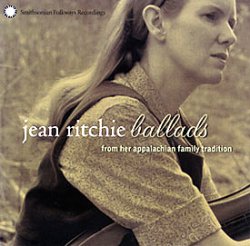

ballads from her appalachian family tradition

Smithsonian Folkways SFW CD 40145

1. Gypsy Laddie; 2. False Sir John; 3. Hangman; 4. Lord Bateman; 5. The House Carpenter; 6. Lord Thomas and Fair Ellender; 7. The Merry Golden Tree; 8. Old Bangum; 9. Barbary Allen; 10. The Unquiet Grave; 11. Sweet William and Lady Margaret; 12. There Lived an Old Lord; 13. Cherry Tree Carol; 14. Edward; 15. Lord Randall; 16. Little Musgrave. Duration 73 mins.Issued, originally, on two Folkways LPs, Jean Ritchie - ballads from her appalachian family tradition is a stunning collection of sixteen Child ballads sung by one of the most outstanding singers ever to emerge from the Appalachian singing tradition.

Three of the ballads - Old Bangum (Child 18), Sweet William and Lady Margaret (Child 74) and Hangman (Child 95) - have dulcimer accompaniment, the rest are sung unaccompanied.

Three of the ballads - Old Bangum (Child 18), Sweet William and Lady Margaret (Child 74) and Hangman (Child 95) - have dulcimer accompaniment, the rest are sung unaccompanied.

Many years ago, Peter Kennedy told me that when he was looking for singers in a new area he would try to seek out the most intelligent people that he could find. "They tended to know the best songs. You didn't look for the village idiot", he said. These words came back to me as I began to read the booklet notes to this CD. The Ritchie Family, far from being simple backwoods folk, were clearly some of the brightest people in their part of the mountains. Jean's main source for the ballads were her father, Balis W Ritchie (b.1869), her mother, Abigail Hall Ritchie (b.1877) and 'Uncle' Jason Ritchie, who was actually one of Balis Ritchie's first cousins. According to Jean, Jason was 'fairly well educated and practiced law for several years. Both he and Balis were deeply interested in education.' At one time Balis travelled to Ohio to attend school there, returning home to teach for ten years. 'He had the first printing press in those parts, which was ordered by mail and brought the last forty miles to his home with mules and wagon. In time he put together a little songbook, about twenty pages, and for its spine he laid the ten sheets of paper in a stack, flat, and sewed down the middle with a sewing machine, using the large-stitch setting. The content was mostly old family songs like Jackaro, I've Been a Foreign Lander, and Lord Thomas and Fair Ellender. But he was very proud to include some modern ones, learned from the occasional traveler through the hills who would stop and stay the night ... Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home and Kitty Wells are in his book alongside the old ones.'

In his introductory remarks to the CD, Kenny Goldstein makes this important observation. 'As a result of my own folksong collecting in the Southern mountains, New England and Scotland, I have come to the conclusion (which is undoubtedly shared by other collectors as well) that a vital folksong tradition is dependent upon more than a great amorphous mass of 'ordinary' folksingers. To be sure, they are an essential part of the picture. But far more important are those few highly gifted tradition bearers whom the 'ordinary' folk themselves recognize as the best or great singers of their respective communities.' And, of course, Jean Ritchie falls well within this definition, alongside such singers as Jeannie Robertson, Harry Cox, Walter Pardon and the Stewarts of Blair. Goldstein continues, 'These are the folk with the largest repertoires, the finest voices (in terms of a folk aesthetic), the most representative and engaging singing styles, and who are the greatest creative and re-creative singing personalities. These are the folk who are the major inspirational force in a singing community - it is their songs, their versions, and their style which are borrowed, copied, or imitated by their friends, neighbours, and relatives. If folksong tradition is vanishing, it is mainly because there are far fewer of these 'great' singers alive today than there were in past decades and centuries.'

It comes as no surprise to read that Jean Ritchie was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship Award from the National Endowment for the Arts, 'in recognition of her significant contribution to folk and traditional arts'. What is a surprise is the fact that she was only given the Award as late as 2002. When we remember that her first book, Singing Family of the Cumberlands, was published almost fifty years ago, that she has recorded several dozen albums, that she has almost single-handedly revived interest in the Appalachian Dulcimer, and that she has performed in thousands of concerts - then the Award does seem rather tardy.

So, what of this CD? The opening track Gypsy Laddie (Child 200) begins with the verse:

An English Lord came home one night,which puts us well and truly in the Old World, and I do sometimes wonder if some of the Appalachian singers have retained such ballads as a way of reinforcing their feelings about their ancestral homelands. Some of Jean's ballads show clear connections with British versions. Take, for example, her version of Little Musgrave (Child 81), which contains the placename 'Bucklesfordberry'. This is a place mentioned in both Child's A and B versions, the first dated to an English drollery of 1658, the second from the Percy mss, and this suggests that the ballad has been in oral tradition for at least 300 years. And what of Lord Thomas and Fair Ellender? Again, there are mid-17th century English broadsides, but, what really interests me is the fact that Jean's tune is actually a version of the well-known Dives and Lazarus family of tunes. Broadsides texts seldom included printed tunes. So, again, we are presented here with a tune that almost certainly came from the Old World.

Inquiring for his lady.

The servants said on every hand,

"She's gone with a gypsy laddie."

One ballad, the beautiful Edward (Child 13), is of great interest to me, but for different reasons. According to Kenny Goldstein, 'Jean Ritchie's version, learned from her sisters Patty, Edna, Una, and May (who first learned it at the Hindman Settlement School), is similar to most versions collected in the Southern Appalachians'. Elsewhere Jean writes that the Hindman songs were, 'known to everybody in that community ... the Settlement school's songbooks were made up of songs brought in by the children from their families' repertoires. Thus, the titles credited as having been learned at the school were versions of ones our family already knew, at least in part if not the whole song'. In other words, Jean is claiming that songs learnt at school were, in effect, locally-know songs that were being 'recycled' back into the community. But, in the case of her version of Edward there is another possibility. On 20th September, 1917, English song collector Cecil Sharp paid a visit to the Hindman Settlement School. Whilst there he collected a version of the song Nottamun Town from Jean's sister Una. Sharp and his assistant Maud Karpeles had previously visited another Kentucky mountain school at Pine Mountain and an account of this visit is given by Evelyn Wells. 'There was an hour after supper in our big dining room, where after the day of farm work and canning and other vacation occupations, we settled back in our chairs while those two (i.e. Sharp & Karpeles) sang to us - The Knight and the Child in the Road, All Alone in the Ludeney, Edward, The Gypsy Laddie'. Jean Ritchie's version of Edward is uncommonly close - both words and tune - to the set that Sharp had collected on 15th April, 1917, from Trotter Gann, of Sevierville, Tennessee; and I would suggest (although I cannot prove this suggestion) that Sharp sang Mr Gann's version of Edward both at Pine Mountain and, later, at Hindman; and that it was from Sharp's singing, directly or indirectly, that the ballad Edward passed to the Ritchie sisters.

One other ballad was learnt from outside the family. Sweet William and Lady Margaret (Child 74), sung to the tune of Willie Moore, came from the singing of Justis Begley of Hazard, Kentucky. Well-known locally for his banjo playing and singing, Begley can be heard singing a version of The Merry Golden Tree (Child 286) on one of the seven CDs that comprise the collection Kentucky Mountain Music (Yazoo 2200). Jean's own version of this ballad came from her mother. Incidentally, the Yazoo set also includes another Kentucky version of Sweet William and Lady Margaret, this time one recorded by Alan Lomax from the singer Daw Henson of Clay County. Try, if you can, to hear Henson's version as it differs somewhat from the Ritchie Family set.

The Unquiet Grave (Child 78) is something of an Appalachian rarity. Once relatively well-known in Britain, it has seldom surfaced in America. It came from Uncle Jason, as did the splendid versions of False Sir John (Child 4) and The Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54). Uncle Jason also gave Jean her version of Lord Randall (Child 12), which is carried on a tune similar to that used for the song Bachelor's Hall which Jean sings elsewhere.

Jean Ritchie - ballads from her appalachian family tradition is an essential CD, for both scholars and singers alike. It contains a marvellous selection of ballads some rare, others, such as Lord Bateman (Child 53), The House Carpenter (Child 243) or Old Bangum (Child 18), not so rare, sung by one of the most talented folksingers that we have. I love the album and am grateful that it has, at last, been reissued on CD.

Mike Yates - 9.8.03

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |