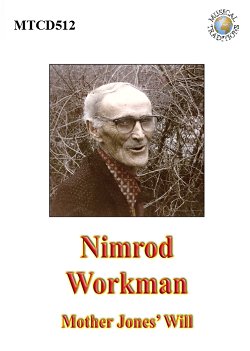

Mother Jones' Will

Musical Traditions MTCD512

Lord Baseman. My Pretty Little Pink. The City Four Square. Sweet Rosie. Lord Daniel. Remember What You Told Me, Love. Rock the Cradle and Cry. Coal Black Mining Blues. Mother Jones' Will. The Drunkard's Lone Child. What is that Blood on Your Shirt Sleeve? Working On This Old Railroad. Black Lung Song. I Want to Go Where Things are Beautiful. Biler and the Boar. The Devil and the Farmer. Loving Henry. Darling Cory. The Stone that was Hewed Out of the Mountain. Little David Play on Your Harp (with Molly Workman). Brother Preacher. In the Pines. Newsy Woman. Oh, Death. The Carolina Lady. Little Bessie (with Molly Workman).

In 1918 Cecil Sharp spent less than a week in West Virginia, a place that was not to his liking.

In 1918 Cecil Sharp spent less than a week in West Virginia, a place that was not to his liking.

Nimrod Workman was born in Martin County, Kentucky, in 1895 and died in Knoxville, Tennessee, aged 99 years, in 1994, although he spent most of his life, as a miner, in Chattaroy, West Virginia. He was only 14 years old when he started work in the Howard Collieries coal mines in Mingo County, WV, where he quickly became active in union politics. In the early 1920s he worked alongside the activist Mary Harris 'Mother' Jones and in 1921 took part in a massive strike, later known as the Battle of Blair Mountain, where some 10,000 - 15,000 miners took on the Logan County, West Virginia, coal bosses; the latter being backed by the police and, later, the US Army. It is estimated that some one million rounds were fired at the miners during this attempt to establish unions. No wonder Nimrod Workman turned out to be the man that he was! In later years he worked to bring compensation to the miners who, like himself, had contracted black lung disease. And during all this time, he sang. Not only the old ballads that his parents had sung to him as a child, but also his own compositions, such as Mother Jones' Will, Coal Black Mining Blues and his poignant Black Lung Song.

Mother Jones' Will contains a selection of twenty-six songs from Nimrod's large repertoire. There are nine old-world songs and ballads (including six Child ballads), a few North American songs, some religious and/or sentimental/didactic pieces, and, of course, the three songs mentioned above, that were written by Nimrod himself. He was a consummate artist, one who really had to be seen to be believed. As fellow singer David Holt once said, "As a singer and performer you couldn't take your eyes off him. Angular, spidery and animated he sang the old ballads as well as the songs he wrote in a rough hewn voice that was clearly from another time."

Many of Nimrod Workman's ballads clearly were from 'another time'. Take the short version of Biler and the Boar, for example, which opens with this stunning verse:

Perhaps the same thing happened, to some extent, in the Appalachian Mountains of America, where communities were often isolated and where traditions were more reliant on oral transmission. When Cecil Sharp met the Mitchell family of singers in Burnsville, NC, he noted that, 'They are considered a very low-down lot by the richer people here who wonder why we like them and go there so often.' In 1980 I had the same experience when I met people in the town of Asheville, NC, who could not understand why I was 'wasting my time' visiting singers in the area around Sodom Laurel. "They were", they said, "just hillbillies". Of course, many mountaineers were literate and books, such as Bradley Kincaid's 1928 songbook, did circulate throughout Appalachia. But this was a later development and I feel certain that many of the singers who sang to Cecil Sharp during the period 1916 - 18 were singing songs and ballads that had survived for several generations without reliance on print.

As a slight footnote to the question of literacy, I recalled the singer Dan Tate once starting a sentence with the words, "Well, Mike, as Socrates once said…" And on another occasion he quoted a couple of lines from one of Shakespeare's plays. I may query what Mark says on this subject, but he does have a valid point and I'm sure that scholars will be mulling this one over for years to come.

Another ballad, Lord Baseman, which opens the album, is yet another gem, and is set to a version of the tune that many Appalachian singers, including Nimrod Workman, use for the song The Carolina Lady. Mark Wilson notes that the ballad was 'commonly printed in early American songsters', suggesting, I suppose, that these texts could have entered American tradition, although he rather contradicts himself by adding that the name 'Suslan Pine', as used by Nimrod Workman, is 'of considerable antiquity'. Perhaps, on some occasions, the printed texts did play a part in the Appalachian song tradition. But, if this was the case, then these texts were, I suggest, being added to an already existing oral tradition.

Loving Henry, on the other hand, is rather let down by its tune, namely the one that Appalachian singers almost always use for the ballad of The House Carpenter. (You can hear Nimrod singing The House Carpenter, along with a few other songs and ballads, on the Musical Traditions four-CD set Meeting's a Pleasure. Folksongs of the Upper South MTCD505-6 and MT507-8). As for the other 'British' songs, I especially like the short, fragmentary, Remember What You Told Me, a song that still turns up in England today as The Lily-White Hand (Roud 564), and Rock the Cradle and Cry, a song that can be traced back to 17th century English broadsides, although, for some reason or other, I always seem to feel that there is an Irish connection somewhere in there!

My Pretty Little Pink, In the Pines and Working On This Old Railroad are good, if short, examples of Appalachian songs, and are the sort of pieces where verses can easily be swapped around from version to version. As to the song Newsy Woman, a piece that probably began life in the northern woods of Canada and New England, Mark Wilson admits to being at a loss to explain how, or why, such songs travelled so far from their place of origin. But travel they did! Well-known North Carolina singers Frank Proffitt and Bascom Lamar Lunsford both knew versions of Newsy Woman and a Library of Congress recording from Kentucky (here titled I Came to This Country) can be heard on CD3 of the seven CD Yazoo set Kentucky Mountain Music - Yazoo 2200. Over the years I too have been surprised to hear songs that sometimes seemed out of place. When the Scottish Traveller Duncan Williamson said that he would sing me The Devil and the Farmer's Wife I was not expecting to hear a version of the ballad that had come all the way from the Appalachians! But Duncan had met people from all over the place (his second wife was from America) and so it should not really have been such a shock when he started singing.

Nimrod Workman, in common with many other tradition singers, had a number of sentimental songs that he liked to sing. The Drunkard's Lone Child and Little Bessie are showcased here. He also knew and sang quite a few religious songs, a practice followed by many Appalachian singers. Clearly the church, in its many manifestations, has played an important part in the formation of Appalachian societies. Some of these songs, such as The City Four Square, The Stone that was Hewed Out of the Mountain and Little David Play on Your Harp were shared by both black and white singers, as was the song Oh, Death (Roud 4933), which is possibly best known from the recording made by Dock Boggs. It now seems almost mandatory to begin any note about the song Oh, Death with a comment about the early English song Death and the Lady (Roud 1031). But, as Mark Wilson correctly observes, they are not the same song. Mark also briefly comments on claims for 'ownership' of this song; a subject that clearly saddens him. If you are confused by Mark's note and want to learn more, then have a look at Carl Lindahl's article 'Thrills and Miracles: Legends of Lloyd Chandler' published in the Journal of Folkore Research (Indiana University Press) 41, pp.133 - 171, to see what the fuss is all about.

I never met Nimrod Workman. I only know of him through his recordings, and from his appearance in a few films. He seems to have been an extrovert person whose character took over when he was singing. Some of his neighbours found this odd. "Oh, he was just acting a fool for the hippies", they would say. Well, singers come in many shapes and sizes. Some, like Walter Pardon, stood impassive as they sang. Others, like Nimrod Workman, seemed to perform with their whole body. And this intensity does come out in these fine recordings. Thank goodness that Nimrod Workman was only too happy to let Mark Wilson record him, and that Mark Wilson was happy to share these recordings with us. Nimrod Workman's Mother Jones' Will is certainly heading up my list of the year's outstanding albums.

Mike Yates - 9.5.11

Wiltshire

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |