I’d get him to play before he’d even get his boots off and I can still see him in his big overshoes, playing the fiddle. I guess my first musical claim to fame was that, when he played Pop! Goes the Weasel, I’d make the “pop” with my mouth.

I’d get him to play before he’d even get his boots off and I can still see him in his big overshoes, playing the fiddle. I guess my first musical claim to fame was that, when he played Pop! Goes the Weasel, I’d make the “pop” with my mouth.

I remember fiddle music in the house from the earliest time I can recall. My dad played the fiddle and I can very vaguely remember waiting anxiously for him to get home, so I could get him to play a tune for me. There was a photograph that my mother used to have that shows me dragging the fiddle and the bow with my diaper on, going to the door to greet my father.  I’d get him to play before he’d even get his boots off and I can still see him in his big overshoes, playing the fiddle. I guess my first musical claim to fame was that, when he played Pop! Goes the Weasel, I’d make the “pop” with my mouth.

I’d get him to play before he’d even get his boots off and I can still see him in his big overshoes, playing the fiddle. I guess my first musical claim to fame was that, when he played Pop! Goes the Weasel, I’d make the “pop” with my mouth.

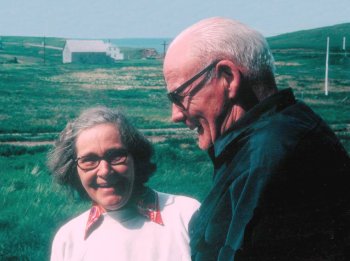

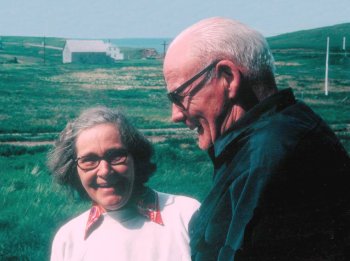

My father, Jerry Sr, was from New Brunswick, born in 1904 in a place just outside of Fredericton called Acton. Acton would qualify as a 'suburb' of Harvey Station, which had a train station and a general store and a few other buildings, while in Acton I don’t think there was anything: maybe just a road sign saying 'Acton'. My mother was from a border town called Saint Pamphile in Quebec, just on the border with Maine. So my mother always kept her French accent. My father’s background, as far as his nationality went, was Irish, although he had a French mother, but not one who spoke French.

From what I’ve understood, it was because of an aunt of mine, my father’s older sister, that they all came to Boston. He had been living in Biddeford, Maine and then fought in the war: he was in the army and then went into the navy. So he did two stints of the service and that’s how he became naturalized and moved to Boston. They had been married about nine years before I was born in 1955. So he was fifty-one when I was born and the kids in school would say, “How come your grandfather always takes you to school?” and I’d answer, “It’s not my grandfather, it’s my dad.”

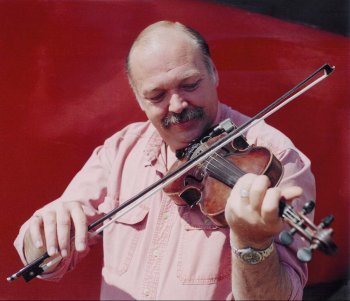

My dad was a sweet, sweet player. He didn’t have a lot of frills in his playing but he had a comfortable drive and you could hear the love he had for music in his playing. He was quite particular about how he played a piece and he put a lot of work into it. He played everything: down east, Irish and Cape Breton. He particularly loved the Cape Breton tunes, the Scottish tunes, and, because of that, he was more focused upon playing the Cape Breton style all the time I knew him and so I never heard him playing with the Irish embellishments, but apparently that was one of the musics that he first fell in love with when he went to Maine. I guess it was Alex Gillis and his Inverness Serenaders that he first heard in Cape Breton music and then later Angus Chisholm and Winston Fitzgerald, obviously. His interest in Irish music became revived a little bit after he met Angus later on because Angus was a big Coleman person. But my father’s single favorite tune was Tom Dey and, every time I play that, I think of him.

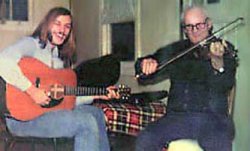

My father had learned a lot of his music from a fellow by the name of Lambert Foley, who would be a relative through marriage. He had four sons and a daughter - Bert, Aubey, Norman, Earl and Winifred - all Foleys, obviously, and all quite musical. Aubey represented a big part of my learning career, generally speaking, because he both gave me encouragement as far as the fiddle goes and taught me to play guitar as a young child. He got me going and kept my interest. He played backup for both my dad and I. And the Landry brothers, Fred and Dan, were good friends of my father, especially Fred.

Another group of early musical recollections that I have center around another friend of my father, by the name of Angus Gillis, who, along with the Foleys, used to come to our house or we’d go to one of their houses, where there’d always be lots of fiddling.  It seemed like every Friday night or Saturday afternoon we’d get together and play some tunes or talk about music and there was always a party possibly once a month or something of that kind.

It seemed like every Friday night or Saturday afternoon we’d get together and play some tunes or talk about music and there was always a party possibly once a month or something of that kind.

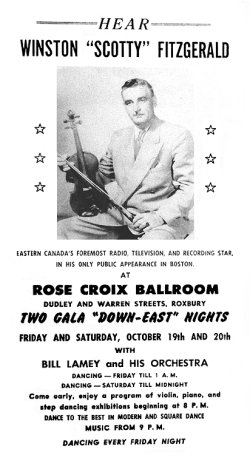

Angus Gillis was originally from Glencoe, Cape Breton and his wife would be a close relation to Angus Chisholm. But all of these households were Canadian-music based in one way or other. Everyone in that group had an interest in fiddle music that was played in the Boston area, whether it came from Cape Breton or from New Brunswick as well: there was quite a mixture of it. One of my first recollections of my 'hero’s music', as I guess I’d call it, was of Winston Fitzgerald coming to the house in about 1958 or so, when I would have been three years old. I had a little small wooden chair and I’m told that I positioned myself so close to Winston to the point where I was almost on top of him. I guess I stared intently at him while he played. He got such a kick out of it that he picked me up and gave me a hug and set me back in my chair. And it seemed like it was only a very short time after that that I woke up and found that all the music was gone and I remember being very upset that there was no music and nobody around the next day. I must have fell asleep in my chair while Winston was playing. And I also remember that I kept looking at his mustache, wondering whether that was dirt on his lip or what the heck it was. I had not ever seen anything like that before and when I later went to Quebec in 1961 or 1962, I saw a lot of fellows with that same kind of a mustache. And I remember thinking, “They all look like Winston.” I saw a lot of Winston in later years when we played together on the television show. He was an incredible character and one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever met. Nothing seemed to bother him and he always had something bright and incredibly witty to say, though I wouldn’t dare write down most of it!

I still remember all the old reel-to-reel tape recorders just covering the kitchen table: the old Webcors and Reveres. A lot of these parties took place at Angus Gillis’ in Rockland, Massachusetts up until the time that Angus moved back to Cape Breton in 1970. Even though I was pretty small - four and five years old - I still have lots of recollections of music back then and can remember how I was impressed by the different players. Little Mary MacDonald, as I recall, was some relation to Angus Gillis and I saw her back then for my first time; I can also remember Angus Chisholm back in that time as well. I can still recollect when Roberta Head’s grandfather, Tom Marsh, came up to Boston from Cape Breton for a visit. He was a good fiddle player but the main thing that got my curiosity as a little kid was the thickness of his glasses: they were very thick and round in a way I hadn’t seen before. I can also still see the kind of overcoat he had on: a light colored overcoat, almost a sand or a beige color.

I can remember Roberta’s aunt even better, Stella, who played piano for Tom. She was a big beautiful woman and she had this beautiful blond hair in the newest style, kind of poofed out with a flip. To me, she looked like a model and I couldn’t take my eyes off of her. And in the same way I remember the first time that I saw Mary Jesse MacDonald, Little Mary’s daughter, who was also a piano player and quite a handsome woman. Well, that didn’t mean an awful lot to a four-year old but it’s funny how looks like that will still impress you as a kid.

My father was a carpenter and he worked at the Veteran’s Hospital as one of the head maintenance men for eleven or twelve years: he once told me that he had laid about eleven square miles of floor tile in the period of time that he was there.  My mother worked there as well in the personnel office. He used to call her just so he could hear her tell the name of her office: she’d answer, “Hello, this is personal” and he got a big kick out of that.

My mother worked there as well in the personnel office. He used to call her just so he could hear her tell the name of her office: she’d answer, “Hello, this is personal” and he got a big kick out of that.

At the age of five my father started teaching me the fiddle. I remember that I thought it was great at first but, after a very short period of time, I thought it was awful: “One finger here - no, not that one - this one; no, not that one, this finger, this one!” And it was also, “No you’ve got to hold it this way - don’t let it drop now - hold it up!” He put an elastic on my hand to help me hold the bow - boy, I hated that. And so it went on in a tortuous way for a time: it’s quite a stretch to start a five years old kid on a full sized instrument. I don’t know if it was my coordination or what the hell it was, but things didn’t seem to want to cooperate at all for awhile. But I finally got so I could play something that was within range of some kind of tune, and then I wanted to learn more and took quite an interest in it. My dad was a nice, sweet player and he taught me all he could and also to listen, appreciate and take notice to what the other fiddlers were doing. He always told me to not copy him but look to somebody that was considerably in better shape, that was a better player, like Winston or Angus Chisholm.

I had learned the guitar from Aubey Foley back then and I had an opportunity to play with Angus Chisholm as far as backing him on a weekly basis. I think I was about ten or eleven when I started that and I did it for about a year and a half or two years. It was in a bar/pub type establishment called Tom Slavin’s, kind of a rough and seedy place down at the end of South Huntington Ave. Was I supposed to be in there? Jeez, I guess not. And it was a long night for a 10-year-old: eight o’clock to eleven or twelve. It was a Sunday night and then I’d have to go to school the next day, but my pay was fifteen dollars a night which was enormous for a kid. The first dance I played at was for Bill Lamey down at the Rose Croix Hall, which was where all the Cape Bretoners went at that time. He ran dances there on a weekly basis and every opportunity that my parents had to take me there, we’d go. The first time I played publicly for Bill I was about six or seven and they had to stand me on a chair so that people could see me. After I was through, Bill picked me up and hugged me. A few years later, Bill started off by letting me play for the first figure of a set and then it became two and eventually it got so I would be playing all three figures of a set. I ended up needing to learn a lot of tunes so that I wouldn’t be playing the same stuff all the time. Bill was very nice to me and was a great inspiration for my playing: I think he was tickled that such a young kid was into the music. O’er the Moor, Among the Heather: that was one of his favorite tunes and I’ve tried to play it here in the way that he liked. And so it all grew from there.

Pretty soon I was getting some exposure as a player. Even starting at around the age of six, I was on some of the local television shows that took place out of Boston: Community Auditions was the name of one of those shows and Starlight on Talent was another. At age seven I danced on Don Messer’s Jubilee: he was a friend of my father’s. Eventually some talent scouts came around for the Ted Mack Amateur Hour which was a popular US national show and I was invited to audition.  I actually did that show three times. That program was quite a scream: as a talent show it was like comparing apples to potatoes or parsnips. There was every kind of a different thing that you were supposedly competing against: everything from a black-faced character who sang Hello Dolly in a top hat and tails to me, who played the fiddle and danced at the same time, which is an act I did back then. I was only at it a short period of time before doing the shows. I had learned how to dance before I played the fiddle, from my father who was a good dancer. I happened to be walking upstairs playing the fiddle one day and my father called me back, “Wait a minute, if you can make it up the steps doing that, you can also dance and play the fiddle at the same. So why not put the two of them together?” And so that’s how all of that started.

I actually did that show three times. That program was quite a scream: as a talent show it was like comparing apples to potatoes or parsnips. There was every kind of a different thing that you were supposedly competing against: everything from a black-faced character who sang Hello Dolly in a top hat and tails to me, who played the fiddle and danced at the same time, which is an act I did back then. I was only at it a short period of time before doing the shows. I had learned how to dance before I played the fiddle, from my father who was a good dancer. I happened to be walking upstairs playing the fiddle one day and my father called me back, “Wait a minute, if you can make it up the steps doing that, you can also dance and play the fiddle at the same. So why not put the two of them together?” And so that’s how all of that started.

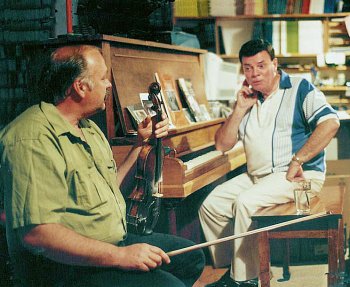

But pretty soon those places like Orange and Rose Croix Hall all closed up and there just wasn’t any place for me to play in Boston between the ages of sixteen and eighteen. So there was a lull in me playing anything on a steady basis of any kind, other than in the summer time when we might come up to Cape Breton. Oh, there’d be things here and there, like the fiddle contests at the French Club out in Waltham.  But little by little a couple of things would come along all of a sudden. One time I got a call to play with a Cape Bretoner at a place called The Harp and Bard, which was an Irish kind of a restaurant-pub. It turned out to be John Allan Cameron and I played the fiddle for him. I think we did just one show, but he was apparently quite taken with me, because the next fall, I got a call to be one of the fiddlers on the pilot for his television show. That first line up was Joe Cormier, Angus Chisholm, myself and Winston Fitzgerald and then, later on, Wilfred Gillis and John Donald Cameron replaced Joe and Angus. Why I got picked, I don’t know. Winston and Angus would have been the two top notches in John Allan’s eyes, but I don’t know how I fit in.

But little by little a couple of things would come along all of a sudden. One time I got a call to play with a Cape Bretoner at a place called The Harp and Bard, which was an Irish kind of a restaurant-pub. It turned out to be John Allan Cameron and I played the fiddle for him. I think we did just one show, but he was apparently quite taken with me, because the next fall, I got a call to be one of the fiddlers on the pilot for his television show. That first line up was Joe Cormier, Angus Chisholm, myself and Winston Fitzgerald and then, later on, Wilfred Gillis and John Donald Cameron replaced Joe and Angus. Why I got picked, I don’t know. Winston and Angus would have been the two top notches in John Allan’s eyes, but I don’t know how I fit in.

But I tell you those television shows offered me a hell of an education in music. I was a poor reader when it came to it: oh, I could read jigs and reels all right, but that was the extent of it. And so I really struggled at different points with that stuff. But what made matters worse was that, in that period of time, there would often be mail strikes in Canada that would stop the written music for the shows from getting to me in time. You see, we’d record the shows in blocks and we’d have to learn a lot of tunes at one time. One time I remember getting a package of sixty to eighty tunes the day when I was leaving for Halifax when I should have gotten the package two weeks before. I didn’t know if I knew any of those tunes or had even heard them before, but I needed to be able to play them as if I had been playing them all my life. And I could imagine the frustration on the part of the other players in trying to get me up to speed on learning this stuff, for they were some of the greatest players Cape Breton has ever known, although they all were very kind and helpful. So I figured the only way I’m going to maintain this job playing with these people is just focus, focus, focus: it was incredible what I endured in that period but I certainly got an education in fiddling because of it. I also had a great interest in expanding my abilities as an accompanist and I learned a lot in that department as well.

When we used to come down to Cape Breton as a teenager, I made up my mind that I was going to live here some day. At that early point, I could see so much potential for the way I wanted to live here and I thought what I wanted to do would be achievable if I came down here to live. Little did I know, reality had some differences, but I still love it in Cape Breton. After Winston Fitzgerald, John Donald Cameron, the television show, John Allan did some touring and I was one of his two back up men and the other person was David MacIsaac. We became quite a duo and, a few years, later Hilda Chiasson made it into a trio. When the 1982 recording (Master Cape Breton Fiddler) came out, we became introduced as a kind of Cape Breton fixture, putting a new slant on things. That record seemed to have a hell of an impact with a lot of the players that were just starting out then: Dougie and Howie MacDonald and their cousin Brian, and other people like Allie Bennett. What seemed to catch their ear, according to what they’ve told me, were the arrangements: how in unison the accompaniment was. Our music seemed like a fresh idea different to anything that had been done before that. At some point I would love to take the time to put another recording of that same kind together and take it all another step further. But maybe that’ll happen, maybe it won’t: it costs a lot of money to do a big production like that.

I think it was basically in the '71-'73 period that the younger Cape Breton people began to get interested in fiddle music again. Certainly, the Glendale festival that ran in the 'seventies represented an awakening to a lot of people. One of the theories that I’ve heard over the years - I question whether I believe it or not, but it might have influenced some - credits the television shows with a role.  I was the young kid with the long hair amongst a bunch of older characters and so I became the one that the kids could supposedly relate to. But I don’t know how much friggin’ sense that makes. During that period when I was first up in Cape Breton the phone would ring asking me to play for the dances: those were the things that kept me alive during that period. In that time there was no such a thing as me or anybody else I knew of ever calling to look for a dance to play at, but almost overnight that changed up here. You see, fiddle playing at the dances used to be quite territorial, so that if you were talking Mabou, you expected to hear Donald Angus Beaton playing. If you were talking Glencoe, you expected to hear Buddy MacMaster. In Brook Village, you expected John Campbell and at the Knights of Columbus in Cheticamp, Arthur Muise. If you were talking about Sou’west Margaree, it was Cameron Chisholm and so on. Those arrangements didn’t change for years. I think the change eventually came because the younger people started calling trying to get an opportunity to play and, because they were calling, they began to get some of the gigs, and that caused a kind of a changeover from the older folks to the younger folks. So instead of a tradition of having, say, Donald Angus playing at a dance for the whole summer, you’ll now have to check the papers each week to know who’s playing in whatever places. As you saw more and more young people with wonderful abilities come out and put out records, I think they also began to get taken advantage of because of their age because some of the promoters realized that they could get the younger people for less money and they’d serve just about as well as a drawing card. To the young ones, this gave them a pretty good income considered as a teenage kind of thing, but some of the older players, myself included, became overlooked because the promoters could get the younger musicians to entertain an audience for half the price of what they were used to paying. Of course, I was taken advantage of in the same way when I was young, so I have been on both sides of the fence in this matter at different points.

I was the young kid with the long hair amongst a bunch of older characters and so I became the one that the kids could supposedly relate to. But I don’t know how much friggin’ sense that makes. During that period when I was first up in Cape Breton the phone would ring asking me to play for the dances: those were the things that kept me alive during that period. In that time there was no such a thing as me or anybody else I knew of ever calling to look for a dance to play at, but almost overnight that changed up here. You see, fiddle playing at the dances used to be quite territorial, so that if you were talking Mabou, you expected to hear Donald Angus Beaton playing. If you were talking Glencoe, you expected to hear Buddy MacMaster. In Brook Village, you expected John Campbell and at the Knights of Columbus in Cheticamp, Arthur Muise. If you were talking about Sou’west Margaree, it was Cameron Chisholm and so on. Those arrangements didn’t change for years. I think the change eventually came because the younger people started calling trying to get an opportunity to play and, because they were calling, they began to get some of the gigs, and that caused a kind of a changeover from the older folks to the younger folks. So instead of a tradition of having, say, Donald Angus playing at a dance for the whole summer, you’ll now have to check the papers each week to know who’s playing in whatever places. As you saw more and more young people with wonderful abilities come out and put out records, I think they also began to get taken advantage of because of their age because some of the promoters realized that they could get the younger people for less money and they’d serve just about as well as a drawing card. To the young ones, this gave them a pretty good income considered as a teenage kind of thing, but some of the older players, myself included, became overlooked because the promoters could get the younger musicians to entertain an audience for half the price of what they were used to paying. Of course, I was taken advantage of in the same way when I was young, so I have been on both sides of the fence in this matter at different points.

There’s a connection that’s made through the music and dance that I think is maybe more pleasing than any other style of playing. Having been both a step dancer and a square dancer, I know just how I felt when the fiddler played the right tune:  if it put you right in that groove, if it had the right drive and made you respond to it because it tickled and enthused you. If you ever have the opportunity to attend one of the dances at West Mabou or Glencoe, go outside where you’re out of sight and where nothing will take your attention away from what you hear. Now in that region you’ll find the best dancers who will stepdance even during the square dance part of the set. Just put your head against the wall while they’re in the midst of the jigs or the reels aspect of the dance. If things are really working dead on, you’ll hear this amazing connection between the fiddler and the dancers - it’ll sound like it’s just one thing happening - that one person is creating it all: the dance, the music, the atmosphere, all of it. There’s a wicked chemistry in dance playing that’s like nothing else that I’ve experienced and I don’t think there’s anything finer than encountering that kind of communication back and forth. I mean, I do love playing for people that will sit down and listen in a concert and I thrive off that kind of energy as well, but it’s really special when you’ve got all the people answering you in their dancing and you can hear their enthusiasm coming back at you: letting you know it’s worth it; letting you know that your music is tickling their funny bone or good spot.

if it put you right in that groove, if it had the right drive and made you respond to it because it tickled and enthused you. If you ever have the opportunity to attend one of the dances at West Mabou or Glencoe, go outside where you’re out of sight and where nothing will take your attention away from what you hear. Now in that region you’ll find the best dancers who will stepdance even during the square dance part of the set. Just put your head against the wall while they’re in the midst of the jigs or the reels aspect of the dance. If things are really working dead on, you’ll hear this amazing connection between the fiddler and the dancers - it’ll sound like it’s just one thing happening - that one person is creating it all: the dance, the music, the atmosphere, all of it. There’s a wicked chemistry in dance playing that’s like nothing else that I’ve experienced and I don’t think there’s anything finer than encountering that kind of communication back and forth. I mean, I do love playing for people that will sit down and listen in a concert and I thrive off that kind of energy as well, but it’s really special when you’ve got all the people answering you in their dancing and you can hear their enthusiasm coming back at you: letting you know it’s worth it; letting you know that your music is tickling their funny bone or good spot.

But, you know, there’s that other part, too: the ones that can’t keep time. And they joke about that up here: “I think that boy must be a Protestant - he can’t be a Catholic because he hasn’t got any rhythm.” There are all kinds of people in the world and you will see them all at a dance. One time Dave MacIsaac, John Morris Rankin and I were playing in Sou’west Margaree. I kept watching this one fellow up in the front set and I said to the others, “I got a feeling something funny’s gonna take place here and I don’t know why. Keep an eye on that guy there.” He was a short, skinny little guy and had a bent neck like a buzzard and his head was bigger proportion-wise to the rest of his body so it looked like they didn’t fit together very well. In the last figure of the set he was dancing with a lady from the Boston area who was very prim and proper and I imagine she must have swallowed pretty hard when he asked her to dance. I called over to Dave and John Morris, “Watch, watch, watch!” - trying to play and holler at the same time. Well, this lady had just finishing swinging with her corner partner when she turned and realized that this fellow’s pants were down around his ankles and his dirty shorts were pointing right up at her. Honest to God almighty, I’ll never forget that sight as long as I live and I can still see John Morris with his head almost hitting the keys of the piano because he was laughing so hard. So the music went into a strange lull and everybody in the hall turned around to see this fellow with the pants down around his ankles. Some of them hauled his pants back up and finally got them tied up with a piece of clothes line. He was quite upset that nobody wanted to dance with him after that. Oh yes, you can see all kinds at a dance up here.

More recently, I have been traveling to a lot of fiddle camps to teach workshops. For my first fiddle camp I got a call from Frank Ferrel that took me to Port Townsend, Washington in 1979. Now, those workshops have been a heck of a thing for me, because I never considered myself a teacher and didn’t think I had any abilities in that line, but lots of people tell me that I’m one of the teachers they most want to learn from. I find that the hardest thing to teach is style and to explain to others what my own style is, because it was created from likes and dislikes of all the different players that I have held up on the top shelf, and from the ones just under the top shelf and from the ones that eventually fell off the shelf and so on. And, as I said, playing for dances is part and parcel of what our music is about. So I didn’t know how I could communicate any of that very well. But I’ve observed as much as I could of other teachers at work, trying to hone whatever craft I’ve got so far as being a teacher is concerned. I think the biggest help to me was observing other teachers that weren’t getting their points across and recognizing what was needed. I think that patience is the greatest skill you need, just like my dad had, and a little bit of method.

In recent years there has developed a considerably better understanding for what Cape Breton music is in the outside world, better than I would have ever expected. Coming here to Cape Breton even just once will cause people to go home with a different view and understanding of our music. I’ve known people who come here with the idea in their mind that everything Natalie plays is Cape Breton or that everything Ashley plays is Cape Breton, but then they’ll go to a house party session with just two or three fiddlers and an accompanist and change their old ideas about everything. Sure, you’ll have the odd one that isn’t satisfied with what they hear and is upset not to hear the old Celtic guitar players from the 1700s with their Telecasters, but they’re really the exception. For the people who like what they experience in one of our little house parties, some of them might enjoy this type of recording that I’ve just done with Dougie over some of the big production stuff.

And I guess I must have been at this longer than I realize. About ten years ago somebody said to me, “Jerry, I expected you’d be a little beat up old man, because I’ve been listening to your music for about fifty years.” Well, I’m forty-eight now and this was ten years ago.

In these fiddle camps people come from all over for the pleasure of being in a musical group with somebody else that’s at the same skill level and for the kinds of friendships that get created in that kind of atmosphere. Sometimes they’re looking for something in this kind of music that fills a void or answers a question in a way that’s different from what they experience in their everyday 24/7 lives. And I try to answer all of their questions, although whether they are answers that they like or not is another question. But in anything I do, I try to explain that this is an Irish tune; that this is a French tune and so forth, so that’s there’s no misconception about what I’m offering. So if I say, “That was an Irish tune, played in the Cape Breton style”, I hope that they’ll understand that it is not full of the Irish rolls or embellishments but that there are more bow cuts in it than in the Irish style. Through discussions like that I try to define the differences that the Cape Breton music offers. I always try to tell the source: where I learned the tune or where it came from if I know of that. And sometimes I’ll even tell them a story about my dad and all of the other people that I’ve talked about here.

Jerry Holland

Bill Nowlin and I had recorded Jerry’s first record for Rounder back in 1976, when Bill and I were both young and Jerry was even younger. A few years ago we were considering reissuing that record which, although it does not wholly reflect Jerry’s mature style, is still wonderful and contains some of Jerry’s most delightful early compositions (including Mark Wilson’s Jig, I might add). As of 2002, I had not seen Jerry in many years, although we had talked occasionally on the phone, so Doug MacPhee and I drove over to meet him and Roberta and Gillian Head at Paul Cranford’s place north of Englishtown. We talked about reissuing the old disc, but, as I listened to Doug and Jerry play for fun during the breaks, I said to myself, “Gee, we should really make this beautiful sound available to interested listeners, for playing with Doug truly brings forth the astonishing skill and delicacy that Jerry has developed in his playing over the years. Perhaps we should wait on reissuing the old LP and instead concentrate upon getting some of this wonderful music released first.” So enchanted was I with the proceedings that I tarried too long and almost missed my plane in Halifax the next morning. At my request, Jerry and Doug played a few of my favorites from the old record and it was fun to observe how Jerry’s playing has evolved over the years. And so we have included some of those numbers here as well. I might add that the LP is currently being prepared for later reissue in this same Rounder Archive format.

Bill Nowlin and I had recorded Jerry’s first record for Rounder back in 1976, when Bill and I were both young and Jerry was even younger. A few years ago we were considering reissuing that record which, although it does not wholly reflect Jerry’s mature style, is still wonderful and contains some of Jerry’s most delightful early compositions (including Mark Wilson’s Jig, I might add). As of 2002, I had not seen Jerry in many years, although we had talked occasionally on the phone, so Doug MacPhee and I drove over to meet him and Roberta and Gillian Head at Paul Cranford’s place north of Englishtown. We talked about reissuing the old disc, but, as I listened to Doug and Jerry play for fun during the breaks, I said to myself, “Gee, we should really make this beautiful sound available to interested listeners, for playing with Doug truly brings forth the astonishing skill and delicacy that Jerry has developed in his playing over the years. Perhaps we should wait on reissuing the old LP and instead concentrate upon getting some of this wonderful music released first.” So enchanted was I with the proceedings that I tarried too long and almost missed my plane in Halifax the next morning. At my request, Jerry and Doug played a few of my favorites from the old record and it was fun to observe how Jerry’s playing has evolved over the years. And so we have included some of those numbers here as well. I might add that the LP is currently being prepared for later reissue in this same Rounder Archive format.

But getting this project to happen was another matter, as Jerry pursues the most hectic schedule of personal appearances imaginable, flying (or driving!) to widely scattered appearances everywhere, and I am able to take a week off from work only occasionally. However, we did manage to squeeze in a few days in 2003, working in hospitable environs of Roberta Head’s parlor. The results are neither tightly scripted nor carefully rehearsed, but wasn’t that our original intention? - to simply get a bit of the beautiful music I heard at Paul’s captured on CD? Jerry, meanwhile, is contemplating a number of exciting further recordings and let us hope that he will get them completed soon. As for Doug, I’m attempting to persuade him to execute a new solo recording, so I hope to offer more news on that score as well. Both artists will also appear on volume four on The Traditional Fiddle Music of Cape Breton series that Morgan MacQuarrie and I are compiling for Rounder.

I might mention that most of Jerry’s older projects are still in print (including the two wonderful tune books co-authored with Paul Cranford, which contain many of the tunes heard here) and are available either through Jerry’s own website (www.jerryholland.com) or from Paul’s (www.cranfordpub.com, which represents the best single source for Cape Breton music generally). For news of our own little stream of Cape Breton and other traditional music offerings in the NAT series, please visit www.rounder.com/rounder/nat

Mark Wilson

2. Mary Claire (Jerry Holland, SOCAN), Clear the Track, Napoleon Hornpipe, Tom Marsh (Vincent MacGillivray) - hornpipes.

![]() 3. Mrs MacDouwal Grant - slow strathspey, Dr Keith Aberdeen (J Scott Skinner), Highlands of Banffshire (Simon Fraser) - strathspeys; Mrs Gordon of Knockspoch (William Marshall), Reel du Vétérinaire (sound clip), Dan Galbey’s - reels.

3. Mrs MacDouwal Grant - slow strathspey, Dr Keith Aberdeen (J Scott Skinner), Highlands of Banffshire (Simon Fraser) - strathspeys; Mrs Gordon of Knockspoch (William Marshall), Reel du Vétérinaire (sound clip), Dan Galbey’s - reels.

4. Mrs Norman MacKeigan (Dan R MacDonald, SOCAN), Tom Steele, The Boys of the Loch - reels.

5. Pretty Maggie Morrissey, Dunphy’s Hornpipe - Irish hornpipes; Sally Gardens, King of the Clans - Irish reels.

6. All My Friends (Jerry Holland, SOCAN), Joey Beaton’s Reel (Jerry Holland, SOCAN), Golden Locks (Simon Fraser) - reels.

7. The Pattern Day, The Panelmine Jig (John Campbell), The Wedding Jig (Dan R MacDonald, SOCAN), Teviot Bridge, The Stool of Repentance - jigs.

![]() 8. Tom Dey (sound clip) (J Scott Skinner), Old Style Strathspey as played by Mary MacDonald, Sandy Cameron (J Scott Skinner) - strathspeys; The Marchioness of Tullybardine - reel.

8. Tom Dey (sound clip) (J Scott Skinner), Old Style Strathspey as played by Mary MacDonald, Sandy Cameron (J Scott Skinner) - strathspeys; The Marchioness of Tullybardine - reel.

9. Niel Gow’s Lamentation for James Moray of Abercairny - slow air; Mary Grey - strathspey; Dave Normaway MacDonald’s Wedding (Jerry Holland, SOCAN), Arthur Muise (Jerry Holland, SOCAN) - reels.

10. The Waking of the Fauld, The Devil in the Kitchen (William Ross) - strathspeys; The Grey Old Lady of Raasay, Miss Charlotte Alston Stewart’s, Sandy Cameron’s, Put Me in the Big Chest - reels.

![]() 11. Pipe Major Donald MacLean of Lewis (sound clip) (Donald MacLeod); I Won’t Do the Work - jigs.

11. Pipe Major Donald MacLean of Lewis (sound clip) (Donald MacLeod); I Won’t Do the Work - jigs.

12. Mrs Crawford (Robert Petrie), O’er the Moor Among the Heather - marching airs; Sir Archibald Dunbar, Kiss the Lass You Love Best - strathspeys; The Darling of the Uist Lasses, Sir David Davidson of Cantry (Joseph Lowe), Celtic Ceilidh (Dan R MacDonald, SOCAN) - reels.

13. Kathleen’s Jig (Dan Hughie MacEachern, SOCAN), The Royal Circus, Miss Carmichael (William Shepherd) - jigs.

| Introduction | Joe Peter MacLean | Alex Francis MacKay |

14.10.05

Article MT170

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |