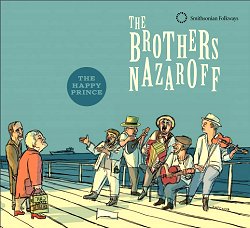

The Happy Prince

Smithsonian Folkways SFW-CD-40571

1. Vander Ich Mir Lustig (While I’m Happily Walking); 2. Tumbala Laika; 3. Ihr Fregt Mich Vos Ich Troier (You Ask Me Why I’m Mournful); 4. Arum Dem Feier (Around the Fire); 5. Freilachs (Medley of Freilachs); 6. Maidlach Vie Blumen (Girls Are Like Flowers); 7. Der Koptzen (The Poor Man; 8. Fishalach (Little Fish); 9. Ich A Mazeldicker Yid (Oh! Am I a “Mazeldicker” Jew!); 10. Maidlid (Maiden Song); 11. Ich Flee (I Fly); 12. Yiddel Mit Zein Fidel (Little Jew with His Fiddle); 13. Krasnoarmeyskaya Pesn’ (Red Army Song); 14. Now Sing Along With The “Prince” (Hava Nagila)

The last seventy-five years have not been good to Yiddish culture - all but wiped out in Eastern Europe, assimilated into near-obsolescence in America, and largely eclipsed by modern Hebrew in Israel. But it is far from dead. Gaining momentum alongside the klezmer revival of the past thirty years is a growing constituency of folk musicians and singers (both religious and secular) who are choosing Yiddish as one of the languages in which to write and perform their material. These artists also dedicate themselves to the rediscovery of unknown gems. This recording, by some of the very best, is a lively part of that process.

The last seventy-five years have not been good to Yiddish culture - all but wiped out in Eastern Europe, assimilated into near-obsolescence in America, and largely eclipsed by modern Hebrew in Israel. But it is far from dead. Gaining momentum alongside the klezmer revival of the past thirty years is a growing constituency of folk musicians and singers (both religious and secular) who are choosing Yiddish as one of the languages in which to write and perform their material. These artists also dedicate themselves to the rediscovery of unknown gems. This recording, by some of the very best, is a lively part of that process.

Today's mainstream Yiddish canon inevitably draws heavily on the rich traditional repertoire for which the genre is well-known. This frequently means navigating varying levels of kitsch: one can at times feel somewhat outnumbered by cabals of Yiddishe Mamas, surrounded on all sides by lost barefoot maidens, or thoroughly overwhelmed by happy dancing rabbis. This disc is not like that. It surely offers an engagement with Yiddish musical history, but of a refreshingly different kind, eschewing easy nostalgia in favour of a raw and infectious good-time spirit. It is an important contribution, but one which is unaffected, witty and deceptively simple. It is affirmative but not heavy-handed, funny but not glib.

Nathan "Prince" Nazaroff was a mysterious figure. It is likely that he was born in Russia in 1892 and came to America in 1914. His publicity material (possibly self-penned) dubs him, somewhat hopefully, a "big hit on Broadway", but very little is actually known about Nazaroff other than the handful of recordings he left behind - a few for for Columbia in the 1920s and twelve for Moses Asch's Folkways in 1954 (three more reels exist in the Folkways archives, as yet unreleased). He played the mandolin's lesser-known big cousin, the octophone. He re-wrote Yiddish classics like Tum Balalaika and borrowed melodies from Russian folk tunes like Din Din Din, endowing them with his particular brand of vodka-soaked Bacchanalia and contemporary social realism.

But whilst his own biography is murky and inconclusive, the Prince's spirit is alive and well, living simultaneously in Berlin, New York, Budapest, Moscow and Crail. Six of contemporary Jewish music's leading singers and musicians have taken it upon themselves to recreate Nazaroff's raucous blend of Yiddish and Russian party music, and this they do with joy, humour, and consummate musicianship. The geographies that these musicians cover is testament to the internationalism of today's Yiddish musical community - as a language no longer in possession of a definitive 'home', this is a culture which now exists most creatively across national borders rather than within them. And in truth, this is not so much a band as a bunch of like-minded friends who all met through other projects and have, by the looks of the recording data, grabbed the opportunities as, when and where they could to get together over a period of four years to record this album.

Singer and accordionist Daniel Kahn, Michigan-born but a Berliner for the past decade, is one of contemporary Yiddish music's busiest driving forces, both as a solo artist, collaborator and with his band The Painted Bird. Michael Alpert, originally from Los Angeles but these days resident in Fife, was a founder member of at least two seminal klezmer revival bands (Kapelye and Brave Old World) and is one of the finest living exponents of Yiddish song. New York fiddle-player Jake Shulman-Ment is widely acknowledged as amongst the best of today's crop of young klezmer musicians. Mandolinist Bob Cohen, an American Budapester, has been a central member of the Hungarian klezmer band Di Naye Kapelye for over twenty years. Muscovite and agent provocateur Psoy Korolenko is a singer, pianist and multi-lingual composer, recently involved in the "Yiddish Glory" project which brings to light recently discovered wartime Soviet Yiddish songs. And Malmö-born drummer Hampus Melin, also a long-time Berlin resident, is a rock-solid presence on Europe's klezmer scene in Berlin, Krakow, Vienna and beyond.

Prince Nazaroff's material is a far cry from the gentle comforts of childhood lullabies, or the strident yet doomed pleas of partisan songs. It is a sort of swearing granny, pulling down the trousers of politer and more polished Yiddish music: "down home, rough hewn, spontaneous, imperfect, and infinitely exciting" (Michael Alpert, liner notes). Kahn and friends treat it as such, mining it for its wit and energy without ever getting too smug. The Brothers are faithful to the Prince's originals, whilst at the same time managing to inject plenty of their own personality. This makes the recording more than a historical document, giving it instead an infectiously contemporary feel: a window on a lost Russian-American world which feels like it could still be happening, if only one knew which bar to drink in. This is a gang you want to join, a group of passionate yet unpredictable brothers you'd be tentatively proud to call your own. In between the singing itself, there is much happy shouting, whistling and laughter, and the music is performed with the same kind of heterophony (the same melody played by everyone, but not in exactly the same way) that characterises traditional instrumental klezmer performance. The disc is also structured around the multi-lingual play at which Kahn, Alpert and Korolenko excel, slipping easily between Yiddish, heavily-accented English (Brooklyn, Moscow… ) and Russian. This is more than just cleverness - such bi- or trilinguality remains a daily part of immigrant life. Nowadays, it makes the music simultaneously familiar and estranged. As Jeffrey Shandler points out in his discussion of "post-vernacular" Yiddish (the point at which simple communication is no longer the aim), translation becomes part of the performance. And indeed, these new renditions make the loop complete, through their frequent inclusion of sung versions of both the original - often pleasantly daft - printed Folkways English translations and the modern Brothers' own equally idiosyncratic new additions.

The majority of singing duties are taken by Kahn (who is also the record's producer) and Korolenko. They make a fine pair, Kahn's gritty passion - mostly in Yiddish - contrasting well with Korolenko's slightly creepy urbanity - usually in English. Michael Alpert lends his distinctive sophistication to three tunes, Bob Cohen provides vocals for one track, and fiddler Shulman-Ment even offers a line or two of Jewish New York-ese. Plus most numbers feature varying degrees of enthusiastic choruses from all. Instrumentally, the majority of songs are supported by Kahn on accordion, Shulman-Ment on fiddle and Cohen on mandolin or tzoura (small bouzouki, here re-spelled as tsuras, deliberately close to the Yiddish for "troubles"), augmented occasionally by Alpert's guitar and - for five tracks - Hampus Melin's klezmer poyk (marching drum and cymbal). If the bird whistles at first seem a little surprising, the liner notes remind us that one of the reasons that Al Jolson was able to cover up his breaking voice so speedily was that whistling was a fundamental part of the vaudeville repertoire.

The opening track, Vander Ich Mir Lustig (While I'm Happily Wandering) is a litany of bad luck, which sees the protagonist fall prey to the vicissitudes of Wall Street, freak weather, industrial disaster, diseased livestock and marital break-up. Despite this, he remains undiscouraged, "Singing a joyous tune/Whistling at the world", and supported by a vociferous chorus set to the melody of the Soviet tune Yablochko. It's a nicely self-aware take on the 'laughter through tears' Yiddish music cliché, whilst also reclaiming the Wandering Jew back from any antisemitic provenance. Tumbala Laika is a Yiddish chestnut remade here as both recognisable and weird. The Prince's rendition is a far more sensual, indulgent and narcoleptic affair than the better-known, coyly romantic version, and also benefits from the contemporary Brothers' self-consciously peculiar translation ("Radiantly the eyes of maidens / Beckoned and like stars were twinkling, / Then I felt enchanted and dreamy / As if of old wine I had been drink[l]ing"). The song's fantastically awkward scanning and near-random rhyming add a nice touch of the absurd, the fractional hiatus between the end of Korolenko's English verse and the group's Yiddish chorus almost like the pause after the punchline (before the laughter).

Ihr Fregt Mich Vos Ich Troier (You Ask Me Why I'm Mournful) is a lament to a lost wife, and the lost friend that she ran away with. A bluesy ode to vodka, Kahn's singing and Shulman-Ment's fiddle wrench every last drop of melodrama from the performance. Ultimately, however, such comically OTT self-indulgence reminds us this is a music-hall sadness, not the real thing - reinforced by the piece's origins as a Yiddish theatre song. Arum Dem Feier, a melody often treated delicately and reverentially by performers, here becomes one of those songs that just builds and builds, gathering irrepressible momentum along the way. The Brothers' rendition follows the Prince's original, moving from wordless nigun (chant) through group chorus, to a Russian waltz, gradually picking up speed until it is truly rocking by the end. The Freilachs medley which follows is rough, spirited, joyful (the meaning of 'freilachs') and impossible not to dance to. Pitched somewhere between a fully-formed arrangement and an 'anything-goes' session, it is like a Jewish wedding reimagined by The Ramones. Halfway through, Nazaroff's version of the well-known Yiddish trope "Yidl mitn fidl" ("little Jew with his fiddle") makes the first of several appearances here, usefully reminding us of the elastic boundaries of traditional material.

Maidlach Vie Blumen (Girls Are Like Flowers) is an ode to feminine charms in waltz time, based on the Russian folk song Din Din Din. Kahn and Korolenko's crooning gives it a slightly leery edge, treading a fine line between the raffish and the seedy - which is more-or-less the balance that the lyrics themselves strike. Der Koptzen (The Poor Man) is a rough-and-ready nursery rhyme of domestic strife, delivered slightly manically by Cohen (Zaelic Nazaroff). Alongside its near-demonic 'ha-ha-ha' refrain, the song also contains the disc's one original lyric, a Russian children's rhyme from Korolenko which the Brothers deem "too scatological" to translate. Fishalach (Little Fish) is the only true cover on the disc, rich in symbolist imagery of the sea, love, fishing and dreams. A slow, ponderous dance, it has a strongly Russian flavour. And although the piece has the feel of a folk song, it is in fact the original creation of Aliza Greenblatt, acclaimed Yiddish poet and Woody Guthrie's mother-in-law.

Oy Bin Ich A Mazeldicker Yid (Oh! I am a lucky Jew) is an ensemble tour-de-force, an unstoppable steam-engine benefitting from the addition of Berlin-based DJ and bandleader Yuriy Guzhy's vocals and the enthusiastic whistling of British clarinettist Merlin Shepherd. Echoing the tongue-in-cheek grin-through-adversity of the opening track, the tune is relentlessly upbeat despite the trials of demanding children, no money, long working days and a sobbing wife. Jake Shulman-Ment (Yankl Nazaroff) manages to rhyme "tired" with "riot" (say it with a Brooklyn accent), and the word "yid" gradually overlaps with the word "dude", calling to mind the nowadays largely imaginary Yiddish world, where: "it's totally normal to be a yid. It's not really a question of religious or ethnic identity" (liner notes). Underneath the ironic good humour, the tune is smarter than it lets on - just why is this Jew so lucky? What does he know?. It's a question which has spawned plenty of answers, not least Canadian 'whisky rabbi' Geoff Berner's Lucky Goddam Jew.

Tracks 10 & 11 are learnt from outtakes to the original Folkways session. Maidlid (Maiden Song) is a melody with a strong klezmer cast to it - indeed the first five notes form a phrase which opens many a freylekhs. The lyric's somewhat out-dated (acknowledged in the liner notes) image of woman as temptress/gold-digger is probably the one piece of the Prince's repertoire to truly show its age. The Brothers just about carry it off, although they don't exert themselves too much either, and it's worth noting that no English translations are sung here. Ich Flee (I Fly) is set to a well-known klezmer tune, known variously as Tants Yidelekh, Ma Yofus and Reb Dovidls Nign. Masquerading as a simple list of travel destinations, it is in fact a heroic and impossible chronicle, or as the liner notes put it: "a veritable anthem to epic diasporic restlessness and the transnationality which typifies not only the wandering 'yid' but the endless road of the troubadour". Covering a superhuman portion of the globe, and including many locations that no longer bear the same name, the song is a testament to Jewish migration couched in the romance of international travel, at a time when it still retained a pre-Easyjet allure.

The two penultimate tracks have their origins 25 years before the rest of the album, from two recordings that the Prince made for Columbia in 1928. The differences with the rest of the material are noteworthy. Lyrically and musically, the Prince's Russian roots are far more pronounced. Yiddel Mit Zein Fidel is a Russian march, delivered in fine style, mostly by Korolenko (Pasha Nazaroff). Its sprightly verse contrasts neatly with the tavern-like singalong of the chorus. It also contains my favourite two lines of the whole album, a couplet which sums up the irresistible and anarchic linguistic and musical patchwork that pervades the recording throughout: "On weddings and baptisms / And balls and circumcisms / This Yidl fiddles right into your heart".

Krasnoyarmeyskaya Pesn' (Red Army Song) is a curious addition. It was the B-side to Yiddel and has the definite feel of an afterthought. A march-like ballad set to accordion, fiddle and bird whistle, the song is a doggerel exultation of the Tsar's defeat at the hands of the Bolshevik revolutionaries. Consisting of six short verses of avowedly major key Proletarian heroism, the Brothers' English translation deliberately retains the original Russian text's anachronistic feel. The final offering is perhaps the oddest of all, and the only one which bears no direct relation to a Nazaroff recording. It is a once-through music box rendition of the first part of Hava Nagila, accompanied by vigorous bird whistles from Kahn. The track's raison d'être was the discovery of a promotional flyer for the original Folkways album, which urged readers to "Now sing along with the 'Prince'", and provided a bizarre transliterated version of the Hebrew lyrics to Hava Nagila in order to help them do so. This despite the fact that this song appears nowhere in Nazaroff's known recorded repertoire, and in fact stems from the nascent Hebrew-centric Israeli culture whose reinvention was the complement to Yiddish culture's decline. It is a happy confusion of language, provenance and tradition that makes a surprisingly fitting coda.

The extensive liner notes are an excellent complement to the music itself. Accepting the limits of factual information on both the Prince and his compositions, the Brothers instead opt for a mixture of cultural history, personal response and tongue-in-cheek self-analysis. Alongside the sharp self-deprecating wit of the track descriptions and their creatively faithful new translations, there are three longer pieces which offer both useful background and well-observed cultural insight. Writer Michael Wex (Milton Nazaroff) contributes an essay which tracks the nostalgic post-war assimilation of Yiddish musical culture, whist at the same time placing Nazaroff and his descendants as an appealingly subversive response to this assimilation. Similarly, singer Michael Alpert (Mishka Nazaroff) evokes the boardwalk communities of his Los Angeles youth, showing how American immigrant Yiddish life in fact persisted later and stronger than is generally supposed. And Daniel Kahn (Danik Nazaroff) gives a very personal account of the direct and visceral connection he felt upon first discovering Nazaroff's original recording. The disc therefore also stands as a vote for a culture's continued vibrancy, a proud testament to the fact that not everything was absorbed by mainstream American Jewish society.

The only negative is that, unless a lost Folkways session is miraculously uncovered, the Brothers have deliberately limited their potential material to the scarce resources bequeathed them by Nazaroff himself. Although in truth, this group of Yiddishist comrades embodies a performance aesthetic more than it represents a bounded repertoire, and I suspect that a team as energetic and musically irrepressible as this will have little trouble finding something similar to get their teeth - and bird whistles - into for the next recording.

Phil Alexander - 3.5.16

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |