| Keola Beamer

|

| Kolonahe - from the gentle wind

|

|---|

| Dancing Cat Records 38047

|

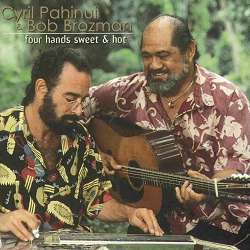

| Cyril Pahinui & Bob Brozman

|

| Four Hands Sweet & Hot

|

|---|

| Dancing Cat Records 38048

|

| Led Kaapana & Friends

|

| Waltz of the Wind

|

|---|

| Dancing Cat Records 38016

|

The greatest, most persistent problem with Hawaiian music is the very thing that accounts for its recurrent popularity. The superficial appeal of the exotic was no doubt responsible for the Hawaiian 'craze' which so informed the development of twentieth-century popular music. The music's decline by the time of the second World War was the inevitable consequence of what the record industry calls 'over-exposure'. Its revival after the war may have been due to a new awareness of the Pacific region in general; but there was nothing new in the idea that music from warm islands is the proper accompaniment to a mildly erotic, chemically enhanced, open-air reverie. A valiant effort was made to save reggae from the same fate, by claiming it as a sacred protest music; but, for the average consumer, it remains the music of choice for the drowsy section of long-haul pop festivals – which is fair enough, I suppose, since most of its practitioners seem to spend their entire lives in a chemically enhanced reverie.

I recently read a record review in a Sunday newspaper, which referred in passing to 'Hawaiian loungecore'. I confess that I hadn't encountered the term before, and can't be sure that I've ever experienced the phenomenon it denotes; but I fear I know exactly what it means. The one thing it is hardly likely to refer to is any form or development of music. Like 'easy listening', which some people imagine to be a musical genre, it is presumably a marketing category for people who don't like music.

Those of us who would rehabilitate Hawaiian music, or at least acknowledge its potency and historical importance, may be dismayed to find that Dancing Cat, the company responsible for these three CDs, is apparently part of the Windham Hill group. Windham Hill is known, rightly or wrongly (and I claim no intimacy with its catalogue) as a 'new age' label, specializing in 'ambient sound' – or background noise, as you or I might call it. This is an ominous association, for those who are not (necessarily) seeking a ready-made atmosphere for poolside barbecues.

Keola Beamer's album, Kolonahe – from the gentle wind (the subtitle seems to be a translation), confirms my fears. Beamer is described as 'one of the most innovative and influential slack key guitarists of the modern era', and I don't doubt it.  He's a highly accomplished musician, and represents 'one of Hawaii's best known musical clans'. In 1973, at only twenty-two years old, he released his first solo album, Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar in the Real Old Style, and published the first slack key instruction book. His music will no doubt work very well as background. It surely doesn't deserve that; but, like many of his fellows, Beamer seems to collude in the romantic colonial stereotyping which has always coloured the common perception of Pacific cultures, and which is at least as prominent a feature of the recent Hawaiian renaissance as it was of any previous period of the music's popularity.

He's a highly accomplished musician, and represents 'one of Hawaii's best known musical clans'. In 1973, at only twenty-two years old, he released his first solo album, Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar in the Real Old Style, and published the first slack key instruction book. His music will no doubt work very well as background. It surely doesn't deserve that; but, like many of his fellows, Beamer seems to collude in the romantic colonial stereotyping which has always coloured the common perception of Pacific cultures, and which is at least as prominent a feature of the recent Hawaiian renaissance as it was of any previous period of the music's popularity.

The notes to this album are credited to Jay W Junker and George Winston. Winston is the producer of Dancing Cat's slack key series, and contributes some good piano and occasional guitar parts. In reading of Keola Beamer's impressive credentials, we're told that 'Hawaiian society has always placed a high value on sound'. What exactly does that mean? Well, if you believe that music is about sound, it provides a handy introduction to any discussion of Hawaiian musicality. Indeed, it appears to serve as an explanation of Hawaiian musicality.

'In Hawaii,' the notes continue, 'the creative impulse usually stems from a pleasurable experience'. In the case of this album, 'the concept for Kolonahe came to Keola one afternoon in Maui', in the form of 'the most beautiful, refreshing breeze'. Music, it seems, is not a cerebral activity, but takes place in the ears, or perhaps even on the skin. The wonder and mystery do not end there. Beamer is rightly celebrated for combining 'elements of the ancient and the modern, the indigenous and the introduced'. As well as leading in such innovations as multi-track recording and electronic effects, he incorporates passages of traditional chant, and plays pre-colonial instruments, namely the bamboo nose flute and lava stone castanets. He has an apparently unique method of playing the latter simultaneously with the guitar, using the first three fingers of his right hand, while sounding the guitar with only the fourth finger; which is, let's face it, very clever, and it added something to my listening to know that. I was less impressed by the assertion that 'playing 'ili 'ili' (i.e. clicking two pebbles together) 'is as much an act of reverence as an artistic expression'. Because, you see, stones are very old. As for the nose flute, Beamer says, 'That beautiful, ethereal sound is like wind off in the distance'. Oh good, here comes that wind again. The notes continue, 'Because it's played with breath from the nostrils, the 'ohe hano ihu forms a very close communion with the few who play it'. Americans, I believe, usually refer to flatulence as 'gas' rather than 'wind', so they are untroubled by the less ethereal association which Kolonahe will always have for me, thanks to these notes.

In keeping with 'the concept', the music on this album maintains a slow to moderate pace throughout. Beamer's Hawaii knows only gentle breezes. The playing is lovely; any guitarist would probably gain something from it. The singing is pretty good, too. The songs are mostly more or less old, and more or less typical – as far as I can tell, since they are in Hawaiian. There are, however, two of Beamer's own songs, in English, and they pretty well fit the general pattern, being lonesome, nostalgic paeans to his homeland. The Beauty of Mauna Kea begins with a chanted poem by Nona Beamer, Keola's mother, introducing a simple, quietly affecting song about how the cloud-wreathed peak which was the backdrop to his youth haunts his dreams, since he moved to the city. Honolulu City Lights is about flying from the city at night. I may have heard it before, but I fear that its familiarity is because it's that song we've all heard before – the one written by ninety-nine-point-nine percent of all singer-songwriters.

Which raises the question why Hawaiian songs do seem to be so unvaried. Why are they usually about mountains, flowers and balmy weather? The association of such things with instrumental pieces is an essentially meaningless but unobjectionable convention; they have to be called something, and names are better than numbers. Many of the popular instrumentals, however, are the tunes associated with songs, which generally turn out to be the same old thing, in terms of content. Many of the old songs are proudly declared to be products of the 'monarchy era', written for, and often by, Hawaiian royalty. Their tone and content, therefore, are unsurprising; courtly cultures are inherently conservative, and unlikely to produce anything controversial. But was that the only Hawaiian culture, even then?

Generally speaking, I have no sympathy with the vulgar notion that traditional songs are justified by 'contemporary relevance', but I can't help wondering where the songs are, that reflect the everyday lives of ordinary Hawaiians. The range of moods expressed by modern performers, at least as exemplified by Keola Beamer, is unnaturally narrow. It may be, for instance, that much of the humour which characterizes the commercial recordings of the 1920s & '30s is due to the interaction with Tin Pan Alley and vaudeville; but I know that Hawaiians do not lack humour, and some confirmation of that would be, to return to Beamer's theme, a breath of fresh air. If the traditional repertory really is so one-dimensional, what of today's songwriters? 'Hawaii is a lovely place' can't be all they have to say. Common sense dictates that Hawaiians are not the simple, happy-go-lucky sons of the soil that we are (still) invited to see them as. Has no-one ever written a song expressing the experience of an annexed state of the Union? Perhaps there are such songs, but they are performed by Hawaiian indie rockers. In which case, I'll make do with mountains, flowers and balmy weather.

Four Hands Sweet & Hot is in the same modern slack key series, but is also in a sub-series of albums presenting slack key & steel guitar duets, played in this case by Cyril Pahinui & Bob Brozman. Cyril Pahinui is a son of the late, great Gabby Pahinui,  the most famous of all modern Hawaiian musicians, who is credited with having made the first slack key recording, in 1946, and was largely responsible for establishing 'slack key' as a distinct genre. Cyril was a sweet-faced twenty-four-year-old with plenty of head hair, when he played on The Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band Vol. 1 (the one with Ry Cooder), in 1974. Much of the hair had migrated southwards, by the time he and his two brothers released their own album (the one with Ry Cooder) in 1992. His own award-wining solo debut on Dancing Cat was released two years later.

the most famous of all modern Hawaiian musicians, who is credited with having made the first slack key recording, in 1946, and was largely responsible for establishing 'slack key' as a distinct genre. Cyril was a sweet-faced twenty-four-year-old with plenty of head hair, when he played on The Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band Vol. 1 (the one with Ry Cooder), in 1974. Much of the hair had migrated southwards, by the time he and his two brothers released their own album (the one with Ry Cooder) in 1992. His own award-wining solo debut on Dancing Cat was released two years later.

The steel guitar, it has to be said, is something of a Frankenstein's monster. The sound which, for most people, is the identifying characteristic of Hawaiian music – having been adapted to blues and country music, and their various subdivisions – has in the past twenty years become tiresomely ubiquitous. There seems to be a law that incidental music in films and television programmes must be provided by a guitar played with a slide, especially where the great outdoors is concerned, and even if the great outdoors in question is, say, Wiltshire.

Perhaps that is why serious musicians in Hawaii appear largely to have abandoned the technique. All the slack key players could play steel guitar, if they chose to, and probably do so as required. The crucial defining feature of Hawaiian guitar, after all, is the proliferation of tunings: you can fingerpick your unconventionally-tuned guitar in a gently percussive manner, with lots of hammering on, pulling off, and sounding of harmonics; or you can raise the nut and stop the strings with a smooth object. Today's Hawaiian masters, however, proclaim 'slack key' to be the true national form, and evidently regard steel playing as a relic of a bygone era, best left to enthusiasts from the mainland. Cyril Pahinui played steel guitar on one track of the Pahinui Brothers album; the rest was taken care of by Ry Cooder and David Lindley.

Such enthusiastic outsiders are likely to have come to the music via mainland forms, and to have been inspired by the Hawaiian influence on the jazz/swing age. Bob Brozman is the most singleminded of them. For some years, now, he has been a tireless champion of, and collaborator with, Hawaiian musicians, and has established himself as probably the world's leading exponent of old-fashioned Hawaiian steel guitar. He also played, once upon a time, with The Cheap Suit Serenaders, which says everything about his preferences (and means that he can get away with a great deal, as far as I'm concerned). Brozman is credited with both co-production of this album, and co-authorship of the notes, which are mostly about the music, and mercifully free of the embarrassing drivel mentioned above.

It hardly needs stating that the music, too, is much more to my taste. While Keola Beamer's primary mainland influence seems to be that branch of American pop music catering for people with dangerous heart conditions (they call it 'folk', I gather), this music has, as the album's title indicates, heat as well as sweetness, humour and excitement as well as poignancy and downright sentimentality. Cyril Pahinui's style is rooted in his father's era, the 1940s & '50s, and is informed by swing and by Latin American music. According to Brozman, Cyril's most distinctive characteristic is his constantly syncopated Latin-American thumb action. Brozman's own approach, of course, is pre-WWII, and most heavily influenced by Sol Hoopii and Tau Moe. He doesn't know the restraint for which Ry Cooder is justly celebrated; like most such enthusiasts, Brozman will generally go that one step further than is strictly necessary; but he plays like a demon, and I'm glad he's there, to preserve the role of steel guitar in Hawaiian music.

Apart from a shared composition in honour of their friend Led Kaapana, and a tune written in the 1970s by Eddie Kamae, the material is all quite elderly, and mostly familiar. Cyril Pahinui sings two songs, both previously recorded by his father: E Nihi Ka Hele, which appears on The Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band Vol. 1, and Hula O Makee. Strangely, the box and booklet both indicate that he also sings Inikiniki Malie, which was recorded in 1927 by Kalama's Quartet. In fact, this is an instrumental workout, which alludes to the melody rather than stating it in full, suggesting that it might indeed have been intended as an accompaniment. Was the vocal track abandoned at some point, or simply mislaid?

Incidentally, I was not previously aware that Brozman's historic collaboration with the Moe family (the Rounder album Remembering the Songs of Our Youth , released in 1989) had led to a documentary film by fellow Cheap Suit Terry Zwigoff. This is both exciting and distressing news: the film is shot but unfinished for want of funding.

Bob Brozman turns up again, on Waltz of the Wind; or, rather, had turned up already, as this album was in fact released in 1998. Brozman has been collaborating with Ledward Kaapana for some years, and they released an album of duets in 1995. On this album, he contributes his trademark steel to Kaapana's own song My Sweetheart, and a straight rhythm accompaniment to the jazzy Hanohano Hanalei, which Kaapana plays on tenor guitar. Brozman's presence is not the only reason that these two tracks are the most like the material on the albums already discussed.

This album makes no claim to Hawaiian purity. It is an 'all-star' collaboration – what might once have been called a 'fusion' project. Recorded mainly in Nashville, it combines one of Hawaii's most popular and versatile musicians with some of the 'rootsier' stars of the current country scene. According to the box, 'This is the first recording combining players from Hawaiian, Country and Bluegrass music, three uniquely American traditions'. This claim relies, of course, on the specific inclusion of bluegrass; it isn't hard to find examples of such collaboration, before that term was adopted. This supposedly new combination (which depends for its novelty on the proposition that country & bluegrass are necessarily distinct forms) seems to me to have its own peculiar interest. I've commented before on the status of bluegrass; that it is widely regarded as the purest, most essential of Anglo-American musical traditions, in spite of its relatively short history and its emphasis on innovation. The first solo recordings of slack key guitar were made around the same time as the first 'official' bluegrass records; 'slack key' is now regarded as a distinct genre, as the true heart of Hawaiian musical tradition, and as the locus of all significant modern development.

Whatever tradition Waltz of the Wind may be considered to represent, it contains some highly enjoyable music. The title track features the voice and viola of Alison Krauss. Kaapana plays ukulele, as he does on three others: an instrumental version of Bert Kaempfert's Spanish Eyes, the western swing standard Steel Guitar Rag, on which Jerry Douglas provides the steel guitar, and Hank Williams' Move It On Over, which is sung by Ricky Skaggs, and features his mandolin as well as Douglas's Dobro. Kaapana's ukulele playing is splendid, and to hear him swapping solos with Skaggs is fascinating. He also fingerpicks autoharp, on an instrumental performance of Koke 'e, with Stuart Duncan on fiddle, and Kaapana's own overdubbed guitar. My first reaction on hearing his autoharp playing was that it was surprising that there was no Hawaiian autoharp tradition. Well, according to Led Kaapana, there is such a tradition – in his home village of Kalapana, at least.

Apart from Marian Santiago's sludgey 'ballad' Yesterday, everything on this album is worth listening to. Perhaps the most surprising, and immediately enjoyable, item is an exhilarating romp through the well-known cajun two-step Les Flammes d'Enfer, with Sonny Landreth on electric slide guitar. All in all, I think this venture is a success, and look forward to the next. I shall also take an interest in other releases on the Dancing Cat label, which has overcome my initial suspicion. I'd like to think they might avoid the touchy-feely, sacred simpleton approach, in future, but I fear that's too much to hope. If they suppose that approach to have the broadest commercial appeal, they're probably right.

David Campbell - 13.3.00

Site designed and maintained by Updated: 21.11.02

He's a highly accomplished musician, and represents 'one of Hawaii's best known musical clans'. In 1973, at only twenty-two years old, he released his first solo album, Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar in the Real Old Style, and published the first slack key instruction book. His music will no doubt work very well as background. It surely doesn't deserve that; but, like many of his fellows, Beamer seems to collude in the romantic colonial stereotyping which has always coloured the common perception of Pacific cultures, and which is at least as prominent a feature of the recent Hawaiian renaissance as it was of any previous period of the music's popularity.

He's a highly accomplished musician, and represents 'one of Hawaii's best known musical clans'. In 1973, at only twenty-two years old, he released his first solo album, Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar in the Real Old Style, and published the first slack key instruction book. His music will no doubt work very well as background. It surely doesn't deserve that; but, like many of his fellows, Beamer seems to collude in the romantic colonial stereotyping which has always coloured the common perception of Pacific cultures, and which is at least as prominent a feature of the recent Hawaiian renaissance as it was of any previous period of the music's popularity.

the most famous of all modern Hawaiian musicians, who is credited with having made the first slack key recording, in 1946, and was largely responsible for establishing 'slack key' as a distinct genre. Cyril was a sweet-faced twenty-four-year-old with plenty of head hair, when he played on The Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band Vol. 1 (the one with Ry Cooder), in 1974. Much of the hair had migrated southwards, by the time he and his two brothers released their own album (the one with Ry Cooder) in 1992. His own award-wining solo debut on Dancing Cat was released two years later.

the most famous of all modern Hawaiian musicians, who is credited with having made the first slack key recording, in 1946, and was largely responsible for establishing 'slack key' as a distinct genre. Cyril was a sweet-faced twenty-four-year-old with plenty of head hair, when he played on The Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band Vol. 1 (the one with Ry Cooder), in 1974. Much of the hair had migrated southwards, by the time he and his two brothers released their own album (the one with Ry Cooder) in 1992. His own award-wining solo debut on Dancing Cat was released two years later.