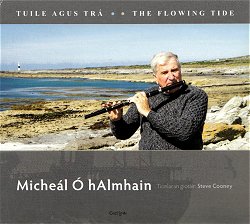

Tuil Agus Trá : The Flowing Tide

Gael Linn CEFCD 211

1. The Mother and Child / The Primrose / The Ivy Leaf (Reels); 2. Eilis Kelly's Delight / The Humours of Derrycrosane / The Rakes of Westmeath (Slip Jigs); 3. Speach MagUidhir / Allistrum's March (Clan Marches); 4. A'Ghrá luigh lámh liom (Fonn Mall); 5. Miss McCuinness / Gerdie Cumane's / Reenan's (Reels); 6. Dan O'Connell's Favourite / Moyglass Fair / Dan Sweeney's (Polkas); 7. The Cuckoo's Nest / Alexander's (Hornpipes); 8. Murtach MacCana / Lady Maxwell (Carolan's); 9. Now She's Purring / The Curragh Races / Poll an Mhadra Uisce (Reels); 10. The Humours of Drinagh / The Thrush in the Straw / The Mug of Brown Ale (Double Jigs); 11. Eibhhín Gheal Chiúin (Fonn Mall); 12. Comb your Hair and Curl it / The Dusty Miller / The Promenade (Hop Jigs); 13. The Cameronian / Humours of Loughrea / The Boys of the Hilltop (Reels); 14. Con Carthy's Favourite / Cat's Rambles to the Child's Saucepan / Jackie Daly's (Slides).

A native of south County Dublin now resident on Inis Oirr, flute player Micheál Ó hAlmhain has devoted his life to performing and promoting traditional music in Ireland through numberless sessions and teaching. This CD dedicated to his playing thus represents the culmination of a lifetime of musical activism and reflection. What first strikes the Irish music enthusiast is the unusually varied range of musical content and manner making up this selection. In contrast to the common fare of fast-and-furious reels with a few token jigs thrown in, only four tracks from fourteen are reels, the first of them taken at a gratifyingly gentle pace. Of the array of other tune types, the slow airs are flawlessly executed, the polkas and slides of evident Sliabh Luachra resonance are suitably scurrying, and the hornpipes are finely controlled. Less familiar is a pair of compositions by Turlough O'Carolan (track 8), revealing a wider reference than is usual among traditional musicians. There is also a beautifully articulated medley of double jigs (track 10), a time signature (6/8) whose rendering can easily be sluggish. In all this we are treated to a maestro parading his prowess across the gamut of materials, helping to keep in performance certain melodic species which might easily become extinct.

A native of south County Dublin now resident on Inis Oirr, flute player Micheál Ó hAlmhain has devoted his life to performing and promoting traditional music in Ireland through numberless sessions and teaching. This CD dedicated to his playing thus represents the culmination of a lifetime of musical activism and reflection. What first strikes the Irish music enthusiast is the unusually varied range of musical content and manner making up this selection. In contrast to the common fare of fast-and-furious reels with a few token jigs thrown in, only four tracks from fourteen are reels, the first of them taken at a gratifyingly gentle pace. Of the array of other tune types, the slow airs are flawlessly executed, the polkas and slides of evident Sliabh Luachra resonance are suitably scurrying, and the hornpipes are finely controlled. Less familiar is a pair of compositions by Turlough O'Carolan (track 8), revealing a wider reference than is usual among traditional musicians. There is also a beautifully articulated medley of double jigs (track 10), a time signature (6/8) whose rendering can easily be sluggish. In all this we are treated to a maestro parading his prowess across the gamut of materials, helping to keep in performance certain melodic species which might easily become extinct.

Of particular note in this connection are two sets in 9/8, under the variant headings of 'slip jig' and 'hop jig'. At the risk of tedium, not to say musicological naivety, the inclusion of these tunes extends an invitation to dwell on a lesser known time signature. Reg Hall, in his notes to Topic's Irish music set It Was Mighty!, offers a useful way in to the question: 'Contrary to what others have written, the hop jig and the slip jig are not the same thing; just compare the rhythm of Doherty's, a slip jig [CD1, track 12, Danny McNiff], and The Kid on the Mountain, a hop-jig [CD2, track 27, Michael Gorman in a Peter Kennedy recording of 1952]. The slip jig, a solo step-dance taught in the Irish dance academies, was an early twentieth-century Gaelic-revival invention. That isn't to say that traditional musicians didn't have tunes in nine-eight - they just didn't have a special dance to go with them.' (TSCD679T booklet, page 36. The last comment sits oddly against the testimony that both Michael Coleman and Michael Gorman - following Coleman - danced a hop jig to their own playing. See for example the booklet to Michael Gorman: The Sligo Champion, Topic TSCD525D, page 13. In addition, I have seen Kathleen Murray, a native of Gurteen living in London, perform a solo dance to The Promenade, a 9/8 tune played in the manner of a hop jig by Reg himself, outside The Favourite off Holloway Road. But this is incidental - dance is not the main determining dimension here.) This is an intriguing question badly stated. O'Neill's The Dance Music of Ireland: 1001 Gems includes a section of forty-odd 9/8 tunes under the heading 'Hop or Slip Jigs', which makes the point about the tendency to use the terms interchangeably. So is there tenably a qualitative distinction at work here?

The problem is best situated by reference to the customary division of 6/8 jigs (four beats in the bar) into 'single' and 'double', a separation observed by O'Neill. The single jig is formed characteristically of crotchet-quaver figures giving four notes in the bar (long-short, long-short), the double jig from triplets giving six notes in the bar (one-two-three, one-two-three). This distinction, of course, is emphatic not exclusive: most tunes in practice contain a mixture of the two figures. (Under single jigs, for example, O'Neill includes Lock the Door, which he renders predominantly in triplets.) In abstracto, a simple correspondence to this obtains in 9/8 (six beats in the bar): the equivalent to the single jig is the hop jig, the equivalent to the double jig is the slip jig. (The terminology is not hard and fast, but that is generally how the qualifiers are employed.) The crux of the whole question is that this apparent equivalence on the page becomes asymmetrical in performance. Accepting that the slip jig is built on triplets, a typical bar will contain nine notes. This means that for comfort it has to be taken sedately, allowing space for all six beats to be observed by an accompanist. In the crochet-quaver of the hop jig, conversely, a six-note bar is the norm, inviting a higher tempo to keep things from getting pedestrian, which in turn leaves time only to state three of the six beats in the bar. Where the effect of the first is akin to the double jig with extra beats, the second has the feel of a ravvivando waltz - misleadingly, in that the three beats in the vamp are not on-beat and two off-beats, but the three on-beats with the off-beats omitted through lack of elbow room.

These discriminations may be tested in recorded performance. A neat exemplification is provided by the first two tracks on Topic's 1963 EP, Irish Pipe and Fiddle Tunes, each indifferently designated 'slip jig': Hardiman the Fiddler, played by Willie Clancy, and Coleman's Favourite, played by Michael Gorman. The first is composed mainly of triplets and rendered at a moderate speed, while the second has the up-tempo, gustoso, pronounced three beats of the hop jig. A further instance incorporating these very tunes but this time employing the terminology is contained on Topic's LP Jimmy Power, Irish Fiddle Player (12TS306, 1976): Coleman's Favourite and The Promenade are hop jigs, Follow me Down to Limerick and Hardiman the Fiddler are slip jigs. The clinching example again comes from Michael Gorman, this time his Folkways Records LP with Margaret Barry (FW 8729, 1975), on which he couples The Kid on the Mountain - the very tune cited by Hall as emblematic of the hop jig - with The Mug of Brown Ale (Old Man Dillon), a 6/8 double jig, confirming the judgement that The Kid on the Mountain is a slip jig (9/8 triplets): if it were a hop jig, this combination could not run. In that sense, the tune is a badly chosen case. (Two incidental comments on this example of The Kid on the Mountain. Gorman had a sixth part not commonly heard but which is included by O'Neill. More pertinently, Michael Coleman's 1936 recording unintentionally tests the distinction at issue. In taking the tune at a high lick, the performance pitches between the two types: too fast for the conventional jig vamp, too slow for the three beats of the hop jig. His pianist instructively flails, veering between a scrambled six beats and a plodding three, not quite knowing how to solve the problem.)

There is, on this understanding, no example of a hop jig on either It Was Mighty! or It Was Great Altogether! The strange upshot of all this is that while it is possible to segue happily, unless the beats are being counted, from 9/8 of the triplet type into 6/8, it is not possible, more significantly, to string together two 9/8 tunes of the distinct types identified - for example, Hardiman the Fiddler and Coleman's Favourite - without perceptible rhythmic dislocation, even though both have to have six beats in the bar. These reflections surely confirm in practice the view that there is a capital qualitative difference at work here.

The main qualification to this verdict is that, in so far as the distinction is embodied in the manner of playing, it is contingent rather than categorical: does a hop jig acquire the character of a slip jig if it is rendered more slowly and thus vamped more busily? The Rocky Road to Dublin is a prime instance of 9/8 that may take either form. Pushing the point a stage further into internal properties, the defining crochet-quaver of the hop jig may be converted to a triplet by adding in a note, and conversely the triplet of the slip jig may be reduced to a crochet-quaver figure by dropping a note. In practice, of course, this would mangle the shape of the tunes as we have them, but it makes the point that structural characteristics are not necessarily immutable. In conclusion, it is less a matter of what is or is not the 'same thing' as of evolved habits of articulation which create the effect of a dissimilarity through performance. However this topic is glossed, it remains at the very least noteworthy that regular eight-bar melodies in the same time signature can have so substantially different a feel to them.

As illustrated by the Coleman example cited above, a key corollary to this melodic-rhythmic parsing is the problem of how these tunes should be accompanied, a test of comprehension in the playing. Backing throughout this disc is provided by guitarist Steve Cooney, whose efforts are highly-wrought, skilfully wrapping around the contours of the melody. Yet what in one respect is an exhibition of the accompanist's art is in another respect the art of learning nothing. Many a fine performer issued in the 1970s found their playing blighted by the twangling of a guitar or bazouki, a point made on the Celtic Grooves Imports site apropos recent reissues of John Vesey and Eddie Cahill. Gael Linn itself was responsible for one of the worst instances of this traducing on its 1982 LP of Julia and Billy Clifford: the playing of a mother and son in perfect rapport, among the finest of the Sliabh Luachra recordings, is muddled on six tracks by string backings which are as unrelated to this highly distinctive music as they could well be.

Much of what is served up on this disc is little better, clever arrangements jarring with, not to say distracting from, a form of music which is primarily melodious-percussive rather than harmonic. Most constructive is the plain, off-beat, slightly syncopated vamp applied to the lively reels of track 13, lending drive to melody playing which tends to err on the side of carefulness. The least successful accompaniment loops back to the hop jig question (track 12). Just where Micheál Ó hAlmhain produces some of his most urgent performance, the backing is at its most nebulous: in many passages, Cooney even marks all six beats, blurring the clean lines of the more usual three-in-the-bar. This is a round-about way of saying that Ó hAlmhain impressively grasps the niceness of the 9/8 rhythmic distinction whereas Cooney thrums across it, the point at which the understanding of soloist and accompanist is at its most divergent.

At the technical level, Micheál Ó hAlmhain is never less than in control of his instrument. His command of the long breath ensures he does not snatch at a tune; he employs occasional tonguing to separate out the notes of a phrase, as in The Boys of the Hilltop; and his fingers twiddle fluidly to produce the effects which are not bolted-on 'decoration' but abbellimenti integral to this musical idiom. Typically more measured than rousing, these performances would benefit from an enthusiastically baying audience to lift things a bit, but that is a problem built into studio recordings. All reservations aside, this is a carefully pondered production presenting an undisputed master's object lesson in what can be achieved in the right hands on a wooden pipe with six open holes, arguably the supreme embodiment of the capacity of ethnic musicians to turn to their own ends a piece of instrument technology intended for quite different use.

Andrew Bathe - 12.10.16

| Top | Home Page | MT Records | Articles | Reviews | News | Editorial | Map |