There'll be glory, what a glory, praising Jesus ever more.

The Worlds of Charley Patton

Revenant 7-CD Album RVN-CD-212

US price $169.98. UK Retail Price, £119.99

| There'll be glory, what a glory, when we reach that other shore There'll be glory, what a glory, praising Jesus ever more. |

| Charley Patton (Paramount 12883) |

| "He was the B B King of his day. He was the man" |

| Gayle Wardlow |

Many years ago I used to watch a rather trite television series about a London daily newspaper. In one episode, a neophyte typesetter assembled a headline so large it could have doubled as scaffolding for the Eiffel tower. "Not that one, Son", said his world weary supervisor. "We're saving it for the second coming."

Well, to judge from what landed on my doorstep, I'd say the second coming has just arrived. This is not a release for the dabbler or the dilettante. It is not a toe in the water exercise for someone looking to broaden their musical horizons. If you are thinking of forking out one hundred and sixty nine dollars and ninety eight cents on a seven CD set of this or any other artist, you are going to be pretty damned committed. Therefore, this review will not concern itself with the usual questions of artistry and repertoire. Instead, it will take the assertion that Charley Patton was a consummate performer of the very first rank as read, and it will address two primary questions. 1. Does it justify the asking price? 2. What does it tell us about Patton that we don't know already? How far, in fact, does it get beneath those contradictory masks of Patton's; the clown and the sociopath?

Off with the motley, then, and I am here to tell you that Revenant have delivered some baby. Its volumetric displacement is in the order of 500 cubic inches; its written tracts easily exceed 100,000 words; and it tips my kitchen scales at just under six pounds. Pulling the innards out of the slipcase, one is left holding what looks like an old fashioned photograph album. It isn't. Revenant have resurrected the 78rpm record album, and modified it to suit their present needs. In the days before microgroove, the 78 album was used to accommodate works which were too long to sit on single records. Broadway musicals and large scale classical works were marketed thus. So, surprisingly, was the first publication of Woody Guthrie's Dustbowl Ballads. I cannot imagine that anyone at Paramount or Vocalion ever considered issuing Charley Patton in this format, but we'll let that pass.

Lift the album cover, and you will find a pea vine decorated wallet on the inside. There is nothing special about it, except that it holds a copy of John Fahey's old Studio Vista book on Patton. On the adjoining page, you will find a memorial to Fahey. He was one of the prime movers of this project, but sadly he died before his vision could be realised. Turn a page or so more and you come to the list of contents. This identifies five contributions by various authorities, plus track listings, plus appendices, but does not mention Fahey's book. Also, there are some notes by Bernard Klatzko, which sit in a slot at the back of the album. These are not listed either, nor is there any listing for the photographs and other illustrations, Finally, the contents give the wrong page numbers for two of the appendices.

The track listing does not appear until page 55, which makes it awkward if you're trying to locate individual tracks, or follow listings in other parts of the album. Also, I found the layout of the track list a little messy. That is mainly because all 110 entries, have been squeezed on to one page. However, you will find the tracks itemised in line by line format at the end of this article. Alternatively, you can go to http://www.johnfahey.com/RevenantDetails.htm, which is where I swiped the list from.

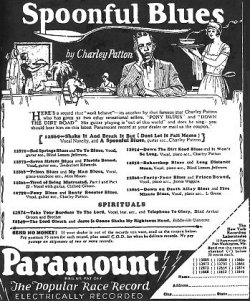

I ought to leave off discussing the hard copy side of the package, because I know that you are anxious to get to the CDs. To do so, however, you need to negotiate ten pages of record label stickers, and six pages of adverts. The latter are copies of Paramount's famous inserts in the Chicago Defender, and they are such a core element of blues iconography that every blues fan will know them already. Nevertheless, the present reproductions are in a larger and clearer format than any I have seen before, and they are vivid testimony as to just how little race record companies knew or understood, or cared about what they were dealing with. It's not surprising that Paramount missed the sexual connotations of Pony blues; or that they failed to realise that Pea Vine Blues referred to a railroad, rather than some insignificant part of the local agricultural economy; or that they failed to notice that Dirt Road Blues contained nought but a passing reference to a road, and a dark one at that. But their advert for Spoonful Blues, which is generally taken to be about cocaine, is too incongruous for words. It shows a fed up looking Charley Patton, sitting in a plush white restaurant, being served by a white waitress. Even with Patton's Caucasian features, I don't think so! (The illustration here does nothing to convey the clarity of Revenant's reproductions, by the way.)

I ought to leave off discussing the hard copy side of the package, because I know that you are anxious to get to the CDs. To do so, however, you need to negotiate ten pages of record label stickers, and six pages of adverts. The latter are copies of Paramount's famous inserts in the Chicago Defender, and they are such a core element of blues iconography that every blues fan will know them already. Nevertheless, the present reproductions are in a larger and clearer format than any I have seen before, and they are vivid testimony as to just how little race record companies knew or understood, or cared about what they were dealing with. It's not surprising that Paramount missed the sexual connotations of Pony blues; or that they failed to realise that Pea Vine Blues referred to a railroad, rather than some insignificant part of the local agricultural economy; or that they failed to notice that Dirt Road Blues contained nought but a passing reference to a road, and a dark one at that. But their advert for Spoonful Blues, which is generally taken to be about cocaine, is too incongruous for words. It shows a fed up looking Charley Patton, sitting in a plush white restaurant, being served by a white waitress. Even with Patton's Caucasian features, I don't think so! (The illustration here does nothing to convey the clarity of Revenant's reproductions, by the way.)

The adverts are followed by seven 10" record sleeves. Each contains a black cardboard insert, which has been made up to look like a Charley Patton 78. Don't try and play them, for they are merely the CD holders. We have reached the motherlode, but not the end of the surprises. The CDs have likewise been coloured black, and labelled to resemble miniature shellac discs. By now I was beginning to wonder where Revenant had stashed the wind up gramophone, but fear not.  All you need is a conventional CD player. It will break Revenant's heart for me to say this, but I immediately took the discs out of their sleeves and placed them in slimline jewel cases. That way, the sounds are accessible, the album doesn't get knocked about every time I want to listen to Charley Patton, and I don't end up with tennis elbow.

All you need is a conventional CD player. It will break Revenant's heart for me to say this, but I immediately took the discs out of their sleeves and placed them in slimline jewel cases. That way, the sounds are accessible, the album doesn't get knocked about every time I want to listen to Charley Patton, and I don't end up with tennis elbow.

You may be wondering how Charley Patton's output of fifty-odd tracks came to be stretched over seven CDs. It isn't. Only five of the discs feature Patton. The remaining two are concerned with people who were connected with him in various ways. Also, the five Patton discs include a fair amount of material by other artists. More of that anon. In the meantime, it is probably fair to assume that this is the most comprehensive Charley Patton anthology which has ever been issued. It embraces all Patton's own releases, plus his accompaniments, plus all the non-issued material which it has been possible to recover. It is a pity therefore that the publicity could not have been more careful in telling us that the set contains all Charley's issued and unissued recordings. To be entirely accurate, the word extant should have been included.

Looking at the programming of the five Patton CDs, I initially thought Revenant had organised the discs to replicate his five recording sessions. That sounds a great idea although, even with the non-Patton material included, the running times of the first four discs are somewhat on the short side. Also, the idea of dovetailing session to CD, if that's what it was, runs out of steam before the cycle is complete. The running order of Patton's sessions, and the CD playing times, complete with extra artists, looks like this:

| Session No | CD No | Location | Date | Playing Time |

| 1 | 1 | Richmond, Indiana | June 1929 | 55:59 |

| 2 | 2 | Grafton, Wisconsin | ca. October 1929 | 55:17 |

| 3 | 3 | Grafton, Wisconsin | ca. October 1929 | 42:02 |

| 4 | 4 | Grafton, Wisconsin | June 1930 | 50:10 |

| 4 (Remainder) 5 | 5 5 | Grafton, Wisconsin New York | June 1930 January/February 1934 | 75:18 |

Discs 6 and 7 measure 73:26 and 55:33. However, being ancillary to the main story, they will be dealt with later.

Which brings me to the problem of similitude; namely how do I appraise this product, when there is nothing on the market to compare it with? It is true that Charley Patton is well represented in conventional CD anthologies on Yazoo, Document and Catfish, but these are considerably less expensive than the Revenant. The Yazoo and the Document would, I imagine, set you back around thirty pounds apiece, whilst the Catfish is in the current Red Lick catalogue at just £14.25! In these days of impending recession, that is something you may wish to think about. However, I do not find Yazoo or Document or Catfish particularly impressive in terms of remastering or documentation or packaging. With the present set, I have already expressed my amazement over the last two features, and the acknowledgements tell us that audio restoration has been carried out by David Glasser of Airshow Mastering, Boulder, Colorado. Comparison with various Patton vinyl reissues, principally Founder of the Delta Blues (Yazoo L-1020), shows that he has done an excellent job. We cannot expect miracles. However, on all but the worst quality tracks, the sound is comparatively full and clear, and the surface noise is pushed well to the background.

"A lot of Charley's words ... you can be sitting right under him ... you can't hardly understand him." Son House.

My calculated guess, then, is that the sound quality of the present anthology outstrips any of its rivals. However, first class remastering does not guarantee first class listening, and Charley Patton fans have three proverbial crosses to bear. The first is Patton's diction. His words were frequently slurred and growled to the point of incomprehensibility, and his voice sounds to me as though it was produced by constricting the throat muscles and forcing the words through at considerable volume.

Secondly, there is an endemic problem facing anyone who tries to clean up pre-depression blues or ethnic or old-timey records; namely, that the technician has to work from scratched and battered secondhand shellac copies. Ergo: the quality can vary between bad and horrendous, and - Mr Glasser's efforts notwithstanding - this set has several tracks where the music vanishes under a heap of crackle.

The third problem lies with Patton's choice of record company. The bulk, and best, of his work was done for Paramount. Paramount had a fabulous catalogue, which embraced some of the greatest names in 1920's Black music, but their productions were a byword for excessive surface noise and appalling sound. That echoes the difficulties of a small company in a fierce market, but precisely how size affected quality is open to question. According to John Fahey, the problem was one of resources, in that Paramount could not afford the recording equipment of the larger companies. Before questioning this, it is worth observing that Paramount, who were based at Grafton, Wisconsin, made a lot of their recordings at the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana. The first Patton session took place at Richmond, and the sound there is every bit as bad as his later ones at Grafton. Since Gennett was another small company, we might conclude that both firms were similarly strapped for decent tackle. I would have thought, though, that the market for studio sound equipment was very restricted, and there would in consequence have been a limited range to choose from. If so, Paramount and Gennett would have been forced to use the same apparatus everyone else was using. However, irrespective of whether market economics affected the choice of studio equipment, they certainly affected the availability of raw materials. That is because the larger companies were able to use their financial muscle to buy up all the good quality shellac. As a result, the smaller firms were forced to make do with inferior shellac. And inferior shellac equals pluperfect awful sound.

The tracks from Patton's final session are aurally much more acceptable; their quality here serving as a limited but useful evaluation of David Glasser's remastering. It's a long story, but that final session was cut for Vocalion, whose catalogue ended up as part of the holdings of Columbia Records. As a result, Columbia issued several Patton Vocalions in their Roots 'n Blues series, and Revenant's sound is a distinct notch or two behind Columbia's.

That, however, is recommendation, not criticism. As every fan will tell you, the Patton on the Vocalions is not the Patton of old. They were recorded a few months before he died of heart disease, and he sounds much more subdued here than on the Paramount sessions. Even so, comparing Revenant's remastered Stone Pony Blues, with the one on Columbia (468992), is an edifying exercise. Patton sounds so much more alive on the Revenant that I wondered if a different take had been used. It hasn't, or at any rate the Vocalion matrix numbers quoted by both companies are identical. Checks for Revenue Man Blues (4672452) and Jersey Bull Blues (CK 47914) revealed a similar, though less dramatic contrast. That is possibly because, of the three titles, Stone Pony is the only one on which Columbia used the CEDAR remastering process. CEDAR was something of a pioneer in the field of audio restoration, and it initially came in for considerable criticism from 78 buffs. After hearing the way Stone Pony ought to sound, I am beginning to think they had a point.

Up to now, I have not brought Patton's musical associates into the picture, because whoever idolises Charley Patton will not need telling about Son House, Willie Brown, Louise Johnson, Son Sims, or Bertha Lee. In a complete anthology, such as this, there is an undeniable case for including recordings of other people, where the main subject acts as accompanist.

However, this anthology contains quite a wad of material, which does not feature Patton, and I find myself expressing reservations about its inclusion. Revenant's covering letter tells me that John Fahey originally intended the project as a Patton centred musical survey of the 'pre-Robert Johnson Delta'. However, neither the slipcase nor the album give any clue about this. Nor do they explicate the fact that Patton is absent from many of the tracks. Indeed, the only comment I could find came in the third paragraph of the publicity handout, where it describes the package as a '7-CD primer on Mississippi blues'.

Thus, when I saw four Walter Hawkins recordings in the tracklist, I assumed that Patton must have been in there with a second guitar. That left me wondering why the notes to Saydisc Bluesmaster MSE 202 do not mention one, and why my ears had failed to pick it up. There is no second guitar. These are solo performances, and Revenant's justification for including them is that they were made on the same day and location as Patton's debut session in Richmond, Indiana. Also, someone speaks on one of the tracks. The interjection could have come from Patton, but the odds suggest otherwise. I am a fan of Walter Hawkins, and regard him as a neglected artist, whose name could do with much wider exposure. Nevertheless, I began to feel like someone who has hired a taxi he can't afford, and is nervously watching the meter racing off with all his cash.

There are also eight tracks featuring the Delta Big Four and these are likewise devoid of Charley Patton. This group was news to me and none of the blues reissue companies, whose websites I checked, seem to have them in catalogue. Also, a trawl through various textbooks yielded just one piece of information. Paul Oliver's Blues Off The Record![]() 2 claims that John Lee Hooker once sang with them. Acres of diamonds? A honeyed field of hidden treasures? I'm afraid not. The tracks in question were cut in 1930, before Hooker began singing with the group. I can only describe them as plodding and sombre, and following in the rather dreary tradition of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Moreover, the reasons for their inclusion in this set seem not much less slender than those for Walter Hawkins. A short note in the song transcriptions tells us that the Big Four sang in the same choir as Patton's wife, that Patton recommended the group to Paramount Records, and that the group's leader once drove Patton, Son House and Willie Brown to the Paramount studio.

2 claims that John Lee Hooker once sang with them. Acres of diamonds? A honeyed field of hidden treasures? I'm afraid not. The tracks in question were cut in 1930, before Hooker began singing with the group. I can only describe them as plodding and sombre, and following in the rather dreary tradition of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Moreover, the reasons for their inclusion in this set seem not much less slender than those for Walter Hawkins. A short note in the song transcriptions tells us that the Big Four sang in the same choir as Patton's wife, that Patton recommended the group to Paramount Records, and that the group's leader once drove Patton, Son House and Willie Brown to the Paramount studio.

In any event, if your tastes in sanctified singing were honed on some of the great singing preachers, or guitar evangelists, I doubt The Delta Big Four will do much to entice you to the fold. As if to underline that point, they are on the same CD as the Patton Vocalions. That means they vie with a pair of religious sides, which Charley cut for that company with Bertha Lee Patton. Audially, these are perhaps the worst of the Patton Vocalions, but their music is wonderful and timeless. I would not use either adjective about The Delta Big Four.

The quartet of recordings by Edith North Johnson is almost as Pattonless, although there is a guitarist on one track, and it might be Patton. I must say I found these tracks much more agreeable, and she also seems currently absent from reissue catalogues. In a more affordable package, I would have regarded her as a welcome bonus.

Edith Johnson came from Missouri and Walter Hawkins' birthplace is as far as I am aware still unknown.![]() 3 In neither case do I see much point in including them in a survey of the pre-Robert Johnson Delta. We are though on safer ground with the tracks from Willie Brown, Son Sims, Son House and Louise Johnson, although the House and Brown tracks do not have accompaniments from Patton. To top it all, there are two test pressings of H C Speir, Paramount's local agent, reading newspaper articles. They are so incomprehensible that Revenant have not transcribed them, and I could not decipher them. There is no questioning Speir's place in blues history, but I do not see how two tracks of him reading newspaper articles adds to our understanding or enjoyment of Charley Patton.

3 In neither case do I see much point in including them in a survey of the pre-Robert Johnson Delta. We are though on safer ground with the tracks from Willie Brown, Son Sims, Son House and Louise Johnson, although the House and Brown tracks do not have accompaniments from Patton. To top it all, there are two test pressings of H C Speir, Paramount's local agent, reading newspaper articles. They are so incomprehensible that Revenant have not transcribed them, and I could not decipher them. There is no questioning Speir's place in blues history, but I do not see how two tracks of him reading newspaper articles adds to our understanding or enjoyment of Charley Patton.

Unless I've miscounted, of the 94 tracks, which comprise the five Patton discs, there are no less than 27 in which the man plays no musical part. I applaud Revenant's desires to place Charley Patton's recording career in some sort of socio/musical framework. Also, some the material they have used - and I'm thinking particularly of the House and Brown tracks - is staggering; and it is all the more so for having been remastered in Boulder, Colorado. Nevertheless, I feel the point should have been made much clearer.

The last two CDs are identified as Charley's Orbit, which means they feature songs and performers who were connected with Patton in some way. Of these, disc 6 consists of singers whom he either inspired, or who recorded songs with Patton connections. The track list is a mix of the obscure and the eminent and is drawn partly from commercial sources and partly from Library of Congress recordings. Familiar names include Ma Rainey, Tommy Johnson, Bukka White, Big Joe Williams and Howling Wolf. However, it's not just the big guns who make this disc worth prizing, for there are sterling performances from all concerned. I was particularly taken with Walter Rhodes and his accordion accompanied Crowing Rooster. Recently, I reviewed Rounder's Deep River of Song: Alabama for these columns, and expressed my surprise at finding an accordion playing blues singer amongst the credits. Isn't that typical? You wait around for forty years and then two arrive together.

Even so, I wondered if I shouldn't object to this disc also, especially as the connections with Patton are, in some cases, decidedly tenuous. However, I feel that would be churlish, for the disc is an absolute cracker and some of its goodies are extremely rare. If Revenant can produce anthologies as good as this, I'm glad they're in the reissue business.

The final disc consists of interviews with Howling Wolf, Booker Miller, H C Speir and Roebuck Staples. Being a huge fan of the Wolf, I was particularly looking forward to his contribution, but it only lasts for two minutes. Well, that is two minutes more than I've ever heard him interviewed before. Unfortunately, although the tracklisting tells us that the discourse was made by Pete Welding, around 1967, I could find nothing to indicate whether the rest of the interview has ever been published.

The Wolf extract, short as it is, sets standards of listenabilty which the Miller completely fails to follow. Miller is audible enough, but the recording sounds as if it has been done on a cheap machine under adverse conditions. There is a desperately loud background hiss, which made me wonder if Revenant hadn't saved a bit on the cost of remastering. Also, there are frequent interruptions as the mike goes on and off, and a large part of the conversation is played out against a barrage of Charley Patton records. Miller has some valuable reminiscences, and it's interesting to hear him demonstrate Patton's guitar style without the Paramount crackle. For that matter, he turns out to be an interesting singer, with a style which at times reminded me of Mississippi John Hurt. But a more severe pruning would have been in order.

Miller's contribution was recorded by Gayle Wardlow, as was H C Speir's, and both were done around the same time (1968-9). The Speir is also noisy in places, but the listening quality is generally a lot better. There is some interesting stuff, as Speir relates his involvement with Columbia and Paramount Records and the other companies he scouted for. However, anyone expecting an interview on Charley Patton should note, it is over five minutes into the conversation before he gets a mention. Overall, I found the Speir interview a fascinating piece of oral history. Unlike certain other entrepreneurs of the race record industry, he comes across as genuinely interested in the music, and genuinely sympathetic towards Black people. It makes one wonder how much Patton's decision to record for Paramount was influenced by their having Speir as talent scout.

Roaring background noise returns with the final interview. This time it's Chris Strachwitz interviewing Roebuck Staples. Like the Wolf, it's very short, slightly under two minutes, and not a lot comes out of it. The pity is that Strachwitz didn't use the opportunity to ask the sanctified Mr Staples about Patton's religion.

Taken together, the interviews are a bit of a hotch potch, and they certainly don't add up to a coherent oral history of Charley Patton. That is to be expected, for they were never intended to be one. Yet there is such a wealth of information here. Listen to Speir on the hit and miss business of race recording for instance, or his observations on the nature of the blues. As indication of how useful some of the minutiae might be, there is a piece where Wardlow reminds Speir, that he was the man who persuaded Victor to record an Indian fiddle band. Incongruous as that may seem, there was such an outfit - Big Chief Henry's Indian Band - who made a single record for Victor in Dallas in 1929. I'd have thought Dallas a little off Speir's beat. But could this be the same crew?![]() 4

4

These interviews contain so much raw material that it's a pity Revenant decided not to transcribe them. Their decision is understandable, because it would have swelled the album considerably. However, one wonders if they could have taken a leaf out of Musical Traditions' book, and published the transcribed interviews on the Internet.![]() 5

5

Let us take stock of where we're at. So far I have notched up several reservations. They concern the price and packaging, a few minor editorial problems, and a lot of superfluous recordings. If these are discounted, what is left emerges as the best and most comprehensive and most listenable Patton anthology which is ever likely to appear on the market. Whether it is the one to go for, when its cheapest rival can be got for about an eighth of the price, is a different question.

However, the written contributions are another story, for they knock all the other Patton releases off the shelf. With such a concord of riches, exhaustive abstraction is not going to be an option. However, I shall discuss general outlines and flag up significant points of dis/agreement on my part. Listed individually, the contributions are:

Prepare for a long and frustrating read. Apart from the difficulties of manoeuvring six pounds of book, the album contributions have been printed in coloured ink on coloured paper and are in places very difficult to decipher. I must say that the good people at Revenant were extremely helpful in straightening out some of the difficulties I encountered. Even so, a more legible colour mix would have saved my eyesight, and prevented those difficulties from arising.

However, as I mentioned earlier, the first two documents are free-standing facsimiles, and are therefore in black and white. Of these, the source of the Klatzko is not explicated until the very end of his notes. It is for the most part an interesting, if frenetic, memoir of the efforts of Bernard Klatzko and Gayle Wardlow, to glean some first hand information from people who remembered Patton. As David Evans observes, it is virtually unique among early Patton commentaries, in that it sees the performer's style as a consequence of personal outrage. Moreover, it attributes this outrage to Patton's relegation to Negro status by the Mississippi caste system. Unfortunately, Klatzko's style is breathless and dated, and the notes possess their share of typos, and there are one or two minor errors. Overall, it is best regarded as a keepsake, and a reminder of 1960s reissue standards.

The Fahey is much better. It is essentially a musical study, which includes a biography and a textual analysis; and the longest definition of a mode I have ever encountered! In view of its age and brevity there is little point in dissecting the document, especially when Fahey revisits some of his thoughts in the album. There were, though, one or two places where he trod on a couple of cerebral corns of mine.

First of all, in a fairly lengthy introduction, he discusses the respective roles of folk song collectors and race record companies. His findings, if I have interpreted him correctly, are that collectors and record companies alike acted as mediators of that which they harvested. Therefore, there is no practical difference between the two, and the efforts of both parties are equally valid. I have to disagree, and I do not think the evidence he presents supports his own case. Both groups misrepresented the tradition, but they were steered by different motives. Consequently, their misrepresentations took different forms. Moreover, collectors generally had little bearing on the traditions they collected, but the commercial forces unleashed by the record companies often altered those traditions beyond all recognition.

Also, I was taken with Fahey's discussion of Patton's texts, and I was swayed by his argument that Patton pulls an emotional consistency out of seemingly incoherent verse patterns. Much is made in several of the contributions to this package, of the apparent incoherence of Patton's verses. This surprises me, or at any rate it surprises me that Patton should have been singled out, for I have always regarded the blues in general as one of the homes of the incoherent text. In any event, it might have been helpful if the contributors had taken some time out to investigate textual incoherence in other oral traditions. Examples can be found on a global scale, and experience shows that they usually exist for one of two reasons; either where the singer wants to establish a mood, rather than to retail a narrative; or where the song has some operative intent. E.G., to accompany dancing. I suspect that both these models apply to Patton's song structuring.

In point of fact, Fahey does display an awareness of other music cultures, and he sees in Patton's versifying, an 'extreme case of oral-formulaic creativity'. Unfortunately, though, I do not think this can be substantiated. The oral-formulaic theory was devised to explain the techniques used in performing Serbian epics.![]() 6

6

It argues that epic singers, whilst narrating largely improvised narratives of structurally coherent stories, sporadically insert standardised pieces of text into their performances. These are used as aids to improvisation and elaboration. That is, they take the strain off continuous composition, and enable the singer to tailor the narrative according to his perception of audience demands. By momentarily going on autopilot, as it were, the singer's mind is freed up to think what part of the story to throw in next, how best to elaborate it, and how the audience is likely to respond. Patton's performances do not tell a story and they do not rely on formulas. From Fahey's description, Patton's style of improvisation sounds to me more like a scissors and paste operation; i.e. he seems to have carried a large store of pre-composed verses in his head, and strung them together ad lib.

Incidentally, Fahey's book contains the Paramount adverts, plus a large number of transcriptions, and thus prefigures much of what appears in the album. Nevertheless, the album transcriptions are comprehensive and in CD running order. You will be glad of them.

On that note, we will delve into the album. Dick Spottswood's contribution is short, and largely given over to discussing the financial difficulties of Paramount Records. These, we are told, initially made Patton an interesting prospect for Paramount, but subsequently prevented the company from capitalising on his record sale potential. As a result, Patton's records never achieved the circulation they deserved, and he has languished in obscurity ever since. Meanwhile the world applauds the younger, Patton influenced, Robert Johnson. Discussions of the disparate popularity of the two performers are offered in two separate articles and in the publicity. Indeed, the injustice of their comparative fame appears to be a primary reason for this release. Therefore, I need to take some time out to deal with the matter, and the supporting arguments can be summarised thus. As well as the problems of an obscure, financially troubled label, and the fact that Patton was recorded on the eve of the great depression, we are reminded that Johnson was recorded later than Patton, by a bigger firm. Hence, his recordings enjoyed better sound. Also, the manner of Johnson's death - poisoning at the hands of a jealous girlfriend - has acquired a romantic notoriety; as has the famous story of his selling his soul to the devil. To these we can add Patton's unsavoury reputation, one or two misleading film scripts, and Johnson's lionisation by pop icons such as Dylan, The Stones and Eric Clapton.

These are valid points and they are worth raising. However, I'm wondering why Revenant singled out Robert Johnson, rather than, say, Big Joe Williams or Son House, or any of the other Patton acolytes who subsequently achieved greater fame.

Also, Revenant's publicity is significantly off the wall, describing Johnson's exaltation as 'historical revisionism', and announcing that Patton was 'kingpin of Delta bluesmen' when Johnson was still in short pants. There is no doubting Patton's historic importance. He was in on the ground floor, and he forged a performance style which would eventually reverberate around the world. However, to regard Charley Patton as 'the best there ever was' is to hold an opinion. To regard Robert Johnson in similar light is to hold an alternative opinion. Moreover, the implication that Patton somehow diminishes Johnson's importance because he was around before Johnson, is nonsense. Mozart was the kingpin of Vienna when Beethoven was still wearing juvenile leiderhosen. That Beethoven built on what Mozart created does not diminish the greatness of either composer.

I agree that Patton has had a hard time at the hands of legacy builders, and I fully concur with Revenant's efforts to restore his name. However, some of this sounds like juvenile carping of the Cliff Richard vs Elvis Presley variety, which used to enliven my adolescence. I can only say that a world which recognised both Patton and Johnson as great artists and important ground breakers would be a mighty fine place.

In any event, the bit about Paramount's financial difficulties only tells half the story. Indeed, I'm left wondering why it was that the entrepreneurial Charley Patton left it until 1929 to enter the recording studio. Granted, the record companies explored the Delta later than certain other centres of blues activity, but did Patton make any earlier attempts to explore the record companies? Were his efforts thwarted by unimaginative producers? Or did he find live performances a more lucrative source of income than recording? Could it be that he did not trust white owned record companies? Mayo Williams, Paramount's Black record executive had moved to Vocalion by 1929, and played no part in securing his services. Nevertheless, a company which had recently employed a Negro in such an exalted position would doubtless have gone down big with Patton.

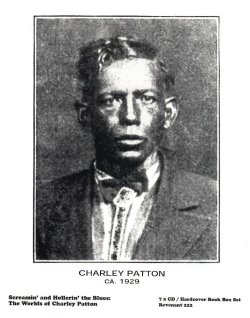

This point is exemplified in the next contribution, where David Evans draws a fascinating assessment of Patton's character, and correlates this with his repertoire and performance style. Marshalling a considerable body of biographical and family evidence, Evans questions the widely held view of Patton as performing clown and sociopathic womaniser, drinker, wife beater and idler.  He begins by arguing that the Pattons, being light skinned, did not regard themselves as Black, and they rejected the Negro status which the Mississippi segregation laws had recently accorded them. They were successful in business and, as far as was possible in the Deep South, they were upwardly socially mobile. In discussing the effects of segregation on the Pattons, Evans makes a passing observation, which could perhaps have been drawn out a little more. It is that racial barriers were hardening during the time Charley Patton was growing up. I assume he does not mean that the South became intrinsically any more racist during this period. Rather, I would take it that the segregation laws coalesced what had previously been a multi-graded society, into a two tier structure, with people of mixed ethnicity placed in the lower segment.

He begins by arguing that the Pattons, being light skinned, did not regard themselves as Black, and they rejected the Negro status which the Mississippi segregation laws had recently accorded them. They were successful in business and, as far as was possible in the Deep South, they were upwardly socially mobile. In discussing the effects of segregation on the Pattons, Evans makes a passing observation, which could perhaps have been drawn out a little more. It is that racial barriers were hardening during the time Charley Patton was growing up. I assume he does not mean that the South became intrinsically any more racist during this period. Rather, I would take it that the segregation laws coalesced what had previously been a multi-graded society, into a two tier structure, with people of mixed ethnicity placed in the lower segment.![]() 7

7

In this changing scenario, it is possible to see how easily a family like the Pattons would have jarred certain elements of the white population; and how much having to kow-tow to that population would have jarred the Pattons. Incidentally, Evans also scotches the widely held belief that Patton was illiterate. In doing so, he may have shed a little more light on Patton's ambiguous racial status.

The story of Patton's illiteracy is something originated with Son House, and he appears to have had good reason for believing it. Indeed, it is a matter of record that Patton signed his wedding certificate with a X, and Evans feels this was probably in response to the clerk's request for him to make his mark. If so, we may assume that the clerk was White and racist. We may also assume that he either took it for granted that Patton was illiterate, or else used a presumption of illiteracy as a means of asserting his racial and social superiority over Patton.

Faced with such an assertion, would Patton have feigned illiteracy as an accommodation strategy? Did he act illiterate to stay out of trouble, and did he likewise act Black to stay out of trouble? By teasing out these sorts of questions, we catch just an inkling of the anger he must have been keeping down. We may also begin to see that extraordinary singing style as a function of suppressed rage.![]() 8

8

"I've been working for my pay for a mighty long time. How come he still calls me boy?" Harry Belafonte![]() 9

9

Performance style as a function of rage is the hypothesis which David Evans puts forward. Substantively, I agree, although I feel that the hypothesis requires a little qualification; as will shortly become apparent. In the meantime, I'd like to observe that suppression of rage must have been an accommodation strategy for many a Deep South Negro. The caste system deprived Black people of the material means of comfortable life, and it deprived them of jural status. It treated them as children, and heavily deprived children at that. But Mister Charley Patton's need to suppress rage, stemming as it did from unjust relegation, may have been more deeply ingrained than most. If so, Patton starts to emerge as a catalyst; i.e. in turning his own anger to song, he became a stylistic model for other singers who were experiencing a similar need to diffuse their repression.![]() 10

10

David Evans next turns his attention to the question of Patton's character, and finds the evidence for sociopathic tendencies no less wanting than that for his alleged illiteracy. The picture he draws is convincing and well thought out, and Patton emerges as a reasonably balanced personality. All well and good, but should questions of character impinge on our enjoyment of music?

I would say not, or at any rate, it shouldn't as far as we are able to objectify musical appreciation. Nevertheless, the artist's personality enters into the argument, because what the artist feels is what the artist creates. It is for this reason that Evans spends a considerable part of his essay discussing Patton's composing technique, and examining his recorded repertoire. There is some fascinating stuff here, for Evans is delving into an area of blues scholarship which has been much observed and lip serviced, but seldom exhaustively discussed; namely how the performer uses the blues as a medium of personal expression. Despite the title, what the article doesn't do is discuss Patton's presumed role as spokesperson for his people. Yes, Patton's song on the 1927 Mississippi flood receives detailed examination, as are his seethings about white oppression, and there is his song about the 1922 Chicago railroad strike. But does that make him conscience or reporter? Personally, I doubt that Patton was either clown or conscience. He was an entertainer, pure and simple. If people wanted him to play the guitar behind his back, he would oblige. If people wanted songs of social import, he was ready and able. If people wanted songs about local worthies, they only had to ask. There are long traditions of news reporting and praise singing among professional musical entertainers in Europe and West Africa. It seems to me that these two traditions found a sort of convergence in Charley Patton. Yet Conscience of the Delta is perhaps the most incisive and thoughtful commentary I have come across on any traditional musician anywhere. We could do with many more like it, and I urge you to read this one.![]() 11

11

John Fahey's reconsideration of Patton does not follow Evans' article, but the two pieces share a lot of common ground. Besides acknowledging the importance of Evans' contribution - and incidentally treating us to a cogent discussion of Patton's musicianship - Fahey devotes a good swathe of his script to replying to Evans' criticisms of his earlier book. Moreover, like Evans, he is concerned to get at the 'real' Charley Patton. He is, though, less worried about stripping away the myths of Patton's behaviour, than with getting inside the mind of the man. I honestly do not know to what extent he may have succeeded, for Fahey's piece is in places extremely badly written. It is also opinionated, there are several irrelevant asides and it could have been better organised. To boot, it steered me into areas of intellectual discourse I either know nothing about, or have not touched these thirty years.

First of all, it emerges that Fahey possessed an interest in Freudian psychology, and he draws on his own experience of psychoanalysis to examine Patton's character. Fahey offers two propositions to account for the perturbation in Patton's songs. Firstly, we learn that Patton's marrying eight wives apparently stemmed from an unsatisfied quest for maternal compensation. That is, he kept seeking characteristics, which he originally identified with his mother, in the various women he met and married. As a consequence, he seems to have led a life of incessant unsatisfaction, until his final and successful marriage with Bertha Lee Patton; at which point a lot of the angst disappeared from his work.

Also, we learn that Patton was haunted by jinxes and demons and forces which seem bound up with his persona, but which were outside his control. He links these forces to Patton's all too evident obsession with death. I am not able to dissect what he says, but it may be as well that he did not carry his analysis too far. First of all, he was writing as a layman, rather than a specialist. Equally, I would have thought that we do not know enough about Patton's life to make meaningful pronunciations on his psychology.

"Sometimes I sing the blues when I know I should be praying". T Bone Walker![]() 12

12

Fahey next considers the part which religion might have played in Patton's singing. He asks how did the hard living, sinful Charley Patton reconcile his life style with the many sanctified pieces he sang, and with his religious family upbringing. Again, the ice appears rather thin, for the discussion seems based on a single conversation with the Rev Rubin Lacey. In any event, Fahey takes Lacey's comments as evidence that Patton was influenced by Lutheran doctrine. That is, he believed that salvation comes not from following the word of God, but by conversion, and by the recognition of Christ as the bearer of the sins of all humanity. Once you have reached that state of grace, the theology goes, there is no changing it. Consequently, you can sin all you want and you will still go to heaven.

Again, lack of knowledge places me at a disadvantage, but Fahey's line of reasoning seems to reflect attitudes towards the blues as they used to exist among Black people. These were, that the blues is a sinful medium; that good living folk should not sing or listen to the blues; and that blues singers should not sing religious songs for fear of contaminating them. It is an interesting application of Durkheim's famous dictum of the dichotomy between the sacred and profane; i.e. the continuing sanctity of things which are held to be sacred necessitates their inviolable isolation from the things which are deemed profane.![]() 13

13

This dichotomy is something which Fahey seems to recognise, for he argues that the majority of blues are an inversion, rather than a subversion of the religious message. That is, religion teaches us that the good go to heaven, while the blues teaches us that the bad go wrong. Therefore, the blues preserves the religious message inviolate and hence, there is no inherent evil in the medium. The profanity lies with the singer, rather than with the song, for the singer's unredeemed bad living ways are the personification of the evil which the song merely depicts. Logically, therefore, Patton felt exempted from the censure shown towards other blues singers. He was saved. Therefore, he was not profane.

It is a neat theory, but we should remember that Patton belonged to an earlier generation of entertainer than the blues singer proper. He was a songster, and he was by no means the only songster to include a fair number of religious pieces in his repertoire. It seems possible to me therefore that Patton's performance attitudes were moulded before the sacred/profane dichotomy had crystallised in Southern Black consciousness.

Nevertheless, Fahey's ruminations caused me to question my earlier accreditation of Patton's singing as a straightforward function of rage. Listening to him in the light of these comments, I was struck by how much his style resembles that of a singing preacher. This is not a new line of thought, for Fahey clearly thinks the man was influenced by religious singing and he makes some thought provoking comments on the content of Patton's religious songs. However, remembering that Patton was a showman, could his act have been a functionally secular replication of religious ecstasy?

I think it could, but I do not feel that possibility undermines our previous theory. Indeed, all this set me wondering whether the exuberant behaviour in Black religious ceremony, might have been an outlet for bottled up anger. We have blundered our way into functionalist theories of religion, which normally argue the existence of religion in terms of the reification of social norms, and of the normative integration of the individual within the accepted social order. That is because functionalists see religion in terms of its contribution towards the stabilisation of society, and the consequent integration of its members within the accepted social order. However, Deep South society was not so much integrated as fractured along racial lines. Moreover, its peculiar structure rested on the fact that the oppressors systematically denied the oppressed the means of vocalisation of their oppression. I mentioned suppression of rage earlier as an accommodation strategy among Black people. I also mentioned that Black people were treated as jural minors. That is because the social structure of the American South required intelligent, dignified, adult human beings to adopt the role of the childlike 'happy smiling coon', in the presence of Whites.![]() 14 In the land of the lynch mob, kow-towing to the White populace was not so much an accommodation strategy as a survival strategy. Negroes who tried to buck the system could easily find themselves strung up on the end of a rope. Is it not logical therefore that Black people, forced to suppress their feelings whilst in Mister Charlie's orbit, would let it rip inside the church; in a world unknown to white people? Oppression and racism are concepts which I find utterly odious, and I trust all who read these words will share my disdain. However, if we step outside of our personal values, we can begin to understand how the Black church in the American South contributed towards the stabilisation of an inherently unequal society, and to the perpetuation of unequal social norms, and to the safety of its own members. Religious expression existed as a safety valve. It was a way of syphoning off a discontent which would have been too dangerous to express in any other way.

14 In the land of the lynch mob, kow-towing to the White populace was not so much an accommodation strategy as a survival strategy. Negroes who tried to buck the system could easily find themselves strung up on the end of a rope. Is it not logical therefore that Black people, forced to suppress their feelings whilst in Mister Charlie's orbit, would let it rip inside the church; in a world unknown to white people? Oppression and racism are concepts which I find utterly odious, and I trust all who read these words will share my disdain. However, if we step outside of our personal values, we can begin to understand how the Black church in the American South contributed towards the stabilisation of an inherently unequal society, and to the perpetuation of unequal social norms, and to the safety of its own members. Religious expression existed as a safety valve. It was a way of syphoning off a discontent which would have been too dangerous to express in any other way.

Did Charley Patton represent a similar safety valve? Did his singing represent a secular means of syphoning off bottled up feelings, similar to that offered by the Church? I think he did, and I think that may explain his popularity with White audiences also. He was an exciting performer, and an evening spent dancing to Charley Patton screaming and hollering the blues, must have been one hell of a way of discharging the frustrations of life; as good as getting your sins washed away in the tide.![]() 15

15

To resume the running order; Edward Komara's piece is primarily concerned with illustrating the different social and geographic spheres in which Patton moved. The technique Komara uses is a reversal of A B Lord's principle, that the researcher must begin with the singer and extend outwards, ultimately embracing the whole language area.![]() 16 Such an approach would be impossible in the present case and, taking Mississippi as the 'language area', Komara presents a geographic and diachronic overview of the entire State. From this he narrows the field of vision down, until we can see how the iniquities of history and society moulded Charley Patton, and how they moulded his repertoire. In particular, he discusses the history of Delta agrarianisation, showing how the initial promise of high wages turned sour on the people who poured in there. He also has some interesting observations on the changing nature of Black religion, and shows how Black communities used religion as a protective mechanism against the White supremacist backlash. One wonders how closely this process might be related to the emergence of the sacred-profane dichotomy I discussed earlier. In the changing social climate of the period, to profane the sacred message would not merely have meant damnation in the next world. It would have torn down the protective walls which Black communities built around themselves in this.

16 Such an approach would be impossible in the present case and, taking Mississippi as the 'language area', Komara presents a geographic and diachronic overview of the entire State. From this he narrows the field of vision down, until we can see how the iniquities of history and society moulded Charley Patton, and how they moulded his repertoire. In particular, he discusses the history of Delta agrarianisation, showing how the initial promise of high wages turned sour on the people who poured in there. He also has some interesting observations on the changing nature of Black religion, and shows how Black communities used religion as a protective mechanism against the White supremacist backlash. One wonders how closely this process might be related to the emergence of the sacred-profane dichotomy I discussed earlier. In the changing social climate of the period, to profane the sacred message would not merely have meant damnation in the next world. It would have torn down the protective walls which Black communities built around themselves in this.

I would have liked to have seen Komara's description of Mississippi backed up with a few statistics and his article would have benefited from more extensive referencing. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating piece of writing, and an approach to musical ethnography which I would like to see applied more widely.

On that note we arrive at perhaps the most cogent piece of armoury in Revenant's textual locker. I'm not sure why Dick Spottswood chose to call the transcriptions and song notes Going Away To A World Unknown, unless it was because Patton's records are so difficult to transcribe. Neither do I know why they were published separately from Edward Komara's Thematic Catalogue, which appears as Appendix 1. As it is, notes, texts and original discographical data appear in Spottswood's piece, whilst melodic transcriptions, reissue information, Revenant CD locations, and the sources of the textual transcriptions are in the Komara. To complicate matters, the texts are printed in CD running order, whilst the thematic catalogue is in recording order.

Whatever about that, Patton's texts have been worked over by successive transcribers, each of whom found fresh pieces of the jigsaw with each advance in reproduction technology. The present transcriptions then are not solely the work of Spottswood, but are the culmination of a lot of effort by a lot of people. They are probably about as close as we will ever get to a complete textual register of everything that Charley Patton ever sang - or spoke - on record. Uncertainties and interpolations are shown in brackets and, as far as my English ear could tell, they are pretty spot on. Given the state of the material, and remembering one or two transcriptional disasters I have had to unpick in the past, that is extremely gratifying. I would like to take my hat off to the entire crew.

I was equally gratified to find that most of the tracks were accompanied by extensive and intelligent notes. They are similar to the commentaries which used to be laid out in tabular form on the backs of folk music LPs, but which are seldom entertained by blues record companies. Mercifully, they manage to be erudite and informative without descending to the pedantry, which certain folk LP sleeve note writers used to indulge in.

"That's unsimplifying the simple; which is for me to write it and you to read it." Seamus Heaney

on being asked the meaning of one of his poems.![]() 17

17

It is time to sum up. I began this review by asking two questions. As far as the second is concerned, this package comes about as close as we are ever likely to get in terms of understanding Patton and his artistry. I do not believe that it gives the definitive picture, but I do not believe that a definitive picture is possible or even desirable. That is partly because the events go so far back in time, and there are so many questions which remain unanswered. More particularly, I think it is up to the individual to find their own Charley Patton. For example, I have made much of the theory that Patton was fired by rage, and I have shown that I agree. However, on several occasions, I found this theory treated virtually as though it were established fact. It is not. It is a hypothesis and nothing more, and we cannot know for certain what inspired Patton. Indeed, we would do well to speculate whether any of his style stemmed from singing to large crowds without the aid of a PA.

The articles on Charley Patton's life and times and character contain some valuable clues as to how we should approach his singing. But ultimately it is up to the listener to treat Patton's works as they would any piece of art. That is, to use the imparted information as a key to finding their own interpretation; to look at the facts and interpolations in conjunction with their own emotions and visualise themselves in Charley Patton's place. Only by applying such artistic imagination can the listener discover what it is that moves the listener. By the same token, there is little point in worrying whether Patton saw coherence in his texts. As with any form of poetry, the real issue lies not with the message the creator intended, but with the message the receiver discerns.

"Why don't they cut the prices and let the people eat." Jimmy Witherspoon ![]() 18

18

A phenomenal amount of work has gone into producing this package, and it would be churlish of me to knock it for the price alone. In a world where far too many editors and producers seem to think that near enough is good enough, it is a pleasure to report that this has been beautifully crafted and lovingly assembled. It is true that any statements about production standards need to be qualified in the light of the shortcomings I expressed earlier. In a deluxe package like this, one has a right to expect the producers to get everything right. But at least they succeeded best with the things which matter most. As a single example, turn up the discussion in Appendix 3. There you can read about the extraordinary lengths which were gone to in achieving accurate pitch correction.

Nevertheless, I doubt that adopting such an extravagant format will have done much to help Revenant achieve their stated objective. Had they settled on a more conventional publication - a box containing a book and CD set perhaps - they could still have produced a handsome memoir and got it on the market at a much reduced price. That would have increased sales and would have spread the word of Charley Patton much further.

Nor are my reservations solely concerned with the question of cost. I would willingly accept the format, plus the trimmings, if I felt that they informed my consciousness. I do not think they do. To enjoy and understand Charley Patton, I do not need stick on labels, or reproductions of 78 record sleeves, or imitation 78 records, or blacked up compact discs. And I certainly do not need the whole thing to be boxed up in an artificial album. All these things did was make me feel like a bystander at an Elvis convention: the sort where they seem to think you've got to wear the hair and the sideburns and the jacket and the sneakers before you can appreciate the music. You don't. All you have to do is be a human being with a modicum of intelligence and imagination and feeling and emotion and sensibility; just like Charley Patton.

Fred McCormick - 24.1.02

Unreferenced quotes are taken from the publication under review.

1. From Down the Dirt Road, a BBC Radio 3 Programme about Charley Patton. Transmission date unknown.

2. Paul Oliver, Blues off the Record, 1984, Baton Press, Kent.

3. Revenant do not specify a locale for Walter Hawkins, opining that he must have been an itinerant. However, Paul Oliver's notes to the Saydisc LP suggest that he came from Blythesville, Mississippi County, Arkansas.

4. One side of their disc can be heard on Push Them Clouds Away Musical Traditions MT Cass 101.

5. See The Joe Heaney Interview, this publication.

6. The literature on oral-formulaic creativity is fairly substantial. The best place to start is with A B Lord, The Singer of Tales, 1960, Harvard UP. See also Ruth Finnegan, Oral Poetry, 1977, Cambridge UP, for a succinct appraisal of the arguments surrounding oral-formulaic theory.

7. At any rate, that would accord with John Dollard's findings on the subject. See John Dollard, Class and Caste in a Southern Town, New Haven, Yale UP, 1937. For anyone who may be confused by this, Patton was of mixed African, European and Native American ancestry. He was therefore light skinned and had Caucasian features. As far as the Southern caste system was concerned, Charley Patton was a Negro in a white man's body.

8. Interestingly enough, the H C Speir interview tells us that Speir first came into contact with Patton via a letter which the latter had written him, asking to be recorded. I'm not sure how much this affects my earlier speculation about Patton's choice of record company. However, it may be one more piece of evidence in support of Patton's claims to literacy.

9. The quote comes from a recording of Darling Corey, which I recall hearing Belafonte sing in the late 1950s. The text was a tin pan alley rewrite of the famous Southern Appalachian folksong, with the action shifted to a Black sharecropper's shack and is therefore a rather specious source. Nevertheless, the question is a valid one.

10. Curiously enough, while I was mulling over this, I heard the radio psychiatrist, Dr Anthony Clare, speculating on high rates of heart disease among Southern Black males. Clare felt that the phenomenon was at least partly attributable to the need to suppress anger in the face of white supremacism. I do not know whether Clare's thoughts can be backed up by hard facts. However, allowing for other potential factors such as poor diet and high alcohol intake, it sounds a reasonable hypothesis. I should point out that Patton's own heart trouble was linked to a rheumatic condition.

11. At any rate, I presume Evans is applying the word conscience in its normal usage; to imply that Patton was a sort of moral guardian. I am though conscious that he may be using the term in its less familiar sense, to denote the totality of a people's thoughts and feelings. If so, Evans may be suggesting that Patton represented a channelling of the emotions of Black Delta people at large; shared experience given vent to in song. If that is the case, I am much more inclined to agree.

12. I Got the Blues, Blue Note BLN LA 5332h2, Classics of Modern Blues.

13. Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, London, George Allen and Unwin, 1982.

14. Dollard. Ibid

15. I am of course aware that white Southerners were themselves no strangers to flamboyant demonstrations of religious zeal. Moreover, I feel that White religion was no less emotionally cathartic than its Black equivalent. However, if we wish to understand the function of religious catharsis among Whites, we have to accept that it must have arisen from a different socio-cultural motivation. Without wishing to air hypotheses irrelevant to the present work, I wonder if the need for White religious catharsis stemmed less from pent up anger, than from the emotional uncertainty of living in a culture of conflicting social values. IE., although White Southerners placed great emphasis on salvation through pious behaviour and good living, their world was more often typified by hell-raising and violence.

16. Quoted in Where I come from they all sing like that; booklet article by Liam Mac Con Iomaire, accompanying the CD release, Joe Heaney: The Road From Connemara, Topic TSCD 518D.

17. From a BBC TV schools programme on the meaning of poetry. Date and title unrecalled.

18. Times Gettin' Tougher than Tough. Vogue JL 91: Olympia Concert, Paris 1961.

Charley Patton

1. Pony Blues

2. A Spoonful Blues

3. Down The Dirt Road Blues

4. Prayer Of Death - Part 1

5. Prayer Of Death - Part 2

6. Screamin' And Hollerin' The Blues

7. Banty Rooster Blues

8. Tom Rushen Blues

9. It Won't Be Long

10. Shake It And Break It (But Don't Let It Fall Mama)

11. Pea Vine Blues

12. Mississippi Boweavil Blues

13. Lord I'm Discouraged

14. I'm Goin' Home

[10 second gap]

Walter "Buddy Boy" Hawkins

15. Snatch It And Grab It

16. A Rag Blues

17. How Come Mama Blues

18. Voice Throwin' Blues

Charley Patton

-2. Hammer Blues (take 1; uniss.)

1. I Shall Not Be Moved (take 1; uniss.)

1. High Water Everywhere - Part I

2. High Water Everywhere - Part II

3. I Shall Not Be Moved

4. Rattlesnake Blues

5. Going To Move To Alabama

6. Hammer Blues (take 2)

7. Joe Kirby

8. Frankie And Albert

9. Devil Sent The Rain Blues

10. Magnolia Blues

11. Running Wild Blues

12. Some Happy Day

13. Mean Black Moan

14. Green River Blues

[10 second gap]

Edith North Johnson

15. That's My Man

16. Honey Dripper Blues No. 2

17. Eight Hour Woman

18. Nickel's Worth Of Liver Blues No. 2

Charley Patton

-2. Some These Days I'll Be Gone (take 1; uniss.)

-1. Elder Greene Blues (take 2; uniss.)

1. Jim Lee-Part I

2. Jim Lee-Part II

3. Mean Black Cat Blues

4. Jesus Is A Dying-Bed Maker

5. Elder Greene Blues (take 1)

6. When Your Way Gets Dark

7. Some These Days I'll Be Gone (take 2)

8. Heart Like Railroad Steel

9. Circle Round The Moon

10. You're Gonna Need Somebody When You Die

[10 second gap]

Henry "Son" Sims

11. Be True Be True Blues

12. Farrell Blues

13. Tell Me Man Blues

14. Come Back Corrina

Charley Patton

1. Some Summer Day

2. Bird Nest Bound

[10 second gap]

Willie Brown

3. Future Blues

4. M&O Blues

[10 second gap]

Son House

5. Walkin' Blues (uniss.)

6. My Black Mama-Part I

7. My Black Mama-Part II

8. Preachin' The Blues-Part I

9. Preachin' The Blues-Part II

10. Dry Spell Blues Part I

11. Dry Spell Blues Part II

[10 second gap]

Louise Johnson

12. All Night Long Blues (take 1)

13. On The Wall

14. All Night Long Blues (take 2; uniss)

15. By The Moon And Stars

16. Long Ways From Home

Disc 5: May/June 1930, January-February 1934

June 1930

Charley Patton

1. Dry Well Blues

2. Moon Going Down

[10 second gap]

May 1930

Delta Big Four

3. We All Gonna Face The Rising Sun

4. Moaner Let's Go Down In The Valley

5. Jesus Got His Arms Around Me

6. God Won't Forsake His Own

7. I'll Be Here

8. Where Was Eve Sleeping?

9. I Know My Time Ain't Long

10. Watch And Pray

[10 second gap]

HC Speir

11. Paramount Test 1-4/19/30 headlines

12. Paramount Test 2-4/12/30 headlines

[10 second gap]

January-February 1934

Charley ("Charlie") Patton

13. High Sheriff Blues

14. Stone Pony Blues

15. Jersey Bull Blues

16. Hang It On The Wall

17. 34 Blues

18. Love My Stuff

19. Poor Me

20. Revenue Man Blues

[10 second gap]

Patton and Lee

21. Troubled 'Bout My Mother

22. Oh Death

[10 second gap]

Bertha Lee

23. Yellow Bee

24. Mind Reader Blues

Disc 6: Charley's Orbit - Songs

1. Ma Rainey - Booze And Blues (1924) 3:08

2. Walter Rhodes - The Crowing Rooster (1927) 3:22

3. Furry Lewis - I Will Turn Your Money Green (1928) 3:11

4. Rube Lacy - Ham Hound Crave (1928) 2:53

5. Tommy Johnson - Bye Bye Blues (1928) 3:11

6. Tommy Johnson - Maggie Campbell (1928) 3:39

7. Tommy Johnson - Big Road Blues (1928) 3:23

8. William Harris - Kansas City Blues (1928) 3:01

9. Kid Bailey - Rowdy Blues (1929) 3:01

10. Kid Bailey - Mississippi Bottom Blues (1929) 3:01

11. Blind Joe Reynolds - Cold Woman Blues (1929) 2:59

12. Mississippi Sheiks - Sitting On Top Of The World (1930) 3:01

13. Charley Jordan - Just A Spoonful (1930) 2:41

14. Blind Pete And George Ryan - Banty Rooster (1934) 2:14

15. Big Joe Williams - My Grey Pony (1935) 3:08

16. Willie Lofton Trio - Dark Road Blues (1935) 3:02

17. Unknown Convict - Blues (1936) 2:47

18. Bukka White - Sic 'Em Dogs On (1939) 2:21

19. Bukka White - Po' Boy (1939) 2:50

20. Willie Brown - Make Me A Pallet On The Floor (1941) 3:29

21. Son House - County Farm Blues (1942) 2:22

22. The Howlin' Wolf - Saddle My Pony (1952) 2:34

23. The Howlin' Wolf - Forty Four (1954) 2:47

24. Roebuck "Pops" Staples & Staple Singers - Too Close (1957) 5:23

Disc 7: Charley's Orbit - Interviews

1. The Howlin' Wolf, interviewed by Pete Welding, ca. 1967

2-16. Booker Miller, interviewed by Gayle Dean Wardlow, 1968

17-25. HC Speir, interviewed by Gayle Dean Wardlow, 1968, 1969

26. Roebuck "Pops" Staples, interviewed by Chris Strachwitz, ca.

| Top of page | Home Page | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |