Article MT269

Note: place cursor on red asterisks for footnotes.

Place cursor on graphics for citation and further information.

Sound clips are shown by the name of the tune being in underlined bold italic red text. Click the name and your installed MP3 player will start.

Walter Jeary

North Norfolk dulcimer player, singer and step dancer

Walter Jeary was in many ways a typical traditional rural musician, a highly-regarded entertainer who learnt his instrument in his community and was later regarded as something of a virtuoso. He also sang comic songs and was a very accomplished step dancer. True to this, music was never a profession; he worked as a farm manager for most of his life, as well as being active as a musician in the areas of north Norfolk in which he lived at various times of his life.

Walter Jeary was in many ways a typical traditional rural musician, a highly-regarded entertainer who learnt his instrument in his community and was later regarded as something of a virtuoso. He also sang comic songs and was a very accomplished step dancer. True to this, music was never a profession; he worked as a farm manager for most of his life, as well as being active as a musician in the areas of north Norfolk in which he lived at various times of his life.

Walter was born in 1901 in Bodham. His two brothers, Ernest (b.1903) and Herbert (b.1905), were also very accomplished step dancers. All three had nicknames: Walter was 'Slim,' Ernest was 'Dough' and Herbert was 'Shamrock'. This was common enough in the early Twentieth Century and Walter's daughter Madeline Grice 1 recalls that, "They called him Uncle Dough. I think he was probably a baker at one point." Walter himself had this to say about why he was called 'Slim': "I was a thatcher on a farm; I won first prize, Lynn Show. Thatchin'. I was up and down the ladder and back again before old chap got started. They used to call me 'Slim'; they didn't call me that for nothing, nor football either! Always used both feet alright!"

1 recalls that, "They called him Uncle Dough. I think he was probably a baker at one point." Walter himself had this to say about why he was called 'Slim': "I was a thatcher on a farm; I won first prize, Lynn Show. Thatchin'. I was up and down the ladder and back again before old chap got started. They used to call me 'Slim'; they didn't call me that for nothing, nor football either! Always used both feet alright!" 2 Nobody seems to know why Herbert was 'Shamrock'.

2 Nobody seems to know why Herbert was 'Shamrock'.

In 1918 the family moved to Gunthorpe where the boys' father, also Walter, took over the running of The Cross Keys pub. Walter Jeary Snr was something of a character and his son Walter recalled, "My father kept the pub for thirty three years. We had some good times in that." Walter's son Jimmy 3 remembers his grandfather: "He was a rum bloke, he was, old Walter Jeary. I see him now, little old brown trilby hat on. One night; I was only a young lad then, very young fella, very young indeed really; there was a lot of Air Force blokes in there, and he said, "Time," and they said, "We aren't a-goin'." He said, "Well, perhaps this'll help you," and he fired a 12-bore gun across the pub! He said, "Next one, that won't go out in the corner, that'll go into you lot."

3 remembers his grandfather: "He was a rum bloke, he was, old Walter Jeary. I see him now, little old brown trilby hat on. One night; I was only a young lad then, very young fella, very young indeed really; there was a lot of Air Force blokes in there, and he said, "Time," and they said, "We aren't a-goin'." He said, "Well, perhaps this'll help you," and he fired a 12-bore gun across the pub! He said, "Next one, that won't go out in the corner, that'll go into you lot."

There was much music in the pub and it was in this environment that Walter Jeary first started performing. His father was a step dancer and would play the concertina for his sons to practice stepping. Of this music in the pub, Madeline Grice recalls, "But during the war, The Cross Keys; they used to have all the Air Force from Langham there. And they had a piano in the lounge and all the old boys used to step dance, and it was wonderful. Dad and his brothers, Herbert and Dough, they all used to step dance, and dad used to yodel as well.

"He started playing his dulcimer in the pub grandfather ran, you see. I always remember we had one gentleman used to come in The Cross Keys; I was very young; Mr Bean, and they used to call him "Stringbean." He always had a pint with a poker in it. Mulled. And grandad used to keep the poker in the fire and have to mull Sid Bean's pint.

"He started playing his dulcimer in the pub grandfather ran, you see. I always remember we had one gentleman used to come in The Cross Keys; I was very young; Mr Bean, and they used to call him "Stringbean." He always had a pint with a poker in it. Mulled. And grandad used to keep the poker in the fire and have to mull Sid Bean's pint.

"They used to go out dart-matching even then and grandad would never buy a pint in his own pub, but he'd treat everybody when they went. He said, "'Cause if I buy 'em in my pub, I'm paying for it twice." And our father, the dear Walter, he was exactly the same. If he lost at darts and the man opposite him was drinking pints, he'd ask him what he's having a half of! He was quite a character, wasn't he?

"Oh yes, he used to go to all the pubs and we used to go with him. We went to dart matches. The old dulcimer used to come in the place and dad'd get the dulcimer out. "Give us a tune, Wally!" Down in The Cross Keys, when they had Uncle Dough and Uncle Shammy and dad used to do it together, the three of them: they used to all step dance and even the old grandads used to do it."

Walter Jeary was taught to play the dulcimer by a blind man in Bodham, when he lived in that village, who Jimmy Jeary recalls might have been called Burgess 4. After that he seems to have played by himself; his father had a dulcimer but nobody can remember him ever playing it.

4. After that he seems to have played by himself; his father had a dulcimer but nobody can remember him ever playing it.

He certainly was a very accomplished player. He was visited in the mid 1970s by David Kettlewell, researching his thesis on Dulcimers in the British Isles since 1800 5, who described his style thus: "(he) has a very personal style, where the hammers keep up a constant crotchet rhythm whatever the rhythm of the original tune." Kettlewell also maintains that "Walter Jeary played two hours a day for ten years."

5, who described his style thus: "(he) has a very personal style, where the hammers keep up a constant crotchet rhythm whatever the rhythm of the original tune." Kettlewell also maintains that "Walter Jeary played two hours a day for ten years." 6

6

Madeline Grice remembers that "He couldn't read music. But he'd play it blindfold, what was a bet he used to take on, and they'd put money in the hat in the pub. They used to blindfold him and tell him to play something," and Jimmy Jeary recalls, "He used to cover it (the dulcimer) up, you know. He could still play it. Put a cloth over the top. He never did make a mistake."

These tricks seem to have been successful, but Kettlewell also mentions, "One couple in The Ship, Cromer, remembered Walter Jeary playing the dulcimer behind his back; however he himself was not sure if he had done so or not, and when he tried it at home it certainly looked fairly impossible."

Like many local players, Walter made his own beaters. Jimmy Jeary: "I've seen him indoors nights, making his sticks," and another daughter Rosina Farrow remembers, "I can see Dad now. He used to use wool." David Kettlewell remarks, "The hammers or beaters are home-made from cane (Walter Jeary of Northrepps, near Cromer, Norfolk, recommends crab-pot cane) looped over at the playing end and wound with wool."

Like many local players, Walter made his own beaters. Jimmy Jeary: "I've seen him indoors nights, making his sticks," and another daughter Rosina Farrow remembers, "I can see Dad now. He used to use wool." David Kettlewell remarks, "The hammers or beaters are home-made from cane (Walter Jeary of Northrepps, near Cromer, Norfolk, recommends crab-pot cane) looped over at the playing end and wound with wool."

The Jeary family were in Gunthorpe for many years and Madeline Grice remembers that "the last time I saw the boys tap dancing together was granny and grandad's golden wedding at The Cross Keys. During the war. They had their fiftieth, their golden wedding there." She also recalls that "Dad had a butcher's shop attached to the pub, in Gunthorpe, and he used to kill his own pigs." Unfortunately this wasn't to last, as the agricultural depression of the 1930s meant that he couldn't keep the business going and "we moved to Docking, in west Norfolk, on the old farm; on the Sunderlands' farm, which was taken over for a satellite airfield. That was right opposite Bircham Newton and dad used to play the dulcimer there in the pub, down at Stanhoe, for the aircrew. The Stanhoe Hero." 7

7

One pub in Docking in which Walter played was The King William IV, and his playing seems to have augmented the family income to some extent. Jimmy Jeary: "When we were small we lived at Docking. We used to live about half a mile off Docking, and my father used to carry his dulcimer on the crossbar of his bike, to The King William at Docking, and he'd play there on a Christmas Eve. He'd bring enough pennies and that home to see us right through Christmas. If he got a bit of silver in with that, he was pleased!" Likewise Madeline Grice: "I remember as kids, mum and dad used to count all the money, Sunday mornings. 'Cause they used to go round with a hat, and he'd always played his dulcimer."

Walter Jeary had a huge family, as Jimmy recalls, "I know Sunday nights sometime, years ago, we'd all get round the table; he'd be a-playing, we'd all be a-singing. There were seven of us, you see. Five sisters and brother. My brother went in the army." When Walter's wife died, he married again, greatly enlarging the family, as Jimmy's wife Peggy explains: " 'Cause when he married you all lived with the oldest sister. Moved out, 'cause the new wife's family moved in, sort of thing. She had nine and there were seven of them. It was a little bit complicated."

Madeline Grice remembers the music making at home on Sunday nights: "As a kid, we knew nothing else, did we? Sunday nights was the front room. And we were allowed in there, and we used to pull the curtains, and dad'd play the dulcimer and we used to have to walk out and do our acts for him. Well, it was always music in our house when we were kids. When dad got his dulcimer out and started playing The Bluebells of Scotland us kids knew what we were in for. Rosie had to sing The Poor Crippled Boy. And he used to have a thing he used to play called the Can You Stand It? Jig. He used to go up and down the keys and us kids used to have to jump up and down! I don't know where this song came from even, but he used to say, "Now I'll play the Can You Stand It? Jig." So where he got it; whether it was a real Norfolk jig, or whatever it was, I don't know."

Despite this encouragement to participate in home entertainment, Walter does not seem to have had the desire to pass on dulcimer-playing to any of his children. Jimmy: "No, old chap wouldn't hardly ever let you touch it, you know. He wouldn't let anyone touch that."

Jimmy Jeary is the only one of the children who ever accompanied his father playing outside the house, and this happened particularly once the family had moved to Northrepps. Walter became farm manager for an old school friend, Maurice Grief, who owned Cherry Ridge in Northrepps. Once in the village, both Walter and Maurice Grief also played regularly for the village football team. At some point around this time Walter had a nasty accident with a horse on the farm, as Jimmy recalls: "That kicked him. Had one horse as a trace horse, they call it, in a cart, and a fly stung it, and old horse kicked out. 'Cause they always kick backwards, don't they? Kicked him backwards in the face. Old man was tough!" The incident left Walter blind in one eye and partially deaf. This in no way seems to have impaired his music making however.

Jimmy would accompany his father on the bones, particularly in Northrepps Foundry Arms. This was held by Mr and Mrs Short at this time

Jimmy would accompany his father on the bones, particularly in Northrepps Foundry Arms. This was held by Mr and Mrs Short at this time 8 and seems to have been a lively pub for music, as Jimmy remembers: "it'd be about 10 o'clock night time, or half past nine. They shut at half past ten then. "Go and get the old music, Wally!"

8 and seems to have been a lively pub for music, as Jimmy remembers: "it'd be about 10 o'clock night time, or half past nine. They shut at half past ten then. "Go and get the old music, Wally!" 9 And he's just across the road, and we used to get the old dulcimer and cor, we'd have a tune-up!"

9 And he's just across the road, and we used to get the old dulcimer and cor, we'd have a tune-up!"

Jimmy is a good bones player, well able to play with both hands, and recalled one incident in the pub with a local character: "Bill Thridgett 10 used to play these (bones). We were in The Foundry Arms one night. He said, "I'll give anyone a pound who'll play these." We give him a quid (for the bet). He was a rare hand at these, for a start." In the ensuing competition, Bill Thridgett was completely shown up by Jimmy. "He didn't like it at all."

10 used to play these (bones). We were in The Foundry Arms one night. He said, "I'll give anyone a pound who'll play these." We give him a quid (for the bet). He was a rare hand at these, for a start." In the ensuing competition, Bill Thridgett was completely shown up by Jimmy. "He didn't like it at all."

Madeline Grice remembers, "We went to Northrepps and dad used to play the dulcimer in the old Foundry. I had my wedding reception there and father played the dulcimer. And sometimes we had to persuade him, especially when I used to come home for weekends and we'd go in The Foundry Arms. And sometimes I'd say, "Come on Dad, play." But especially if you'd brought friends who didn't know him, he'd keep on and he'd block his ears," but eventually after some persuading, "he'd play all night then. The day the war ended, we got in The Foundry Arms and dad played the dulcimer then. I remember we all got called in off the field, "The war's over, the war's over!" 'Cause we were working on the farm. And we all came down and we all went in The Foundry Arms and dad played the dulcimer. Vera Lynns!"

Very often it was just Walter and Jimmy playing in the pub, but sometimes others would join in. Jimmy remembers, "Ambrose Reynolds. He'd play an accordion. Kenny Hunt used to play (the banjo). They'd have a rare band here some Friday nights. That we did. We'd have a rare old sing-song."

Elsewhere, Walter and Jimmy played in The Vernon Arms in neighbouring Southrepps. This was another lively pub for music, run by Ben Baxter, a singer with a large repertoire. His brother Harry played the fiddle to accompany step dancing. 11 "I remember Harry. 'Cause he made a dulcimer. My father used to go and play it for him. They used to step dance a lot." Another excursion would sometimes be to Cromer, particularly to The Albion, frequented by the fishermen, many of whom were step dancers. "I've been here and they've got on a tray. Saturday nights. And I've seen them step dance on a tray, and one get off, one get on." Jimmy also remembers, "He played in Briston. In The Horseshoes, I reckon. Wherever Dick

11 "I remember Harry. 'Cause he made a dulcimer. My father used to go and play it for him. They used to step dance a lot." Another excursion would sometimes be to Cromer, particularly to The Albion, frequented by the fishermen, many of whom were step dancers. "I've been here and they've got on a tray. Saturday nights. And I've seen them step dance on a tray, and one get off, one get on." Jimmy also remembers, "He played in Briston. In The Horseshoes, I reckon. Wherever Dick 12 was. Used to play at Thornage Black Boys."

12 was. Used to play at Thornage Black Boys."

Jimmy actually bought a dulcimer for his father: "He had two. I bought one, the big one what he finished up with. I bought it off a Letheridge. Used to have a shop. Dickey dealers, they used to call them. Used to have a shop where the old Eastern Daily Press used to be, years ago, right on that corner off Church Street. 13 That was in the window. I was returning along of old chap one day. I say, "Look there Wally. Oh, that's a nice 'un, in't it? I'll go and get that for you." Do,

13 That was in the window. I was returning along of old chap one day. I say, "Look there Wally. Oh, that's a nice 'un, in't it? I'll go and get that for you." Do, 14 I give him three quid for that. That was donkey's years ago. I was fifteen. I went and bought that for him for three quid."

14 I give him three quid for that. That was donkey's years ago. I was fifteen. I went and bought that for him for three quid."

Madeline remembers that her father's dulcimer "didn't even have a strut (stand) on it. He used to have to put something under it to keep it; it was a pint pot when he was in the pubs. But when we were at home it used to be a tin or a cup or something underneath it, to keep it slanted."

Walter's playing was done in pubs and also sometimes for weddings, but never for country dances in village halls or similar venues. When asked by David Kettlewell in the mid-1970s about this, Walter and his second wife Lena considered that dances were the province of quite large bands, rather than village musicians. However, in conversation with Anne-Marie Hulme and Peter Clifton in 1977 he diddles Up the Middle and Down the Sides and sings/diddles Heel and Toe Polka and Oh Joe, the Boat is Going Over, as well as diddling a schottische tune, 15 although his comment that "I knew the tune because I heard it dozens of times" might suggest that he didn't actually play it himself very often, particularly as he associated it with accordion playing.

15 although his comment that "I knew the tune because I heard it dozens of times" might suggest that he didn't actually play it himself very often, particularly as he associated it with accordion playing.

With prompting from Anne-Marie Hulme and Peter Clifton, Walter and Lena do try to describe the figures of a dance performed in the pub, which Walter called the Scotch Reel: "There'd be four that side, or however many there would. Sometimes there'd be ten on 'em! Five each side. Well, they'd go that side and you'd go this. And reel off…You'd start from that side, and start to come round, when these lot start to come this way… And then you start in her place, still a-settin'… The old chap what's playing the music say, "Reel off!" and this side'd go down that side. Off they go again… That used to be a treat to watch 'em on a Saturday night."

Another dance mentioned by Walter was The Keel Row: "And then they'd do The Keel Row. That's like the parson once said; he said, "We're now going to do The Keel Row," he said, "And I hope everybody," he said, "will sing the correct version and not the army version; The monkey cocked his tail up!" 'Cause that's what they used to sing in the army, y'know! Well, you've seen 'em do it all with swords, haven't you? Well, of course, they didn't use to have swords; they had sticks. Do, their corns wouldn't look too good!"

Certainly the pub dancing was lively: "They'd go three one way, and three another. I never did do that much. They used to do it lovely, and all; some of them old gents. They'd go round; they used to dance with their hats on, them old blokes. Especially after had a pint or two. And the pipes in their mouths, very often too!"

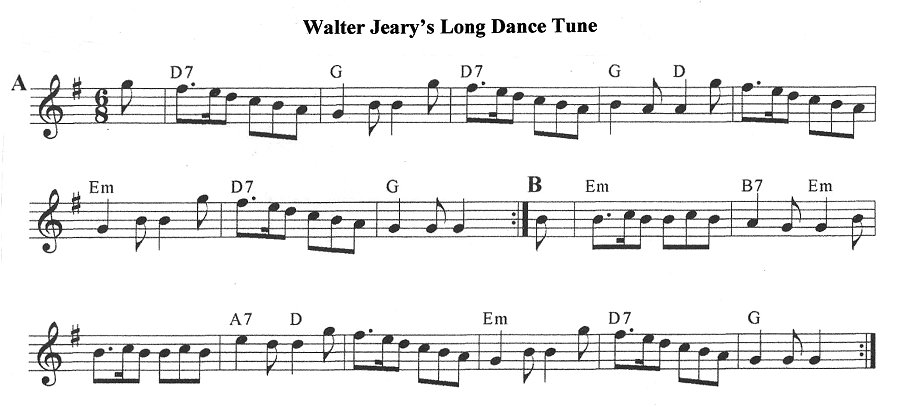

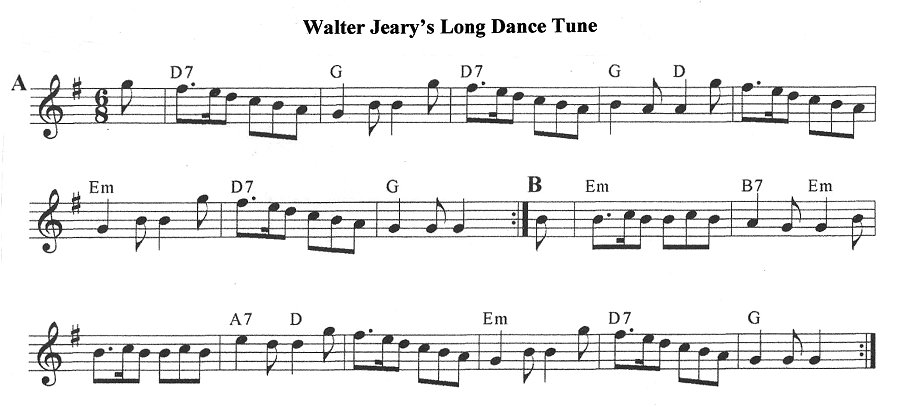

Walter had a tune for the Long Dance, which he played to David Kettlewell, and which was also noted down by Norris Winstone of Norwich. 16 This tune seems unique to Walter, although it has similarities with Garyowen in places. To what extent Walter played for the Long Dance is unknown; it is not a dance which could have taken place in a pub, unless the room was of a considerable size.

16 This tune seems unique to Walter, although it has similarities with Garyowen in places. To what extent Walter played for the Long Dance is unknown; it is not a dance which could have taken place in a pub, unless the room was of a considerable size.

As well as playing the dulcimer, Walter Jeary was also a regular singer, with a particular penchant for comic songs, as Madeline Grice remarks:" The one I remember most was Henery the Eighth. I can always hear dad singing that: I'm Henery the Eighth, I am, I am. A Long Way to Tipperary, that was one of his favourites. Yeah, he loved that one. What would he use to sing it? A long, long time to tip a Jeary; takes a long, long way to tip a Jeary. 'Cause during the war lots of nasty kids used to call us "Jerry." Every nice girl should love a sailor, something like that. I call for Kate and Jane, and he'd love to see again; Ship Ahoy! Now's the Hour. Oh yeah, that was the last one he used to play, when the new ones came. When Nanny Short used to ring the bell, father would play Now's the Hour.

Walter very often accompanied himself on the dulcimer with favourites such as Covered Wagon and Farmer's Boy. A particular favourite of his was Hold Your Row, a local version of this popular comic song:

I -too-ra-li, oo-ra-li, oo-ra-li, a,

I went forth to meet her at Southrepps one day.

At Southrepps the land 17 looks big every day,

17 looks big every day,

I-too-ra-li, oo-ra-li, oo-ra-li, a.

I called on my sweetheart, her name was Miss Brown.

She was having a bath and she couldn't come down.

I said, "Slip on something, dear, come half a tick."

She slipped on the soap and come down oh so quick.

Hold your row, hold your row,

They're all idle fellows who follow the plough.

A nasty black eye had my brother Jim.

He said his wife threw a tomato at him.

"Tomatoes don't hurt," I said with a grin.

He said, "This one did, it come by in the tin!"

Hold your row…

I dreamt that I'd died and to heaven did go.

"Where do you come from?" they wanted to know.

I told them from Northrepps; St Peter did stare.

He said, "Hurry you up, you're the first one from there."

Hold your row…

Now put four old maidens round four cups of tea,

They'll talk of more scandal than you ever did see.

But put four good men round a barrel of beer,

They'll talk of more work than they do in a year.

Hold your row…

"Now what do you think?" said my young brother Joe.

"My hen's laid a duck's egg." I said "Is that so?"

"There's nothing so bonny in that what you're told,

For an aunt of mine once laid a foundation stone."

Hold your row…

Walter continued to step dance, following on from the days when he did so with his brothers and father in Gunthorpe Cross Keys, as Madeline Grice recalls: "I've seen him do it on the table in The Stanhoe Hero." Peter Clifton and Anne-Marie Hulme visited Walter and Shamrock in 1977 to collect information about their stepping style. They had identified three distinct styles in north Norfolk: a traditional local style, a traveller style and a form of Lancashire stepping performed by the Davies family of Cromer. 18 They considered Dick Hewitt

18 They considered Dick Hewitt 19 of Briston and the Jeary brothers to be exponents of the traditional 'Norfolk Stepping' style:

19 of Briston and the Jeary brothers to be exponents of the traditional 'Norfolk Stepping' style:

"Two dancers unfortunately no longer active are the brothers Shamrock and Walter Jeary, now in their late seventies. Their father kept the pub at Gunthorpe for thirty-eight years (sic). Each evening after tea the boys were made to practice their dancing accompanied by their father's concertina."

"The brothers both speak of step dancing competitions before the First World War arranged between pubs in such places as Melton Constable, Fakenham and Briston. The winner was given free beer or some other small prize. The dancer stepped on a 9'' square tile and was disqualified if his feet strayed over the edge. Two or more older dancers would judge the contest and their decision often resulted in fisticuffs outside! The dancers mostly wore hobnailed boots though it was known for some to wear clogs. Clogs were easily obtainable at the shoemakers and were common working wear."

"Wally first entered these contests aged eighteen in about 1920, but he remembers them being held earlier from about 1910. Wally has been described to us by others as a champion. His neat light style involving little movement was ideally suited to these contests and he modestly admits that he never came second. At seventy-six he proved himself to be a first-class stepper when, in his carpet slippers, he diddled and stepped for us in his kitchen. At seventy-three Shamrock danced in The Green Man for us, following Dick Hewitt four times before sitting down. At his home in Peterborough he taught us the single and the double, dancing on the back of an old photograph."

On the recordings Peter Clifton and Anne-Marie Hulme made of Walter he does indeed step dance very well whilst diddling Yarmouth Hornpipe and Why did I kiss that girl? and demonstrates various steps. Jimmy Jeary remarks that "He put treble step in fast," and Walter himself comments, "I always got a first! I could do all them, but I ceased. As you get older, you get out of practice."

As he got older, Walter moved with Lena to a bungalow in Croft Lane, Southrepps. He is very fondly remembered by his children, as Madeline Grice attests: "He had the most fantastic sense of humour. He always used to tell us girls, "Never darn your stockings. A hole is a thing of the moment, and a darn is a sign of poverty." When we were kids we used to think he could see what we did with his glass eye."

Unfortunately, Walter Jeary was not widely recorded. David Kettlewell made some recordings whilst researching his thesis, mainly fragments of tunes interspersed with talking. Russell Wortley recorded him in 1958 and these tracks do give a clear insight into his style: rhythmic country dance tunes such as the Sheringham Breakdown, the Sailor's Hornpipe and the Yarmouth Hornpipe (all step dance favourites), plus the Cock of the North and the Heel and Toe Polka. Also recorded were favourite songs played on the dulcimer, often while he sang or hummed along: Covered Wagon, Old Faithful and the Farmer's Boy. 20

20

Thanks to John Howson for the use of the above recordings from the double cassette, I Thought I Was The Only One: Dulcimer Players From England (Veteran VTVS07/08). It is currently unavailable but is due to be rereleased on CD in the not-too-distant future.

Walter Jeary died in 1985. Madeline Grice remembers, "I know I went to see him the night before he died, and he didn't look more than sixty," and also makes the apt comment, "He was an excellent player, there's no two ways about it."

Chris Holderness - 28.1.12

Rig-a-Jig-Jig: A Norfolk Music History Project

Notes:

1. Madeline Grice and Rosina Farrow interviewed by Chris Holderness in Sheringham on 01.13.07.

2. Recorded by Peter Clifton and Anne-Marie Hulme in 1977. Thanks to Phil Heath Coleman for providing the recording and to Paul Marsh for digitising it in March, 2008.

3. Jimmy and Peggy Jeary interviewed by Chris Holderness in Cromer on 25.02.07.

4. I have not been able to find out more about this blind player, but there was a blind dulcimer player living in Briston in the early Twentieth Century called Herbert Burgess. He may have been the same man. See article MT 249: Briston and Melton Constable: traditional music making in two neighbouring Norfolk villages.

5. David Kettlewell's thesis Dulcimers in the British Isles since 1800 can be seen online at: www.new-renaissance.eenet.ee/dulcimer

6. From David Kettlewell's article 'That's what I calls a striking sound' - the Dulcimer in East Anglia in two parts in English Dance and Song, 1974. The photograph of Walter Jeary comes from the same source.

7. The full name of the pub is The Norfolk Hero, also known as The Nelson. (Source: www.norfolkpubs.co.uk from where also comes the photograph of Gunthorpe Cross Keys).

8. John Short is listed as having the pub from 28.02.38 and Mrs Elsie Short from 25.08.51 until 21.09.53. Maybe 'Nanny' Short carried on running the pub after her husband died. (Source: as 7 above).

9. 'Music' here refers to his instrument; this was very common in East Anglia. It is interesting that Walter Jeary waited until he was asked, before going home to get his instrument. The same situation happened with Billy Lown of Cley and his melodeon. See article MT 198: Billy Lown and Philip Hamond: two North Norfolk singers.

10. Bill Thridgett was a local character who used to play regularly with Percy Brown. See article MT 211: Percy Brown: Aylsham Melodeon Player.

11. See article MT221: Southrepps: Singing and Step Dancing in a north Norfolk Village for more information about music in The Vernon Arms.

12. For more information about step dancer Dick Hewitt see article MT245: Dick Hewitt: a True Norfolk Man.

13. The street name is not clear on the recording; I'm assuming it to be Church Street in Cromer.

14. 'Do' - a Norfolk dialect word, normally meaning 'otherwise', but meaning 'and so' in this context.

15. The Moldavian Schottische. Basically the same tune as Beatrice Hill's Three-Hand Reel. Thanks to Phil Heath-Coleman for the 'proper' title.

16. Thanks to Alan Helsdon for providing a transcription of Walter Jeary's Long Dance tune, as noted down by Norris Winstone.

17. This word is indistinct on the recording, so I'm making a guess!

18. From 'Solo step dancing within living memory in North Norfolk' in Traditional Dance - volume 1, 28.03.81

19. See MT245 as above for more information.

20. See discography below for details of available recordings.

Discography:

I Thought I Was The Only One: Dulcimer Players From England (Veteran VTVS07/08) - this recording contains the eight tracks recorded by Russell Wortley mentioned in the penultimate paragraph of the article.

Article MT269

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 28.1.12

Walter Jeary was in many ways a typical traditional rural musician, a highly-regarded entertainer who learnt his instrument in his community and was later regarded as something of a virtuoso. He also sang comic songs and was a very accomplished step dancer. True to this, music was never a profession; he worked as a farm manager for most of his life, as well as being active as a musician in the areas of north Norfolk in which he lived at various times of his life.

Walter Jeary was in many ways a typical traditional rural musician, a highly-regarded entertainer who learnt his instrument in his community and was later regarded as something of a virtuoso. He also sang comic songs and was a very accomplished step dancer. True to this, music was never a profession; he worked as a farm manager for most of his life, as well as being active as a musician in the areas of north Norfolk in which he lived at various times of his life.

"He started playing his dulcimer in the pub grandfather ran, you see. I always remember we had one gentleman used to come in The Cross Keys; I was very young; Mr Bean, and they used to call him "Stringbean." He always had a pint with a poker in it. Mulled. And grandad used to keep the poker in the fire and have to mull Sid Bean's pint.

"He started playing his dulcimer in the pub grandfather ran, you see. I always remember we had one gentleman used to come in The Cross Keys; I was very young; Mr Bean, and they used to call him "Stringbean." He always had a pint with a poker in it. Mulled. And grandad used to keep the poker in the fire and have to mull Sid Bean's pint.

Like many local players, Walter made his own beaters. Jimmy Jeary: "I've seen him indoors nights, making his sticks," and another daughter Rosina Farrow remembers, "I can see Dad now. He used to use wool." David Kettlewell remarks, "The hammers or beaters are home-made from cane (Walter Jeary of Northrepps, near Cromer, Norfolk, recommends crab-pot cane) looped over at the playing end and wound with wool."

Like many local players, Walter made his own beaters. Jimmy Jeary: "I've seen him indoors nights, making his sticks," and another daughter Rosina Farrow remembers, "I can see Dad now. He used to use wool." David Kettlewell remarks, "The hammers or beaters are home-made from cane (Walter Jeary of Northrepps, near Cromer, Norfolk, recommends crab-pot cane) looped over at the playing end and wound with wool."

Jimmy would accompany his father on the bones, particularly in Northrepps Foundry Arms. This was held by Mr and Mrs Short at this time

Jimmy would accompany his father on the bones, particularly in Northrepps Foundry Arms. This was held by Mr and Mrs Short at this time