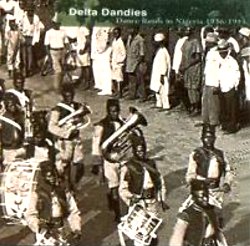

Dance Bands In Nigeria, 1936-1941

Savannahphone AFCD011

Apolo Aigbodion: Uki Khi Yomba; Jolly Orchestra: Egbe Jolly/ Gbogbo Eniyam Feran Jo Satid; Etim Henshaw: Wom Wom Sit Wom/ Nkpo Nnam Isuhoke Owo; Ibo Youth Orchestra: Enu Uwabu; Gold Coast Police Band: Rocking in Rhythm/ Elmina Blues; Godwin Scotland : Adelebo Ilu Eko; Onitsha Native Orchestra: Oje Mba/ Angelina; Lagos Mozart Orchestra: Esan Inyong Ikide/ Nne O! Ke Ndi; Mr Harry Taylor: Kini Nyana Bo Boma; SS Peters: Madam Mary; Ifon Adeko Players: Oba Imo Kawa

All those years when it seemed like hardly anybody was interested in listening to, collecting and documenting early commercial African recordings, there appears actually to have been a substantial number of enthusiasts waiting until the time was right to break cover. That time seems to have come round at last, as evidenced by the blossoming over the last few years of a whole range of websites devoted to the diverse aspects of this area of interest. Thereís sites like Savannahphone (of which more later), with its invaluable discographies of West African 78s, and Kentanza, with its label-by-label listings of East African 45s; thereís Likembe, offering regular dollops of out-of-print LPs through a filesharing blog, and Excavated Shellac, which focuses on one carefully-selected and beautifully-restored 78 at a time, and regularly features African material as part of its pan-global policy. And there are quite a few more covering similar ground, and doing excellent work, from Bolingoís extensive documentation of Congolese music on record (including such delights as a full scan of the 24-page catalogue of Esengo records from the early 1960s), to Toshiyo Endoís now longstanding, and continually growing, artist discographies.

All those years when it seemed like hardly anybody was interested in listening to, collecting and documenting early commercial African recordings, there appears actually to have been a substantial number of enthusiasts waiting until the time was right to break cover. That time seems to have come round at last, as evidenced by the blossoming over the last few years of a whole range of websites devoted to the diverse aspects of this area of interest. Thereís sites like Savannahphone (of which more later), with its invaluable discographies of West African 78s, and Kentanza, with its label-by-label listings of East African 45s; thereís Likembe, offering regular dollops of out-of-print LPs through a filesharing blog, and Excavated Shellac, which focuses on one carefully-selected and beautifully-restored 78 at a time, and regularly features African material as part of its pan-global policy. And there are quite a few more covering similar ground, and doing excellent work, from Bolingoís extensive documentation of Congolese music on record (including such delights as a full scan of the 24-page catalogue of Esengo records from the early 1960s), to Toshiyo Endoís now longstanding, and continually growing, artist discographies.

The last few years has also seen a steady, if not exactly overwhelming, stream of compilations of long-unavailable 78s on CD, after a long gap when hardly anything was appearing. Honest Jonís batch of reissues over the last few years, featuring African music recorded in the UK, has already been mentioned in these pages (see my review of Living Is Hard, HJRCD33). In 2006, a new label emerged, under the name of Savannahphone (whose website has already been mentioned, above), to release in conjunction with The British Library, the magnificent Awon Ojise Olorun: Popular Music In Yorubaland 1931-1952, Savannahphone CD AF 010, the first survey of early commercial Yoruba recordings since Rounderís Juju Roots more than two decades earlier. I wonder how many people snapped that release up (far fewer than it deserved, Iíd guess), but apparently enough to encourage Savannahphone to compile and release a companion volume, Delta Dandies, now in conjunction with Honest Jonís and with support from the Arts Council. Where Awon Ojise Olorun explored the development of three of Nigeriaís most popular styles - sakara, juju and apala - this one looks at some of the precursors of the highlife that was to proliferate in post-war West Africa, through the evidence of HMV and (mostly) Parlophone recordings in the 1930s and Ď40s.

If the subtitleís reference to 1930s dance bands conjures up orchestrated gents in neat rows of uniform suits, be assured that isnít what this album delivers. On the contrary. Its first track, by Apolo Aigbodion, features a few western stringed instruments (at a guess, a guitar, a banjolele and a mandolin), some makeshift percussion (a knife striking a bottle, maybe), a kazoo (probably improvised from comb and paper), with ensemble vocals. Itís a rough sound, but filled with exuberant energy. The Jolly Orchestraís membership included Ambrose Adekoya Campbell and Brewster Hughes, who in the post-war years became two of the most important African musicians in the UK (and are to be heard on the Honest Jonís CDs already mentioned). Perhaps we canít know for sure that they were in the lineup that made the two sides included here, but itís nice to think that they were, and certainly the duetting guitars that make up the basis of the bandís accompaniment might be showing early signs of the kind of progressive approach to fusing different influences that made The West African Rhythm Brothers and the Nigerian Union Rhythm Band the biggest highlife acts in London a decade and more later. The Hawaiian-influenced slide guitar on Egbe Jolly is an unpredictable touch, while Gbogbo Eniyan Fíeran Jo Satide is an early take on the West African standard Everybody Loves Saturday Night. Neither Campbell or Hughes seem to have recorded this song during their later Melodisc days, but it seems likely that they would have performed it often enough.

Some of the best guitar playing is to be heard on Enu Uwabu Oriri by the Ibo Youth Orchestra - fast fingerpicking on one guitar intertwining with snapping, rhythmic thumb strokes on another - great melodic and harmonic stuff. Less frenetic, the Efik singer/guitarist S S Peters offers a more laidback sound that is a credible precursor of the Efik highlife of Rex Lawson, as the notes suggest, along with the slightly more developed chord sequences of Etim Henshawís Nkpo Nnam Isuhoke Owo. I love the rasping bass voice that comes in on the chorus of this track, reminiscent of a South African groaner, rather than a highlife feature. At this early stage in the development of syncretic styles, separating the juju from the highlife from the palm-wine isnít always easy, and to me Godwin Scotland sounds like a juju artist. That might well just be my confusion, and in any case, it isnít to say that he doesnít belong here - distinct styles at this stage would still have been sorting themselves out, and the truth is that such distinctions are never as simple as all that anyway. Several of the ingredients that went to make up juju were also key to the development of highlife, even if the ultimate results might have sounded quite different.

Many of the most important Nigerian highlife artists of the later decades of the 20th century - like Oliver De Coque, Prince Nico Mbarga and Chief Stephen Osadebe - were Igbos. Recorded evidence of the early stages of this regional variant is, apparently, scarce, but the three examples included here are outstanding. The Ibo Youth Orchestra have already been mentioned, but the the other Igbo band here, Onitsha Native Orchestra offer my favourite track of all. In a collection in which every track is a highlight, Oje Mba somehow manages to stand out, for its haunting melody, its complex, elusive rhythms, captivating playing and beautiful vocals. Are those all guitars, or is there some kind of plucked idiophone (thumb piano) in there? Iím inclined to think so, although it doesnít seem to be included on the track that appeared on the other side of the original 78; a more familiar type palm-wine guitar song, which is almost as good. Also under-represented in the 78 catalogues were the musicians from Ifon in southwest Nigeria, but this compilation manages to include an excellent example from one of the few bands to have recorded in the period, the entirely obscure Ifon Aseko Players, whose Oba Imo Kawa is suddenly enlivened by a falsetto voice that pops up on the chorus.

Two tracks have no instrumental accompaniment at all, or just a little percussion, but just because we donít hear western instruments doesnít mean that weíre not hearing western-influenced music. I have no problem accepting that Etim Henshawís Wom Wom Si Wom is proto-highlife without the guitars or that Harry Taylorís Kini Nyana Bo Boma shows signs of the influence of Christian choral music, even if it sounds a world away from anything we might expect from church choirs in this country at this date. The recognition of these factors, of seeing beyond the obvious, seems to me a good sign of close understanding of the source material on the part of this compilationís producer. Mind you, the uniform excellence of the music throughout is a pretty good sign too.

In the midst of all these comparatively small-scale outfits (who nevertheless make the very most of their limited instrumental resources), Gold Coast Police Band, recorded in London in 1947, come as a bit of a shock, with their powerhouse brass-led rendition of Duke Ellingtonís Rocking In Rhythm. Whether they were working from a written orchestration, or a head arrangement derived from close familiarity with Ellingtonís own 1931 recording, they deliver a highly potent sound that the writer of the booklet notes speculates might be typical of the many brass bands that abounded in West Africa in the pre-war years. Those bands, unfortunately, left very little in the way of recorded sound evidence, although the booklet includes some tantalising photographs, but the two sides included here donít just function as a useful illustration of how such bands might have sounded. Rocking In Rhythm is a real treat, and Elmina Blues is even better: the brass arrangement is exciting and effective and this is unmistakeably a highlife record, with melodic echoes of E T Mensah, although a very different ensemble sound.

Also using brass instruments, and also unmistakeably highlife in orientation is Lagos Mozart Orchestra. E-san Inyong Ikide combines elements of the familiar Slide Mongoose/All For You melody, with that of Calabar-O (which Ambrose Campbell did record, most memorably, in London years later). The booklet notes give a useful potted history of the development of brass bands and their relationship with the colonial West African Frontier Force. You canít help wondering whether, as this bandís name suggests, they might also have played their own arrangements of classical pieces; it seems likely, given the bandsí role in relationship to the colonial community, but we can only imagine what such a thing might have sounded like.

If that last observation seems elegiac and regretful - a lament for another fugitive sound now lost forever - itís surely inevitable that such an emotion would be one of those evoked by a release like this one. But the fact that Delta Dandies exists at all is cause for festivity. I had almost given up hope of hearing much more of the kinds of music that I have known for years to have been recorded in West Africa in the inter-war years, but which has remained unreissued, and so unheard by any but the most fortunate of collectors. This album and its predecessor Awon Ojise Olorun have gone a long way to help assuage that particular craving, and the experience has been every bit as satisfying as I had hoped it would be.

The websites referred to in the review (also added to our Links section) are as follows:

Ray Templeton - 16.1.09

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |