|

Tracks 1/2 | Title The Swansea Hornpipe | Duration 1:12 / 0:40 |

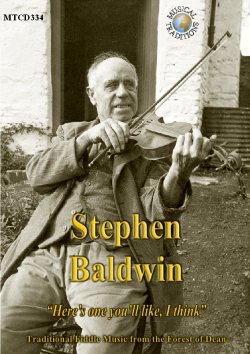

Musical Traditions Records' second CD release of 2005: Stephen Baldwin: "Here's One You'll Like, I Think" (MTCD334), is now available. See our Records page for details. As a service to those who may not wish to buy the record, or who might find the small print hard to read, I have reproduced the relevant contents of the CD booklet here.

Tracks 1/2

3/4

5/6

7/8

9/10

11/12

13

14/15

16/17

18

19

20/21

22/23

24

25

26

27/28

29

30/31

32/33

34.35

36

37/38

39/40

41

42/43/44

45

46

47/48

49

50

51

52

53

54/55

56/57

58

59

Title The Swansea Hornpipe

Greensleeves

Haste to the Wedding

Flanagan's Ball

The Girl I left Behind Me

The Irish Washerwoman

The Liverpool Hornpipe

The Wonder Hornpipe

Napoleon's Grand March

The Old Brags

Old Towler

Fisher's Hornpipe

Off She Goes

Bonnets so Blue

The Coleford Jig

Tite Smith's Hornpipe

Untitled Polka

So Early in the Morning

The Cock o' the North

Soldier's Joy

The Gypsy Hornpipe

The Flowers of Edinburgh

Rory O'More

The Old Fashioned Waltz

The Winter's Night Schottische

The Polka Mazurka

Pop Goes the Weasel

The Cross Schottische

The Heel and Toe Polka

The Varsoviana 2

The Varsoviana 1

The Morpeth Rant

Highland Fling 1 (Moneymusk)

Highland Fling 2 (Keel Row)

Cabbages and Onions

Pretty LIttle Dear

Just as the Tide was Flowing

Anywhere Does for Me (song)

Duration 1:12 / 0:40

1:08 / 0:42

1:35 / 0:37

1:14 / 0:39

1:13 / 0:37

1:43 / 0.36

1:47

1:48 / 0:40

1:47 / 1:17

0:37

0:53

1:32 / 0:39

1:27 / 0:34

0:44

1:51

1:40

1:48 / 0:40

0:35

1:30 / 0:34

1:16 / 0:38

1:48 / 0:44

0:39

1:38 / 0:37

0:35 / 1:20

1:29

0:44 / 0:54 / 1:43

1:17

0:44

1:39 / 1:10

0:41

2:37

1:52

0:37

0:30

1:56 / 0:37

1:36 / 0:39

2:19

2:15

Total: 72:42

What distinguishes players like these, of course, is their interpretative skills - their ability to harness their own musicality to the individual items in a repertoire to express their understanding of that repertoire.

As in the case of the two musicians I have mentioned, the significance of such recordings is usually acknowledged. Sometimes, however, it is overlooked. Such is the case with the Gloucestershire fiddler, Stephen Baldwin. Despite the fact that he is the only fiddler from the south of England to have been recorded at any great length on more than a single occasion, his recordings have long been less than readily available: a deleted LP on Leader which is (scandalously) no longer available (though a couple of tracks are included in the Topic Voice of the People Series), and a tape on Folktracks, now re-released in an expanded form as a CD, which does not enjoy general distribution. And while the strength of his playing has been recognised, and enthusiasts for an ‘English fiddle style’ have inevitably latched on to him in his uniqueness, it is more often than not his 'lack of practice' or 'poor intonation' which are more generally remarked upon. Perhaps most remarkably, the evidence of his playing seems to have done nothing to dispel the absurd myth that English fiddle style consisted solely of a single rough (unornamented and double-stopped) bow stroke for each note, and even many of his admirers often seem unaware of his importance.

It is hard to overestimate the significance of the recordings which Stephen Baldwin made for the BBC and Russell Wortley in the early 1950s. In its scale, the working repertoire he recorded far exceeds anything else which has been left to posterity by a traditional English fiddler (he also recorded the bulk of his repertoire on two separate occasions). The music and the playing, despite being recorded on equipment which was primitive in the extreme by modern standards, are, as the notes to the Leader LP English Village Fiddler point out, of 'such a quality, and characteristic examples of English fiddle playing are so rare that this becomes a relatively unimportant consideration'.

It is hard to overestimate the significance of the recordings which Stephen Baldwin made for the BBC and Russell Wortley in the early 1950s. In its scale, the working repertoire he recorded far exceeds anything else which has been left to posterity by a traditional English fiddler (he also recorded the bulk of his repertoire on two separate occasions). The music and the playing, despite being recorded on equipment which was primitive in the extreme by modern standards, are, as the notes to the Leader LP English Village Fiddler point out, of 'such a quality, and characteristic examples of English fiddle playing are so rare that this becomes a relatively unimportant consideration'.

It is perhaps - to our great good fortune - the most interesting traditional performers who have left behind them a sizeable body of recorded material. Maybe they alone had the skill to acquire a large repertoire, and the dedication to maintain it, often no longer exploited, or even particularly exploitable, into old age sometimes decades later.

Although these recordings sometimes betray his age, Stephen Baldwin was hardly 'out of practice' when he made them, as has sometimes been suggested. His assured performance on any number of his hornpipes in particular - listen to the Swansea Hornpipe or the Wonder Hornpipe, for instance - is that of an accomplished, exciting and sophisticated fiddler still at the height of his musical powers. And although he may have occasionally been a little rusty on tunes which weren’t among his favourites, his playing is always powerful.

Stephen was the youngest of eight children. His eldest brother, David, was in his early 20s when Stephen was born, and Stephen would have grown up with the youngest of his brothers and sisters. The family lived in Culvert Street in Newent -the southward continuation of the High Street - which was home to several other families of Baldwins and Bowrys, as well as the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel where his mother had been christened in 1835.

Stephen Baldwin worked as a plate-layer on the Great Western Railway for all of his working life. During the First World War he served in France with the 13th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment, the 'Glosters', and was invalided out after the Battle of the Somme. He was twice married. In 1901 he was living with his first wife Mary, who had been born at Mitcheldean and was three years his elder, and their two eldest children at Bilson Green, East Dean, near Mitcheldean. He was survived by his second wife, Grace, who died on 25 January 1960. He had four sons: Reg (described as 80 in 1975, but apparently born in 1900); Charles, 73 in 1975; Alec (b.1901); and Ted; and two daughters, Nora and Olive, from his first marriage. Alec, Nora and Ted all played the banjo, and Ted and Charlie also played the fiddle. Charlie also played the mouth organ and was renowned locally as a bones and spoons player.

Stephen Baldwin inherited his father’s fiddle, which Charles Baldwin had bought at a music shop in Hereford, and he in turn passed it on to his own son Charles, who played it until he was forced to give up when rheumatism stiffened the first finger of his left hand. Stephen Baldwin himself had acquired another fiddle which in later life hung on the wall by the chimney in his cottage at Upton Bishop and is now in the possession of Cambridge Morris Men.

Stephen’s son Charlie would also accompany his father in pubs vamping on the piano, and remembered one such occasion at the Crown in Aston Crews (Herefordshire) when his father suddenly stopped playing and said: “Listen! There’s a wireless; we’re off!” Off they went down the road to the White Hart, where there happened to be a coachload of people from Wales. Stephen and his son Charlie got in by the back door, collected their pints and “soon got going”.

Stephen’s second wife, Grace, also played the piano, and would accompany him when he played the fiddle in the evenings - to discourage him from playing in the pub, it is said; though perhaps maliciously, as many a traditional fiddler also enjoyed playing at home if there was a pianist in the family to play along with.

Charlie Baldwin has suggested that his father wanted to involve him in the recording sessions but could never contact him in time because he could not write (apparently Stephen’s children and his second wife did not always see eye to eye). Given Stephen Baldwin’s apparent preference for a piano accompaniment we can only wonder at our loss.

As well as playing the fiddle and singing popular songs, Stephen Baldwin was also involved in a local carol singing party.

Stephen Baldwin died at home in Upton Bishop on 24 November 1955, having been afflicted with heart problems for some while. Grace Baldwin had nursed him night and day without medical assistance of any kind, and the last thing he said was “Mother” as he died in her arms after his last attack. He was buried at Newent as he had wished, with his medals and a Union Jack (lent by Commander Pope RN of Much Marsh) on his coffin.

Stephen Baldwin died at home in Upton Bishop on 24 November 1955, having been afflicted with heart problems for some while. Grace Baldwin had nursed him night and day without medical assistance of any kind, and the last thing he said was “Mother” as he died in her arms after his last attack. He was buried at Newent as he had wished, with his medals and a Union Jack (lent by Commander Pope RN of Much Marsh) on his coffin.

Charcoal burners, or 'colliers' as they were usually known, would have to bivouac in the woods for days on end, firstly to watch for and repair any cracks which might appear in the turf walls of the 'stack' inside which the wood was burning, and later, once it had cooled, to recover and bag the charcoal, which would then be carted away, on a string of donkeys, to a forge. In the 19th Century charcoal was produced on an industrial basis at factories in the forest. Stephen Baldwin’s father Charles Baldwin himself worked as a charcoal-burner in “the woods belonging to Squire Onslow” near Newent.

In 1871 Newent, 111 miles from London and 9 from Gloucester and by then just outside the Forest proper, had 3168 inhabitants; Newent Union (an old division of public administration) also included Clifford’s Mesne and Bromsberrow Heath. A prosperous town, Newent had been a centre of iron smelting since Roman times, but was also noted for its orchards and the cider and perry they produced, the cheese for which Gloucestershire is famous, and linen.

Nearby Ruardean, once a centre for iron ore smelting furnaces, forges and coal mines, was by comparison depressed. Its inhabitants were equally divided between agriculture and mining/ironworking but, in 1831, 160 people from its 127 families were on poor relief. Perhaps its greatest claim to fame is as the home of the Horlicks family and the birthplace of malted milk

In 1889 - when Stephen Baldwin was 16 - Ruardean acquired an unjust notoriety when its inhabitants were wrongly accused of having set about four French travelling showmen on the road from Cinderford and killing their two performing bears. In fact - as the inhabitants of Ruardean are still quick to point out - they had sought to protect, and then sheltered, the victims. The real culprits were a mob from Cinderford, and those who were eventually arraigned for the offences, described by the court as 'colliers and labourers', included three men called Baldwin, though it should be added that the case against young William Baldwin (15) was dismissed on both counts.

Bromsberrow Heath, which has been on either side of the boundary between Herefordshire and Gloucestershire at different times, was originally a Gypsy settlement on the heath by the separate village of Bromsberrow, and Upton Bishop, where Stephen Baldwin was living when he made the recordings in his 80s, was just over the border in Herefordshire.

In 1910, Charles Baldwin - now living in the almshouses at Newent - was visited by the collector Cecil Sharp, who noted down five tunes from him: Morris Call (the descendant of an already centuries-old tune called Cuckolds All in a Row), Morris March (a version of the Dorsetshire March), the Wild Morris, the Gloucester Hornpipe (a version of the tune more generally known as Nelson’s Hornpipe), and Polly Put the Kettle On (a three-part version of the tune, more elaborate than the familiar one associated with the nursery rhyme). The latter was used for a country-dance whose chief figure was called Diament and involved corner couples swinging.  For some reason Sharp recorded Charles Baldwin’s Christian name as 'George (Charles?)', which perhaps represents a mishearing of Charles as Jarge. Sharp described Charles Baldwin as being 88 in 1910, though he seems to have been christened in 1827 (he was not necessarily christened in his first year of course). According to his son Stephen, Charles Baldwin was 98 when he died. Other tunes which Stephen Baldwin associated with his father included the Liverpool Hornpipe (which Stephen Baldwin had no name for, using that name for both the Wonder Hornpipe and the tune generally known as the Swansea Hornpipe, while using the latter name - on a different occasion - for the Liverpool Hornpipe), and For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow (or For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow with his Trousers On, as his father seemed to have called it).

For some reason Sharp recorded Charles Baldwin’s Christian name as 'George (Charles?)', which perhaps represents a mishearing of Charles as Jarge. Sharp described Charles Baldwin as being 88 in 1910, though he seems to have been christened in 1827 (he was not necessarily christened in his first year of course). According to his son Stephen, Charles Baldwin was 98 when he died. Other tunes which Stephen Baldwin associated with his father included the Liverpool Hornpipe (which Stephen Baldwin had no name for, using that name for both the Wonder Hornpipe and the tune generally known as the Swansea Hornpipe, while using the latter name - on a different occasion - for the Liverpool Hornpipe), and For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow (or For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow with his Trousers On, as his father seemed to have called it).

Before Stephen Baldwin was born his father had played the fiddle for the morris dancers at Clifford’s Mesne (pronounced ‘mean’), just to the west of Newent, until the dancing had stopped in about 1870. It seems likely that Sharp expressed a specific interest in music associated with morris dancing - his great passion at the time - but noted other tunes or versions of tunes which were new to him. None of the five tunes which Sharp noted from Charles Baldwin was in Stephen Baldwin’s recorded repertoire (though one of his hornpipes has been likened to his father’s Morris March). Sharp does not seem to have attempted to get in touch with Stephen Baldwin, probably because he would generally seek out the oldest living sources in the areas he visited.

Morris dancing:

Cecil Sharp had visited the Forest of Dean after meeting the fiddler Henry Allen at Stratford upon Avon on 27 August 1909. Allen, whose age Sharp gives as 90 (probably a rounded up figure as the 1871 Census puts his age at 48) was then living in Mere Street and working the pleasure boats on the River Avon. Henry Allen told Sharp that he had played the fiddle for a set of morris dancers at Ruardean until about 1870, when a man was killed during a fight between rival sets of dancers on Plump Hill (on the road between Mitcheldean and Cinderford). Sharp noted two tunes from Allen, possibly because on this occasion too he was only interested in tunes which were associated with morris dancing. One was a version of Charles Baldwin’s Morris Call, which Allen described as “Calling on - to call ‘em together”, and also described as a march, and the other a Sword Dance, in fact a version of Charlie Baldwin’s Wild Morris. Allen, who was born at Chosen in Gloucester, is described as a 'Musician' in the 1871 Census, while his wife Susannah was an 'Innkeeper' who kept the British Flag public house in Littleworth Street, Littleworth, in Gloucester. The 1881 Census records him as the 'Publican' there, but by 1901 (when his age is given as 80) he was living at Old Stratford in Warwickshire and working as a 'Teacher of Music'.

As a result of this encounter, Sharp immediately paid a visit to the Forest where he met a number of old dancers and musicians, and went back the following year, when he met Charles Baldwin. With its bells and handkerchiefs, the morris dancing of the Forest of Dean seems to have had more in common with the morris dancing of Eastern Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire than with the so-called 'border' traditions of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Shropshire to the north. (Local legend has it that the Clifford’s Mesne dancers, for whom Charles Baldwin played at one time, would dance at Dancing Green in Lea Bailey, where they would drink and play cards. On one occasion as they negotiated the slopes of May Hill - at 900 feet just 100 feet short of being classed as a mountain - en route back to Clifford’s Mesne they were “struck down by a pack of cards from heaven”.) Charles Baldwin also told Sharp that at Clifford’s Mesne the 'flagman' (one of the morris dancers who, as the name suggests, waved a flag) had performed a sword dance (“swords on the ground”) to the tune of Greensleeves.

It was, however, with a border tradition that Stephen Baldwin himself became involved when, at Christmas one harsh winter in about 1897, Thomas Bishop, the 'King' of the morris at Bromsberrow Heath, fetched him over from Newent to stand in for the regular musician, concertina player Bill Rudds, who was ill. Stephen Baldwin was so taken with the dance - which involved two parallel rows of three dancers alternately clashing sticks or stepping in pairs and dancing a figure of eight (a 'six-hand reel') - that he taught it to a side he himself raised at Mitcheldean, where he was living at the time. They danced for two or three seasons until the turn of the century, practising in the clubroom at the George Hotel in Mitcheldean. “There were six dancers, me on the fiddle - I wasn’t above 17 or 18 then - a bit more perhaps, more than 60 years ago, I shall be 80 next birthday. It would amuse the people a lot - anything to amuse ‘em and it amused me to do it".

The tune he favoured for the dance was the Cock of the North, though the dancers at Bromsberrow Heath seemed to have preferred hornpipes, including the Manchester Hornpipe and the Flowers of Edinburgh. When it stopped, the morris at Mitcheldean was one of the last sides to perform, not only in the area but in the country as a whole. In 1950 Mrs Smith, who had kept the Glasshouse, a public house at May Hill, for more than 52 years (and remembered Stephen Baldwin), recalled that the morris dancing at Mitcheldean was “much rougher” than that of the Travelling Morrice, though she added that it was “proper dancing”.

But morris dancing would have accounted for a very small part of Stephen Baldwin’s musical activity. And although he seems to have described a number of standard tunes such as Haste to the Wedding, Off She Goes and the Cock of the North as “morris dances”, they must surely also have been used for country dancing.

(the Seven Steps), Pop Goes the Weasel (which he described as “pretty old-fashioned”), the Varsoviana (two versions). Others seem to have been associated locally with particular dances: The King of the Cannibal Islands (which he called Cabbages and Onions, the alternative title of Double Dee Doubt for the BBC recording suggesting an association with the dance Double Lead Out), the Cock of the North (Cotton Britches/Cock and Breeches), and the Irish Washerwoman (Broomstick Dance). He also described Soldier’s Joy as a “six-hand reel”, and Fisher’s Hornpipe (the Cottage Hornpipe as he called it) as a “three-hand reel”. Stephen Baldwin would have cultivated and maintained these tunes to meet public demand, and the same would be true of his schottisches and waltz.

(the Seven Steps), Pop Goes the Weasel (which he described as “pretty old-fashioned”), the Varsoviana (two versions). Others seem to have been associated locally with particular dances: The King of the Cannibal Islands (which he called Cabbages and Onions, the alternative title of Double Dee Doubt for the BBC recording suggesting an association with the dance Double Lead Out), the Cock of the North (Cotton Britches/Cock and Breeches), and the Irish Washerwoman (Broomstick Dance). He also described Soldier’s Joy as a “six-hand reel”, and Fisher’s Hornpipe (the Cottage Hornpipe as he called it) as a “three-hand reel”. Stephen Baldwin would have cultivated and maintained these tunes to meet public demand, and the same would be true of his schottisches and waltz.

Stephen Baldwin’s friend Bill Williams, the grandson of Jack 'Fiddler' Williams, recounted to Peter Kennedy how he and Stevie Baldwin would go to the clubroom upstairs at the Yew Tree on “the Mitcheldean road” and elsewhere where Steven would play. “The fiddler, he'd sit down in his chair and he'd play the fiddle, you know, and everybody would be having their drink and listening for a time, and then soon as he started on the dancing, see ... up they was and holding one another, and round and round and dancing about there in the club room. Well, I've knowed 'em up there as you couldn't hardly get inside the club room at the Cross, where there were so many people go in there ... of a night. But I can't remember the names on 'em (the dances) now, but of course, I used to enjoy myself all right with 'em”.

Stephen Baldwin recalled being sent for to play for dancing at Whitsuntide in particular, at a time of year when it was “very hot”. He remembered the women dancing to See me Dance the Polka with the “sweat running off of them and their faces as red as their old cotton bonnets”.

On one occasion Stephen Baldwin had been playing at the Yew Tree, but it had got late and he and Bill Williams decided to sleep in the cart house. They settled down in the wagon, but the daughter of the house who slept over the dairy across the yard later described how she had heard Stephen Baldwin playing tunes in the early hours.

One of the dances Bill Williams remembered was called Cotton Britches, and Stephen Baldwin recalled the same dance - which he referred to as Cock and Breeches - being performed at harvest festivals. It was danced by women only, facing each other, who took the hem of their skirts at the back in the right hand, bunched it up and brought it round to the front, while the left hand similarly took the hem at the front round to the back to give the impression of wearing breeches. Then they danced “a kind of Highland Fling” to the tune of the Cock of the North. The Heel and Toe Polka would also be danced to the Sultan’s Polka (now generally known as 1-2-3-4-5; a number of popular dances were associated with what would now be regarded as nursery rhymes).

The other jigs/marches which Stephen Baldwin played, and to an even greater extent the hornpipes, tend to be more complicated - melodically and rhythmically - and his performances of the latter are both more intense and more sophisticated, suggesting they provided greater scope for personal artistic expression. The same dichotomy between simple popular dance tunes played with only sparing ornamentation and more complicated, highly decorated tunes is also apparent, for example, in the playing of traditional Irish players. Fiddlers such as the celebrated Donegal fiddlers Mickey and Johnny Doherty and the great London Irish fiddler Michael Gorman, originally from Sligo, play fast and flashy reels and almost completely unadorned barn dances, quadrilles, schottisches, (highlands or flings) and similar tunes (including the Varsoviana). This seems to have been a characteristic of older fiddlers on both sides of the Irish Sea. Compare also the playing of Ned Pearson in Northumberland, for example.

In England, the hornpipe seems to have filled the niche which came to be enjoyed by the reel in Ireland. Its popularity was obviously tied up with its intrinsic association with step dancing, and hornpipes form the liveliest part of the repertoire of many a traditional musician in southern England. It is, therefore, not by chance that Stephen Baldwin's skill should be most apparent in his playing of hornpipes, which are undoubtedly the most complex and exciting part of his repertoire. The pre-eminence of the hornpipe in Stephen Baldwin's repertoire, for both the fiddler and his audience, is illustrated by the description which he gave to the local collector and antiquarian H H (Harry Hurlbutt) Albino, of a Gypsy wedding he was invited to provide the music for. Arriving at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, he stayed until 2 o’clock in the morning, perched on a tree stump and playing, in his own words, “nothing but hornpipes”, to which the Gypsies danced “with great vigour”. “The sweat simply rolled off them. They never seemed to get tired”.

It is, therefore, not by chance that Stephen Baldwin's skill should be most apparent in his playing of hornpipes, which are undoubtedly the most complex and exciting part of his repertoire. The pre-eminence of the hornpipe in Stephen Baldwin's repertoire, for both the fiddler and his audience, is illustrated by the description which he gave to the local collector and antiquarian H H (Harry Hurlbutt) Albino, of a Gypsy wedding he was invited to provide the music for. Arriving at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, he stayed until 2 o’clock in the morning, perched on a tree stump and playing, in his own words, “nothing but hornpipes”, to which the Gypsies danced “with great vigour”. “The sweat simply rolled off them. They never seemed to get tired”.

As well as the classic hornpipes - the Liverpool Hornpipe, Fisher’s Hornpipe, the Wonder Hornpipe etc - Stephen Baldwin also included a number of rarer items in this part of his repertoire; an indication that a step dancer would respond to the rhythm of a tune while a crowd wanting to dance country dances would respond to a familiar melody. These rarer items were often known by names with local or personal associations (the Coleford Jig, Tite Smith’s Hornpipe). It was quite common for fiddlers to include such items among their hornpipes. James Higgins of Shepton Mallet in the East Somerset Coalfield (b. Bruton, Somerset, in 1819) who Cecil Sharp met and collected from in the Shepton Mallet Union (Workhouse) in 1907, played a number of hornpipes which are otherwise seldom or never found. Among them was one he called the Radstock Jig after the nearby mining town of Radstock, which otherwise seems to be unknown in England (in fact it is a close relation of a tune which appears in O’Neill and has been recorded by traditional Irish fiddlers under the title of Poll Ha’penny, (and is thus a member of a family which also includes Moll(y) MacAlpin/Halpin and Gilderoy, and ultimately goes back to the seminal tune which scholars refer to as Lazarus). This suggests that traditional musicians had much greater - if not complete - freedom in the choice of hornpipes which they added to their repertoires.

At Bromsberrow Heath, Stephen Baldwin was accompanied on the tambourine by Ralph Hill, whose family were closely involved with the morris there. Ralph Hill played the tambourine with his fingers, but told Russell Wortley that Thomas Bishop used a stick. 'Buzzy' Lock (otherwise Leonard Ryles), the son of Fiddler Lock (see below), told Russell Wortley that Thomas Bishop’s stick was 9 inches long, cut from holly, with a knob about 1 inch thick and long at either end. His technique was to strike the tambourine “down” at the “bottom end” and “up” at the “top end”.

At Bromsberrow Heath, Stephen Baldwin was accompanied on the tambourine by Ralph Hill, whose family were closely involved with the morris there. Ralph Hill played the tambourine with his fingers, but told Russell Wortley that Thomas Bishop used a stick. 'Buzzy' Lock (otherwise Leonard Ryles), the son of Fiddler Lock (see below), told Russell Wortley that Thomas Bishop’s stick was 9 inches long, cut from holly, with a knob about 1 inch thick and long at either end. His technique was to strike the tambourine “down” at the “bottom end” and “up” at the “top end”.

In July 1950 Beatrice Hill met the Travelling Morrice at Bromsberrow Heath when they danced there. Later they repaired to the Bell, where Mrs Hill played her “squiffer”, as she called it, and produced a list of tunes she could play. Beatrice Hill’s sister Emily Bishop also played, and accompanied her sister on the tambourine on a subsequent visit by the Travelling Morrice. Russell Wortley corresponded with Beatrice Hill until she died, and sent her a gramophone record of his recordings of Stephen Baldwin. Writing to thank him on 6 April 1955 she said: '… I think it is very good. My sister (i.e. Emily Bishop) and I have listened to it several times on my gramophone …'

In another letter to Russell Wortley dated 29 March 1956 she told him that Peter Kennedy had ' … kindly sent me a BBC record of a few tunes I played on the melodeon…' These were the recordings which Peter Kennedy had made of Beatrice Hill for the BBC at Bromsberrow Heath in 1952, when she played versions of the Nutting Girl, the Cliff Hornpipe (the Herefordshire Breakdown) and Hunting the Squirrel (Nelly’s Tune) on the melodeon. Like Stephen Baldwin, Beatrice Hill was also recorded by Russell Wortley. On 3 November 1954 she wrote to him saying she was '… pleased to hear that the reproduction from the recorder was good…', perhaps a reference to his recordings of her versions of the Manchester Hornpipe and the Three-hand Reel, this latter a tune otherwise recorded from Walter Geary (who diddled it) in Norfolk, and Dennis Crowther of Clee Hill in Shropshire on the mouth organ, likewise without a 'proper' name: it was also recorded in New South Wales from fiddler Charlie Bachelor, who knew it simply as George Parkins’ Schottische. These were all popular tunes, and Hunting the Squirrel seems to have been a particular favourite in the Welsh Marches (Cecil Sharp also noted versions from John Lock(e) and James Lock), but none of them was recorded by Stephen Baldwin).

Another local melodeon player who does have some repertoire in common with Stephen Baldwin was the traveller Lementina 'Lemmy' Brazil (pronounced 'Brazzle'). Like Stephen Baldwin she played the popular (originally Scottish) reel Moneymusk (which she called God Killed the Devil, Oh!) as a “highland fling”, and one of her idiosyncratic hornpipes seems to be a version of his equally idiosyncratic Gypsy (College) Hornpipe. She spent many years travelling in Ireland when she was young and came from a much-recorded family of singing travellers.

Stephen Baldwin was obviously in contact - directly or indirectly - with the gypsy fiddler 'Tite' (Titus?) Smith. Like Henry Allen, Tite Smith played for the morris dancers at Ruardean; in his day the tunes used there were Speed the Plough, Soldier’s Joy, Haste to the Wedding, and Greensleeves. Stephen Baldwin played a hornpipe (included here) which bears his name. At Ruardean he succeeded fiddler Paddy Morgan of Walford or Kerne Bridge, in Herefordshire, who, according to his granddaughter Mrs Creed, was a “great musician”. He was also remembered for the black peppermint tea he made! Paddy Morgan may have been related (or identical) to the fiddler Theophilus Morgan, of Goodrich, and a 'Fiddler' Morgan was said to have kept the Crown Inn at Howle Hill. All of these places are very close to each other. Despite his nickname, Paddy Morgan was apparently not related to the Irishman Sam Morgan whose wake was held at Dancing Green.

Also at Ruardean, a Mrs Thompson told Russell Wortley that the only remaining member of the morris dancers left in the district was the musician, a fiddler known as 'Croogy' Bennett, who lived on the hill to the south of the village. Apparently he did not like being called “Croogy”!

A celebrated fiddler from an earlier generation who was still remembered locally was Jack 'Fiddler' Williams of Gonders Green, who had played for a set of morris dancers at May Hill. He is said to have played Greensleeves for the pipe dance (performed over a pair of crossed churchwarden pipes on the ground) and a clapping dance. His father had played before him, and he passed his fiddle on to his own son, who didn’t play it, however. When he died in about 1925, his son sold his fiddle to Goddard’s music shop in Gloucester for '£5 + £1', after 'successful repairs'. It was subsequently sold for £50 (or £200 in another account). Yet another account had his fiddle swapped for a suit of clothes. A Mr Bevan at Gonders Green was also said to be a fiddler.

He is said to have played Greensleeves for the pipe dance (performed over a pair of crossed churchwarden pipes on the ground) and a clapping dance. His father had played before him, and he passed his fiddle on to his own son, who didn’t play it, however. When he died in about 1925, his son sold his fiddle to Goddard’s music shop in Gloucester for '£5 + £1', after 'successful repairs'. It was subsequently sold for £50 (or £200 in another account). Yet another account had his fiddle swapped for a suit of clothes. A Mr Bevan at Gonders Green was also said to be a fiddler.

Another local fiddler, who told Russell Wortley that he had often heard Charles Baldwin play, and had played with Stephen Baldwin (whom he worked with when young), was farmer John Lewis of May Hill. They had played their fiddles together for parties etc, often all through the night, and he recalled one week when they had only got nine hours sleep all told. Having had lessons on the fiddle himself, he said that Stephen Baldwin had learnt entirely by ear.

Charles Baldwin knew and played with Fiddler Lock, from Gorseley, perhaps a relation of, or identical to, the celebrated gypsy fiddler John Lock(e), whom the local folklorist Ella Leather encountered duetting with his brother on the fiddle at Pembridge Fair in Herefordshire, and subsequently recorded on wax cylinders. A recording on wax cylinder of a fiddler playing a hornpipe which was found in the vaults of the Vaughan William’s Library at the Headquarters of the EFDSS in London has been associated with that occasion. Mrs Leather introduced John Lock(e) to Cecil Sharp, who noted down some of his tunes at Leominster in January 1909, and some from Mrs Leather’s wax cylinders. John Lock(e) was eventually forced to give up fiddling by the occupational hazard of rheumatism in his fingers.

The Locks were renowned fiddlers: John Lock had learnt many of his tunes from his father Ezekiel ('Zekie') Lock, and his Uncle Noah. John himself was said to be the best of a number of fiddling brothers, one of whom may have been the 'Polin' Lock who was found dead in the snow with his fiddle (which was buried with him) near Church Stoke, Montgomeryshire, in about 1928. Another of Sharp’s sources, James Lock, then living at Newport in Shropshire, may also have been related, as may 'Winkles' Locke, “the best of all gypsy fiddlers” according to Jack Locke, the son of another Noah Locke. The Baldwins were themselves said by some locally to have been of gypsy stock - even as far as being described as “didikies” by one source - and related to the Locks and the Ryles, but local parish records and registers indicate that the Baldwins - and there were many families bearing that name in the Forest - had been settled at Newent and Ruardean for generations.

Although, like Stephen Baldwin, the Lock(e)s were great hornpipe players, that part of their repertoires doesn’t coincide, unless the Boy’s Hornpipe, which Stephen Baldwin’s second wife remembered him playing, is a reference to the Boyne Water as played by John Lock (a name which has been recorded elsewhere as the Boy in the Water, or even the Boiling Water!)

The overall picture is one of dense traditional musical activity - and fiddling in particular - on Stephen Baldwin’s doorstep in his own and earlier generations.

Notations of many of the tunes associated with these musicians (including Stephen Baldwin) are included in the collection The Coleford Jig, compiled by Paul Burgess and Charles Menteith (self-published, 2004).

A couple of months later he returned with the Travelling Morrice and, on 28 June 1947, they visited Stephen Baldwin at Upton Bishop, piling into his drawing room until it was seething with people. Stephen took his rosin-covered fiddle down from its hook near the mantelpiece and played Flanagan’s Wake (sic! - presumably a reference to Flanagan’s Ball), Cock o’ the North, Flowers of Edinburgh, Gypsy(’s) Hornpipe, Swansea Hornpipe, Liverpool Hornpipe, Doublededout (Humpty Dumpty), a “particularly fine” version of Haste to the Wedding and Greensleeves. He also tried, though on this occasion unsuccessfully, to remember Moneymusk. Everyone then went into the garden where the Travelling Morrice performed the six-hand reel which Stephen Baldwin had adopted from the dancers at Bromsberrow Heath, watched by locals and children while he played the Cock of the North. H H Albino also visited Stephen Baldwin on 3 October 1947, when he played Haste to the Wedding, the Gypsy’s Hornpipe, Moneymusk, Double Di Doubt, the Liverpool Hornpipe, and He’s a Jolly Good Fellow with his Trousers On, as his father had called it.

A couple of months later he returned with the Travelling Morrice and, on 28 June 1947, they visited Stephen Baldwin at Upton Bishop, piling into his drawing room until it was seething with people. Stephen took his rosin-covered fiddle down from its hook near the mantelpiece and played Flanagan’s Wake (sic! - presumably a reference to Flanagan’s Ball), Cock o’ the North, Flowers of Edinburgh, Gypsy(’s) Hornpipe, Swansea Hornpipe, Liverpool Hornpipe, Doublededout (Humpty Dumpty), a “particularly fine” version of Haste to the Wedding and Greensleeves. He also tried, though on this occasion unsuccessfully, to remember Moneymusk. Everyone then went into the garden where the Travelling Morrice performed the six-hand reel which Stephen Baldwin had adopted from the dancers at Bromsberrow Heath, watched by locals and children while he played the Cock of the North. H H Albino also visited Stephen Baldwin on 3 October 1947, when he played Haste to the Wedding, the Gypsy’s Hornpipe, Moneymusk, Double Di Doubt, the Liverpool Hornpipe, and He’s a Jolly Good Fellow with his Trousers On, as his father had called it.

The Travelling Morrice next visited Stephen Baldwin on 27 June 1950, when he again played for them. He played Greensleeves, which he described as “one of the oldest there is; my father said it was an old tune in his time”. The Travelling Morrice visited him again in 1952, on which occasion Stephen Baldwin played the Cock of the North with Rollo Woods, fingering the tune in A while playing in G (he tuned his fiddle in the old-fashioned way, a tone below concert pitch) to accommodate the “novice concertina player” as Woods described himself.

Later in 1952 Rollo Woods met Peter Kennedy of the English Folk Dance and Song Society at its headquarters in Cecil Sharp House in London, and advised him to visit Baldwin in Upton Bishop, and also Beatrice Hill and Emily Bishop at Bromsberrow Heath. Peter Kennedy had been commissioned by the BBC to record traditional music in the field, and he recorded several of Stephen Baldwin's tunes in the schoolroom at Upton Bishop on 13 October 1952. One of these was broadcast on Peter Kennedy’s radio programme As I Roved Out, which was devoted to field recordings of traditional music, and this made a local celebrity of Stephen Baldwin.

The Travelling Morrice last visited Stephen Baldwin in 1954, a year before his death in November 1955. It was during this visit that the recordings made by Russell Wortley which appear on this CD were made on Tuesday 22 June 1954.

The recordings were made on a Grundig tape recorder - using what was described at the time as 'Scotch Boy specially prepared magnetic tape' - in the headmaster’s study in the village school, which was cramped, but the only source of mains electricity in the village. (It was also open as usual on the day the recordings were made, and the children can be heard going out to play while Stephen Baldwin plays Off She Goes). Dr Wortley held the microphone in a convenient position while Stephen Baldwin “played tune after tune with little prompting”. Baldwin’s playing was “almost continuous”, and Rollo Woods remembers that “our efforts that day were focussed on getting as many tunes from him as possible and, once he was in full flight, not to stop him”.

Altogether, some 39 different items of repertoire, including one song, were recorded from Stephen Baldwin, and the names of a further 30 were provided by his widow after his death (though a few of the latter are, or may be, different names for tunes which he recorded). The list of tunes which Stephen Baldwin recorded for Russell Wortley is almost identical to the list of those he recorded for Peter Kennedy, and Moneymusk and the Flowers of Edinburgh, which were only recorded by Peter Kennedy, are also mentioned among the tunes which Stephen Baldwin played for Russell Wortley and the Travelling Morrice on a previous occasion.

The list of tunes which Stephen Baldwin recorded for Russell Wortley is almost identical to the list of those he recorded for Peter Kennedy, and Moneymusk and the Flowers of Edinburgh, which were only recorded by Peter Kennedy, are also mentioned among the tunes which Stephen Baldwin played for Russell Wortley and the Travelling Morrice on a previous occasion.

Some of the performances on the earlier recordings, made by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1952, are both more relaxed and more immediate than the later ones made by Russell Wortley in 1955, which may show signs of his failing health, including neuritis in both hands and arms (Stephen Baldwin was to die the year after the later recordings were made). However, he did benefit from the opportunity which the later recordings gave him to play his tunes through more than once (which is generally all we get on the BBC recordings). In most cases his performance improves each time through, as he finds his old touch, and by the third (and usually final - apparently his own choice) time through he is playing with confidence, composure and obvious enjoyment.

The tunes:

Stephen Baldwin’s recorded repertoire includes a number of tunes in 6/8 (which were probably regarded as marches rather than jigs), highland flings, schottisches, tunes associated with particular country dances and couple dances, some associated with solo dances, and a number of hornpipes.

Marches

Many of the standard tunes which Stephen Baldwin played were and are familiar marches used by the British Army, many of which had been adopted for use with quadrilles in the early part of the 19th century. These include Haste to Wedding, the Cock of the North, the Irish Washerwoman, Rory O’More, Bonnets o’ Blue and Brighton Camp. Two of Stephen Baldwin’s marches which have never been in general circulation among traditional English musicians have local associations: the Kinnegad Slashers was the regimental slow march of Baldwin’s own regiment, the 'Glosters' (the Gloucestershire Regiment), who inherited the nickname of the Old Brags from the 28th Regiment of Foot, and Old Towler was the regimental march of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry. And Men of Harlech, the first tune which Stephen Baldwin learnt from his father, was the regimental march of the South Wales Borderers.

Hornpipes

The Wonder Hornpipe, Swansea (“Gloucester”) Hornpipe, Fisher’s (“Cottage”) Hornpipe (“Here’s one you’ll like, I think”), Liverpool Hornpipe (“very old”) and Flowers of Edinburgh were the backbone of the step-dancer’s repertoire and most of them have spread around the English-speaking world in that capacity. The Morpeth Rant is found occasionally throughout England but otherwise seems not to have travelled much from its home in the northeast. On the recording he starts the tune three times in different keys, each time perfectly, before settling on the one in which he felt most comfortable.

There is a considerable disparity among the names which are applied to the hornpipes which Stephen Baldwin recorded (and his father played) on different occasions, but as Stephen Baldwin told Russell Wortley on recalling the name of the Coleford Jig: “but of course it’s a bit of a job to know all their names”.

There are some notable omissions from this part of Stephen Baldwin’s repertory, including some of the otherwise most popular hornpipes: Manchester (Yarmouth /Rickets) Hornpipe, Cliff(e) Hornpipe, College Hornpipe (Sailor’s Hornpipe/Jack’s the Lad) and Londonderry Hornpipe (usually known as the Breakdown, preceded by a local place-name). His wife did include a Sailor’s Hornpipe in a list of tunes he knew, but it is not known which tune this refers to. The Manchester Hornpipe and the Cliff Hornpipe were known in this area, and were collected from Beatrice Hill at Bromsberrow Heath.

There are also some rarely-heard or apparently unique hornpipes in Stephen Baldwin’s recorded repertoire: the Coleford Jig, Tite Smith’s Hornpipe and the tune which Stephen Baldwin variously called the Gipsy’s, College or Gloucester Hornpipe.

Highland Flings

Two of Stephen Baldwin’s tunes - Moneymusk and what may be a version of the Keel Row - are described in the notes to the BBC recordings as 'Highland Flings'. These were once an important part of the traditional repertoire in England and Ireland (where they were known simply as 'Highlands' in Donegal and 'Flings' elsewhere). Stephen Baldwin recalled a dance “like a highland fling” performed by women at harvest festivals.

Moneymusk was originally a Scottish reel but, with the exception of what Paul Roberts has described as the 'hits' (Miss McLeod, the Duke of Perth, the Fairy Dance, etc.), reels as such are seldom found among traditional English musicians, perhaps because the slot for fast tunes in duple time was already dominated by the classic English metre, the hornpipe. The only example in common circulation in modern times seems to have been the Rakes of Mallow (not always under that name), which may pre-date the reel as a fixed type of tune.

Baldwin is very much an 'off the string' (détaché) player. That is to say he applies a minimum of pressure to the bow, which consequently 'skates' across the strings. The effect is particularly striking in single-bowed runs up or down the scale, and in rocking alternation between adjacent strings). Baldwin supplies the control which this 'skating' effect necessitates (and which is otherwise supplied by means of a more tense articulation) by playing spiccato, a light staccato. In Ireland, the old Clare fiddler Patrick Kelly played in a similar way, while the later Clare player Bobby Casey has a similar musical style to that of Kelly, but distinctly 'on the string'. The tense 'on the string' way of bowing may have been adopted from more formal violin styles which came to the fore in traditional music after Baldwin and Kelly had already developed their styles.

Baldwin is very much an 'off the string' (détaché) player. That is to say he applies a minimum of pressure to the bow, which consequently 'skates' across the strings. The effect is particularly striking in single-bowed runs up or down the scale, and in rocking alternation between adjacent strings). Baldwin supplies the control which this 'skating' effect necessitates (and which is otherwise supplied by means of a more tense articulation) by playing spiccato, a light staccato. In Ireland, the old Clare fiddler Patrick Kelly played in a similar way, while the later Clare player Bobby Casey has a similar musical style to that of Kelly, but distinctly 'on the string'. The tense 'on the string' way of bowing may have been adopted from more formal violin styles which came to the fore in traditional music after Baldwin and Kelly had already developed their styles.

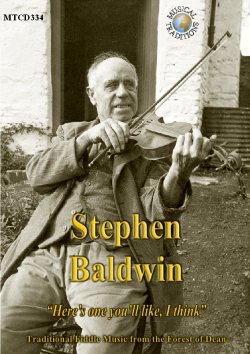

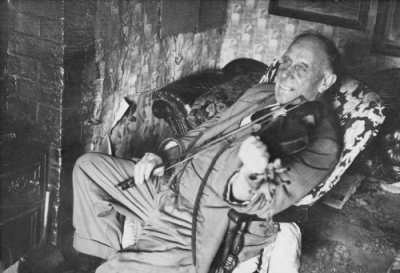

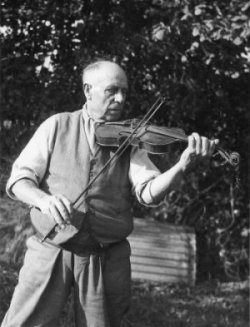

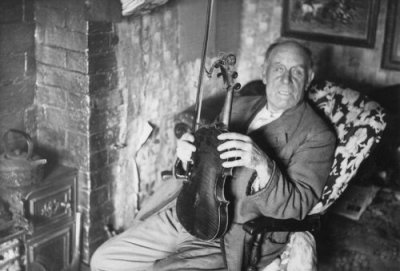

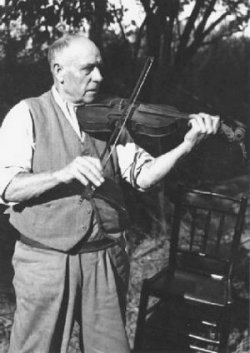

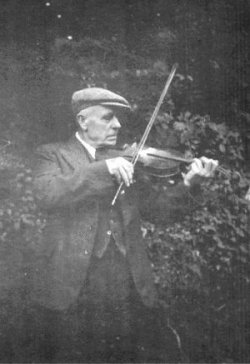

The control and rhythmic complexity which Stephen Baldwin was able to achieve using this articulation suggest that he played mainly from the wrist, and this is borne out by all the existing photographs - albeit posed - of him playing, which show the elbow of his bowing arm tucked in and pointing down. The photographs also suggest that he played towards the tip of his bow, unlike other Gloucestershire fiddlers like William Hathaway and John Mason, whom photographs show with their elbows tucked in but playing near the frog end of the bow. Baldwin also pushed his little finger between the hair and the stick of the bow, with his other three - huge - fingers resting on top of the stick. The position of the little finger in particular has a considerable stabilising effect on the bow, and the same hold is apparent in photographs of many, if not most, traditional fiddlers in southern England, including Herbert Smith in Norfolk and Henry Cave in Somerset, for example. Although he played with both elbows tucked in, like most traditional fiddlers in England, he held the fiddle itself in a horizontal position and not dropped on to his chest.

With this 'off the string' style of bowing, there is a danger that the bow will bounce uncontrollably if a sequence of notes is bowed in the opposite direction to that in which the player is accustomed to playing that sequence, and this is just what happens in Baldwin's later recording of Fisher's Hornpipe. The second time through he finds himself bowing the first half of the 'A music' (the first strain) the 'wrong' way (from his point of view) - to devastating effect. To compensate he plays the A music a third and extra time, this time the 'right' way. The fact that this could happen is an indication of Baldwin's accomplishment, rather than a sign of any lack of proficiency. It was only his practice and experience which could have fixed such a complex approach to a tune so decisively in his mind (or rather his wrist). It is also a sign of his musical savvy that he should immediately have understood the error, and corrected it.

With the exception of Northumbria and East Anglia there are too few recordings of traditional fiddlers in the different regions of England to look at Stephen Baldwin in the context of a regional or local style. If, however, the wax cylinder in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library is of John Lock, fiddlers in this part of the country may have played in a freer, more relaxed manner than their counterparts in Norfolk for instance, where fiddlers like Herbert Smith and Walter Bulwer used the same techniques involving back bowing and cross bowing as Stephen Baldwin, but adopted a more rigid, almost Scottish, approach to tempo. But it should not be imagined, of course, that either approach to playing is necessarily indicative of an old or established regional style. It is just as likely that they reflect the contemporary preferences of influential local musicians.

(a) Stress:

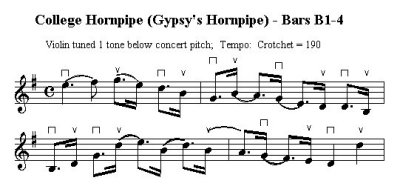

The subject of stress in English traditional music is a complex one. English musicians play very much 'vertically ' by the rhythm of a tune rather than 'horizontally' by its pulse (unlike modern Irish players, for example). While the main stress is typically on the off-beat, the first beat of the bar in duple time tunes also carries a subsidiary stress. In hornpipes, the characteristic bom-bom-BOM of every eighth bar in fact informs the stress of every bar (other than the first usually: see below). At the same time, Baldwin, like most traditional musicians in England, habitually employs a form of syncopation (in the true sense of the word) by stressing the very first beat of a strain or phrase -  which sometimes optionally absorbs the notes which immediately follow it - before transferring the main stress to the off-beat for the remainder of the strain. This approach also characterises the recorded playing of such players as Lewis 'Scan' Tester, Billy 'Jingy' Wells, George Craske and William Kimber, for example, and can also be identified in Cecil Sharp's notations of an earlier generation of fiddlers, including James Higgins, and Stephen Baldwin’s father Charles. The most familiar universal example of this feature is the very first bar of the first strain of the Morpeth Rant. A good example of this in Stephen Baldwin’s recordings is the first bar of the second strain of his College Hornpipe (Wortley) / Gypsy’s or Gloucester Hornpipe. (BBC).

which sometimes optionally absorbs the notes which immediately follow it - before transferring the main stress to the off-beat for the remainder of the strain. This approach also characterises the recorded playing of such players as Lewis 'Scan' Tester, Billy 'Jingy' Wells, George Craske and William Kimber, for example, and can also be identified in Cecil Sharp's notations of an earlier generation of fiddlers, including James Higgins, and Stephen Baldwin’s father Charles. The most familiar universal example of this feature is the very first bar of the first strain of the Morpeth Rant. A good example of this in Stephen Baldwin’s recordings is the first bar of the second strain of his College Hornpipe (Wortley) / Gypsy’s or Gloucester Hornpipe. (BBC).

See example: Gypsy’s Hornpipe

(b) Phrasing:

This cuts across the formal bar-boundaries of conventional notation (this has ever misled those who try to play traditional music from notation alone).

(c) Tempo:

Stephen Baldwin's playing is at times quite fast: he plays hornpipes and jigs presto (between about 168 and 200 beats per minute). On the Folktrax 115 CD the same tunes are played prestissimo, and a tone sharper; however, it now clear that these recordings had been speeded up at the time they were transferred to CD format. This is now corrected here, and all the tunes should be in their original keys and tempi.

(d) Bowing:

It is in Stephen Baldwin's bowing that his skill is most apparent. Far from being composed solely of single bow strokes, it is made up of alternating passages of single bow strokes and slurred passages which cross bar and also phrase boundaries.

This pattern of bowing is a feature of all of Baldwin's hornpipes. Subject to minor variation, the pattern is repeated each time he plays through an individual tune.

A similar style of bowing is described in William Honeywell's Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. Honeywell makes a distinction between a 'Sailor's Hornpipe' style ('almost identical with that of bowing reels'), and a 'Newcastle style' ('used for clog dancing or other step dancing'), the latter being characterised by constant and consistent bowing across phrase boundaries.

Honeywell also describes a third way of playing hornpipes, the 'Sand Dance Style', which features single bowing - 'pianissimo' - throughout, the first bow of each bar - and from then on every other bow - being an up-bow.

While the effect of the 'Sailor's Hornpipe' style is rather sluggish, 'Newcastle' bowing has an obvious capacity to lift a tune, though the effect of strict (and constant) Newcastle bowing is ultimately tedious (though not unknown among traditional fiddlers).

Honeywell also describes a 'mixed' style, which combines 'Newcastle' bowing with 'Sand dance style' bowing.

Stephen Baldwin’s style mixes elements of 'Newcastle' bowing with its slur onto the beat (main beat and off-beat - 'cross-bowing') with straightforward single bowing - which is particularly apparent in runs - (he generally avoids the all-too-obvious slur off the beat which features in Honeywell's 'Sailor's hornpipe' style and is general in other types of music) to create an effect of dynamic variation. But perhaps more significantly, certainly more distinctively, his slurs are bowed against the expected direction, that is to say he plays his slurs onto the beat with an up-bow - as in Honeywell's 'Sand dance style' ('back-bowing').

Stephen Baldwin’s style mixes elements of 'Newcastle' bowing with its slur onto the beat (main beat and off-beat - 'cross-bowing') with straightforward single bowing - which is particularly apparent in runs - (he generally avoids the all-too-obvious slur off the beat which features in Honeywell's 'Sailor's hornpipe' style and is general in other types of music) to create an effect of dynamic variation. But perhaps more significantly, certainly more distinctively, his slurs are bowed against the expected direction, that is to say he plays his slurs onto the beat with an up-bow - as in Honeywell's 'Sand dance style' ('back-bowing').

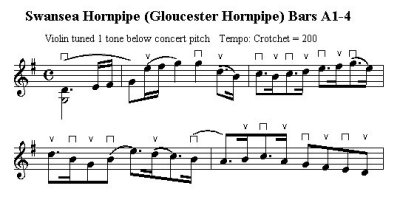

See example: Swansea Hornpipe

(e) Dotting:

It is often said that English fiddlers do not play hornpipes 'dotted', but this is presumably a way of describing the fact that they play them quite quickly, rather than at the tempo of a schottische like an Irish fiddler might, for 'dotting' is one of the distinctive features of English hornpipe-playing. Stephen Baldwin preserves what I have described as the 'vertical stress' of his duple-time tunes by playing the first and third quavers of a bar 'dotted' (and thus followed in each case by a semi-quaver), and the fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth quavers of a bar undotted. This he does sympathetically rather than with monotonous regularity, and he sometimes reverses the pattern (dotting only the fifth and seventh quavers) when it suits the phrasing. A similar technique is apparent in his playing of jigs and 6/8 marches: he often dots the first quaver in the first set of three notes in a bar (making the next note a semi-quaver), and plays the second set of three quavers as just that. Once again, he sometimes reverses the pattern, dotting only the fourth quaver in a bar, particularly when it is phrase-final.

As we have already seen, Stephen Baldwin had a very large repertoire. It was also quite varied, comprising hornpipes, jigs, marches, country-dances and tunes for morris dances, as well as some song tunes (the majority of the latter surviving only as names on the list provided by his widow). The 'morris dance tunes' are not specific to that purpose (they include Brighton Camp, Haste to the Wedding, etc), but they are generally speaking relatively simple (and popular) tunes.

The 'morris dance tunes' are not specific to that purpose (they include Brighton Camp, Haste to the Wedding, etc), but they are generally speaking relatively simple (and popular) tunes.

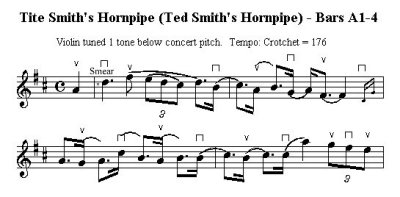

I have described some of Stephen Baldwin’s tunes as 'idiosyncratic'. This is certainly true of his Gypsy’s Hornpipe, but probably none is more so than the tune he called Tite Smith’s Hornpipe. Of course some of the idiosyncrasy evident in this tune may be laid at the door of Tite Smith himself, but to my mind it is necessary to understand and appreciate the more unusual items in Stephen Baldwin's repertoire to the point where they seem completely normal, before his approach to the more standard items can be appreciated properly.

Example: Tite Smith’s Hornpipe

Philip Heath-Coleman - July 2005

Notes on the tunes:

The tunes are listed by the title which Stephen Baldwin himself seems to have used, or by their ‘usual’ (or a distinctive) name if he used either more than one name for a single tune, the ‘wrong’ name, or just a generic name, such as ‘(Irish) Jig’. Each note is followed by an indication as to whether it was recorded by Russell Wortley (RW) or by Peter Kennedy for the BBC (BBC + the number of the original BBC record), or both, with the name it was given at the time of the recording(s) (‘within quotation marks’) if different from the name used in here.

1/2 - The Swansea Hornpipe appears in old fiddler’s tune books from all round the country, usually under that name, though O’Neill published it with an Irish name - the Man from Newry. Although most published versions from England - and the odd recorded one - are in the key of D, Stephen Baldwin fingered it in G (but played it in F, his fiddle being tuned a tone below concert pitch), which seems to suit the fiddle better, and is also the key used in O’Neill. When he played it for Peter Kennedy he called it the Liverpool Hornpipe, and when he played it for Russell Wortley he called it the Gloucester Hornpipe (the name his father, Charlie Baldwin, used for Nelson’s Hornpipe). (BBC 18680 ‘Liverpool Hornpipe’; RW ‘Gloucester Hornpipe’)

3/4 - Greensleeves was often found among English traditional musicians in this form, and frequently used for a solo dance performed over crossed churchwarden pipes, flails or, as described by Charles Baldwin, swords. (BBC 18680A; RW)

5/6 - Haste to the Wedding originated on the 18th century stage as the title song of a light opera called Rural Felicity. Thanks to the phrase which soon replaced its original title, it came to be used at weddings by bell ringers throughout the country. A favourite march of the 15th/19th King’s Royal Hussars, it was probably England’s most popular ‘jig’ until the Cock of the North usurped that position. (BBC 18680A; RW)

5/6 - Haste to the Wedding originated on the 18th century stage as the title song of a light opera called Rural Felicity. Thanks to the phrase which soon replaced its original title, it came to be used at weddings by bell ringers throughout the country. A favourite march of the 15th/19th King’s Royal Hussars, it was probably England’s most popular ‘jig’ until the Cock of the North usurped that position. (BBC 18680A; RW)

7/8 - Flanagan’s Ball is a name which otherwise generally attaches to the popular jig (more usually known as Lanigan’s - or in Kerr Lannagan’s - Ball) which seems to be a minor version of Smash the Windows. But the first strain of Stephen Baldwin’s tune is strangely reminiscent of the first part of the once ubiquitous Sir Roger de Coverley, the only 9/8 tune which seems to have survived widely in southern English tradition (thanks to the popularity of the dance of the same name with which it was associated throughout the 19th and into the 20th centuries), but here recast in 6/8. His second strain is even more reminiscent of the second part of St Patrick’s Day (in the Morning), a popular dance tune as well as the regimental march of the Irish Guards and other regiments with an Irish association. (BBC 18680A; RW)

9/10 - The Girl I Left Behind Me, otherwise Brighton Camp - has always been popular as a march and dance tune, and is still universally familiar. It was used with the Irish Washerwoman and Rory O’More in the Royal Irish Quadrilles, one of the many sets of quadrilles created by Louis Jullien (1812-1860). The two alternative names occur in a song with which the tune - of early but indeterminate origin - was always associated. It is said to have been played whenever the army struck camp or a ship set sail (BBC 18680A; RW)

11/12 - The Irish Washerwoman seems ultimately to be an English tune which is much older than its current name and was known in the 18th century as the Country Courtship. Stephen Baldwin used it for a broomstick dance. As a march it was particularly associated with the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers. Baldwin’s version is very similar to the one which Cecil Sharp collected from fiddler Dennis Hathaway at Chipping Campden (but originally of Condicote) in northeast Gloucestershire in June 1909, though Mickey Doherty of County Donegal also played a version with a similarly extended compass (BBC 18682A; RW ‘Broomstick Dance’)

13 - The Liverpool Hornpipe: Stephen Baldwin described this as "very old", adding that his father used to play it when he was a child, which may suggest that he first heard some of his other hornpipes when he was older. (RW ‘Untitled Hornpipe 1’)

14/15 - The Wonder Hornpipe is widely known and associated with the celebrated Tyneside fiddler, James Hill (a Scot by birth) who is said to have been born in or around Dundee. Stephen called it the Swansea Hornpipe when he played it for Peter Kennedy, and the Liverpool Hornpipe when he played it for Russell Wortley (BBC 18680 ‘Swansea Hornpipe’; RW ‘Liverpool Hornpipe’)

16/17 - Napoleon’s (Grand) March was popular with traditional musicians throughout the British Isles, and versions have also been recorded from Billy Conroy (whistle) in Northumberland and Billy Pennock (fiddle) of Goathland on the North Yorkshire Moors. George Tremain (melodeon) of Yorkshire recorded it on a 78 rpm record in the 1950s. (BBC 18682B; RW)

18 - The Old Brags was the nickname of Stephen Baldwin’s own Gloucestershire Regiment (the ‘Glosters’), which had inherited it from the 28th Regiment of Foot. The actual name of the tune was the Kinnegad Slashers, and it was the regiment’s slow march (Kinnegad is small town to the west of Dublin, and its Slashers are reputed to have been a local hurling team) (BBC 18682)

19 - Old Towler was originally a song with music composed by William Shield (1748 - 1829), the Gateshead boat builder who rose to become Master of the King’s Music in 1817. It was adopted as the regimental march of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry (53rd Foot) in 1881. (BBC 18682)

20/21 - Fisher’s Hornpipe: “Here’s one you’ll like, I think”, said Stephen Baldwin of the tune he referred to as the Cottage Hornpipe - perhaps a corruption of College Hornpipe - when he played it for both the Travelling Morrice and Peter Kennedy. His is a little different from the standard version - said to have been composed by J Fishar (though there are other claimants) in 1780 - which is otherwise more or less universal. Stephen Baldwin used the tune for a ‘three hand reel’. (BBC 18680B; RW)

22/23 - Off She Goes - now universally known as the tune of the nursery rhyme Humpty Dumpty - was the name by which all traditional musicians used to know this tune, a reference to a movement involving the female dancers in the country dance which it almost invariably accompanied (BBC 18680; RW)

24 - Bonnet so Blue or Bonnets o’ Blue was a country dance tune known at one time to most traditional musicians in England, which was also the regimental march of the Royal West Kent Regiment (BBC 18681A)

25 - The Coleford Jig (its name perhaps originally a reference to the use of this hornpipe for step-dancing in the town of Coleford in the Forest of Dean) seems to share its origins with a tune which O’Neill published as the Honeysuckle Hornpipe. In England the word jig was often associated with solo dancing rather than with the 6/8 metre. (RW)

26 - Tite Smith’s Hornpipe: the name refers to a local gypsy fiddler of that name (which was misheard as ‘Ted’ Smith when the sleeve notes to the Stephen Baldwin LP on Leader were compiled). (RW)

27/28 - Untitled Polka features a device similar to the ‘Scotch snap’ everywhere but where you’d expect it (at the start of a phrase). (BBC 18681; RW)

29 - So Early in the Morning was a popular tune among traditional musicians and the vehicle for a number of songs - including So Early in the Morning - and known elsewhere as In and Out the Windows amongst other things. (BBC 18681B)

30/31 - The Cock of the North was the regimental march of the Gordon Highlanders, and has long been associated - almost invariably combined in a set with the Hundred Pipers - with the dance the Gay Gordons. This is the tune which Stephen Baldwin used with the Morris dancers he assembled at Mitcheldean. Popularly known as Chase me Charlie from the ditty which accompanied the second part, this very old tune (Samuel Pepys mentions an early version, Joan’s Placket is Torn, in his diary for 1667) has over the years acquired both Scottish and Cockney (‘Auntie Mary had a canary …’) associations. (BBC 18680A; RW)

32/33 - Soldier’s Joy was - and is - amongst the most familiar traditional tunes throughout the English-speaking world, though its origins are hazy. Stephen Baldwin was not the only traditional English musician to associate it with a ‘six hand reel’. (BBC 18680, RW)

34/35 - The Gypsy(’s) Hornpipe is a rather idiosyncratic rarity, which bears some resemblance to a simpler stepping tune (‘Tap Dance’) played on the melodeon by Lemmy Brazil. (BBC 18680B ‘Gypsy/Gloucester Hornpipe’; RW ‘College Hornpipe’)

36 - The Flowers of Edinburgh: although the Log of the Travelling Morrice mentions this universal favourite among the tunes which Stephen Baldwin played for them in 1947, the only recording was made by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1952. It is generally attributed (along with many other highly popular ‘traditional’ tunes) to the Scottish composer James Oswald, who was the first to publish it (though not under that name) in his Curious Collection of Scots Tunes in about 1742. He published it again in 1751, in his Caledonian Pocket Companion as a single Flower of Edinburgh. (BBC 18681A)

37/38 - Rory O’More was originally a song by the London-based Irish dramatist and songwright Samuel Lover (1797-1868), concerning the eponymous hero of local resistance to the English settlement of County Laois in the reign of Elizabeth I. Its tune (which Stephen Baldwin referred to merely as an (Irish) Jig) was once extraordinarily popular as a country dance and quadrille tune and a military march (it was the regimental march of the Royal Inniskillen Fusiliers), but the universal familiarity it once enjoyed seems to have faded during the 20th century. (BBC 18682 ‘Jig’; RW ‘Irish Jig’)

39/40 - The Old-fashioned Waltz is a heavily ‘dotted’ version of the tune to the Music Hall song Won’t You Buy my Pretty Flowers. (RW)

41 - The Winter’s Night Schottische was published like much, if not most, of the standard English repertoire, in Kerr’s Merry Melodies (in this case Vol. 2). It was also recorded in Sussex - without a name - from both Lewis ‘Scan’ Tester on the concertina and his friend Bill Gorringe on the fiddle, and in Norfolk from Billy Bennington on the hammered dulcimer and Harry Cox on the fiddle, as well as by Scottish and Irish musicians. (RW ‘Untitled schottische 1’)

42/43/44 - The Polka Mazurka was a 19th century couple dance whose name betrays its affinities. Stephen Baldwin also referred to it as the Plain Schottische, another 19th century couple dance. (RW ‘Untitled schottische 2’; BBC 18682, BBC 18681 ‘(Plain) Schottische’)

45 - Pop Goes the Weasel is the tune for another once universally known country-dance, which seems always to have gone by this name. Another tune which is now universally familiar as a nursery rhyme (RW)

46 - The Cross Schottische was how Stephen Baldwin described the tune and dance otherwise known from its most distinctive feature as the Seven Steps (which also survives as the children’s rhyme Penny on the Water). It seems originally to have been known as the Spanish Schottische and was popular as such in the early 20th century. (BBC 18681B)

47/48 - The Heel and Toe Polka - now instantly recognisable as the nursery rhyme ‘1-2-3-4-5, once I caught a fish alive’ - was the name which traditional musicians usually gave to the Sultan’s Polka as originally composed by Charles D’Albert (1809-1886), resident in London but of a French émigré family, who also assembled many of the quadrilles - including that which is usually known as the Alberts - which swept society in the 19th Century. According to its publishers, Chappel, it ‘has exceeded all other polkas in popularity’. Most traditional musicians played two of the original five parts, but some, like Stephen Baldwin, played a third part in a minor key between the usual two. The popular name refers to the distinctive step of the dance it almost invariably accompanied (BBC 18681B; RW)

49 - The Varsoviana (2) Stephen Baldwin apparently played both this tune and the tune more usually associated with the name (see below) for the Travelling Morrice, but Russell Wortley was only able to record this tune. (RW)

50 - The Varsoviana (1) Stephen Baldwin recorded two tunes by this name; this is the ‘usual’ one, sometimes called the Silver Lake. It was originally a composed piece by Francisco Alonso called the Varsovienne (the name refers to the Polish capital Warsaw) with eight parts, which accompanied a couple dance combining elements of the waltz and the mazurka which swept Europe in the mid 19th century. The tune was known to most traditional musicians in Britain and Ireland, who knew it by variety of names including the Waltz Vienna, and usually reduced it to two parts - not always the same ones. Stephen Baldwin’s version omits the part to which the piece of mnemonic doggerel ‘Cock your leg up’ was sung and which was otherwise more often than not one of the parts played by traditional musicians in Britain and Ireland (BBC 18682)

51 - The Morpeth Rant - a tune attributed to William Shield, which is found occasionally throughout England but generally seems not to have travelled much from its home in the northeast. In the recording, Stephen Baldwin started the tune three times in different keys, each time perfectly, before settling into the one with which he was most comfortable. (RW 'Untitled Hornpipe 2')

52 - Highland Fling 1 (Moneymusk), which Stephen Baldwin plays as what would be called a ‘highland’ in Donegal or a ‘fling’ elsewhere in Ireland, is in origin a Scottish reel, a reworking by the Gows of an older tune by Dow called Sir Archibald Grant of Moniemuske’s Reel. Although it was only recorded by Peter Kennedy, the Travelling Morrice’s log of their visit to Stephen Baldwin in 1947 records that on that occasion he ‘failed to remember Mony Musk’. Lemmy Brazil played a similar version of the tune (which she called God Killed the Devil-Oh!) on the melodeon (BBC 18682A ‘The Highland Fling’)

53 - Highland Fling 2 - which Stephen Baldwin appears to have referred to simply as a ‘country dance’ - seems to be a rather wayward version of the Northumbrian schottische the Keel Row, a name which appears in a list of other tunes Stephen Baldwin knew which his wife made shortly before he died, so he may also have known the ‘standard’ version. Fred Pigeon, the fiddler from Stockland in Devon whom Peter Kennedy also recorded, likewise called his own standard version of the Keel Row a ‘Highland Fling’. (BBC 18682A ‘Highland fling’)

54/55 - Cabbages and Onions - which seems to have been a local name - was widely known among traditional musicians, usually as the King of the Cannibal Isles/Islands. The other name Stephen Baldwin gave to this tune - Double Dee Doubt - suggests it was used for the country-dance known as Double Lead-out. William Kimber called it Hilly-go Filly-go, a name which probably echoes the name of Phillebelula all the Way, a related tune in duple time (BBC 18681A ‘Double-dee-doubt’; RW)

56/57 - Pretty Little Dear is a part of a mnemonic description of the dance figure which was sung to the second part of this tune - which is also the source of an alternative name Step and Fetch Her, though that phrase did not feature in Stephen Baldwin’s version:

Don’t you tease her; try to please her.

That’s what they call the pretty little dear.

The ‘proper’ name of the tune and dance was The Triumph. Stephen Baldwin was not alone in playing just two parts, but the tune usually has three (BBC 18681; RW)

58 - Just as the Tide was Flowing was a once a highly popular ‘folk’ song. An instrumental derivative - the Blue-eyed Stranger - was once equally popular among traditional English musicians, but Stephen Baldwin’s version follows the air of the song very closely. (RW)

59 - Song: Anywhere Does for Me

(Roud 18898)

Well now I'm a married man I am,

Well now I'm a married man I am,

And what a family

For I don't exactly know

But I think there's twenty-three.

Now where to put them all,

Now it's one of my greatest cares

Half a score sleeps on the floor

And a few more up the stairs

And 'tis anywhere does for me,

Oh anywhere does for me

For at 6 o'clock to bed I'm put,

Then they bang me out the foot

And some they wipe their feet

On my ... over me

Well I don't care, anywhere,

It is anywhere does for me.

Now I went home the other day

With pains all over me

And my old girl put me to bed

As quickly as could be.

Now she said “You wants a poultice on

And your pains will soon be gone.”

When she'd mixed up a powder

of mustard 'er said

“John, where will you have it on?”

I says “Anywhere does for me,

Oh it's anywhere does for me

For as long as her makes it nice and hot

I'm not particular about the spot.

Bung it where you like,

Right on my antony

For I don't care, anywhere,

It is anywhere does for me.”

Now I was a-stopping once

When a bleeding fire broke out

I got through the window

And I come to gutter spout

I couldn't see the fire escape

For I was so filled with fright

Went sliding down the gutter

Put the union jack alight.

And 'tis anywhere does for me,

Oh it's anywhere done for dee

Down the spout I had to slide

Then he heard the fireman cried

“Where d'you want the water?”

I said “Here, can't you see?

For I don't care, anywhere,

It is anywhere does for me.”

Now I went to races, well

It's (cleaned!) me out complete

And into the railway carriages

And I got underneath the seat.

Crowds of lovely girls got in,

That made me feel so queer

When one of them looked down and said

“Jack, what are you a-doing there?”

I said “Anywhere does for me,

Oh it's anywhere does for me,

For I've got no money, I'm stoney broke,

To walk home would be no joke.

For I don't mind your muddy boots

As long as I can see,

For I don't care, anywhere,

And 'tis anywhere does for me.”

A music hall song, music by Lilian Bishop, written and performed by Dan Crawley (1872-1912). (RW)

Credits:

All of the foregoing was researched and written by Philip Heath-Coleman. My sincere thanks to Phil, and to all the people who have collaborated with us by providing information, photos, transcriptions, etc.

• John Jenner - (Bagman of the Cambridge Morris Men and Keeper of the Travelling Morrice Archives) for the TM photos. These were taken by several different photographers, but mostly by George Felton. John also provided copies of the Logs of the Travelling Morrice, which were very useful.

• Mrs Diana Hillman - for permission to use Russell Wortley’s recordings.