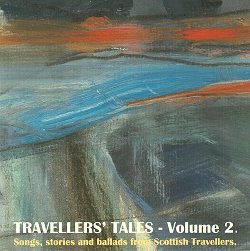

Travellers Tales, Vols 1 & 2

Songs, stories and ballads from Scottish Travellers

Kyloe Records - Kyloe 100 and 101

Volume 1:

Duncan Williamson: Johnny You're a Rover; The Lady and the Blacksmith; Bonny George Campbell; Conversation on Jack Tales; Story: The White Butterfly; Down in Yonder Bushes; Story: Jack Goes Back to School; Hind Horn. Stanley Robertson: Story: Hump-Back Jack; Tifty's Annie. William Williamson: The Dowie Dens o Yarrow.

Volume 2:

Stanley Robertson: Medley of Children's Songs; Story: Jack & The Three Jewels; Johnny o the Brine. Gabrielle Ijdo: Young Emslie. Duncan Williamson: The Trees Are High; Those Men of the Forest; John Barleycorn; The Golden Vanity; Queen Jane; The Butcher Boy; Fortune Turns the Wheel; Story: The Silkie's Revenge; Closing Our Camping Ground Down.

The first part of this review is going to be a fairly long discussion on who exactly the Scots travellers are. This is important to me in trying to investigate the relationship between their incredibly rich culture and the traditional separateness of the way they have lived. If you just want the review, can I suggest you follow this link.

The first question needs to be "Who are the Scottish travellers and where do they come from?"

Mike Yates provides two expanations in the notes to Volume 1:

In Scotland and Ireland, as well as in parts of Scandinavia, there are still to be found nomadic or quasi-nomadic groups whose way of life resembles that of the gypsies, although they have little or no gypsy blood in them. It is impossible to speak with certainty of their origin, but it seems likely that they are the descendants of a very ancient caste of itinerant metal-workers whose status in tribal society was probably high - Hamish Henderson

Since the Middle Ages in Scotland, travellers have been singled out as a special group of nomadic families set apart from settled communities by a habitual movement that, since World War II, no longer has been universally or invariably practiced. The travellers differ from both Romanies and the settled population, and may have their origins in a medieval Celtic tinsmithing caste, though this cannot be proven conclusively. In Gaelic they were known as cairdean, ironworkers who in ancient times went from clan to clan making weapons - James Porter & Herschel Gower

Well, read these and you can already see why we are struggling. Both these definitions from well-respected authorities talk about "castes" and I am not happy about that word being used in terms of Scottish society in the twentieth century. Certainly, the Scots travellers have historically thought of themselves as separate from the rest of society and they have been subject to horrendous abuse and discrimination by large parts of the urban population, though interestingly, they were more tolerated, if not appreciated, by isolated rural communities, but being in a "caste" implies something that has a semi-legal religious or cultural basis as it does in Hindu society.

If you would like to go further with more definitions of Scots Travellers and an in-depth analysis of their current problems and social status, I would urge you to read this review in conjunction with the Scottish Executive’s report entitled Moving On: A Survey of Travellers' Views which is available on the internet at www.scotland.gov.uk/cru/kd01/blue/moving-06.htm There they contribute two more useful definitions:

A nomadic group formed in Scotland in the period 1500-1800 from intermarriage and social interaction between local nomadic craftsmen and immigrant Gypsies from France and Spain in particular - Kendrick and Bakewell, 1995:10

Kendrick and Clark (1999) also refer to Scottish Travellers who claim earlier origins of "a tradition and culture which can be traced back to the nomadic hunter gatherers of ancient Scotland" (p.51).

Belle Stewart talked frequently about her family being descendants of the dispossessed Royal Stewarts from Jacobite times and there is often a basis of truth in such oral history, but I never read an argument that could make a convincing case for this. Sheila Douglas says:

Many of the travellers believe, as so do many non-travellers, that their forebears were the remnants of the scattered clans after Culloden, although their skills are much older than that. They were certainly not outsiders in Highland society. The clans themselves have an equally shadowy history and claim descent from legendary ancestors with whom their connection is based simply on oral tradition. But oral tradition is not an entirely unreliable source of information as their transmission of family history and story and song proves very clearly, confirmed by records. The practice of registering the birth of children, partly to get on parish registers for welfare and partly out of fear of bodysnatchers, makes it possible to trace the family trees of many travellers.

Thinking of The Stewarts of Blair, I turned to Till Doomsday in the Afternoon by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, thinking that they may have something to say on the subject. They avoid a definition, but they do contribute an insightful portrait of attitudes for this prominent Scots Traveller family:

That first meeting with the Stewarts was an exhilarating and memorable experience. It wasn't merely their warmth and friendliness which made the occasion unforgettable - it is the almost magical knack they have of making a stranger feel that he is returning to them after a long absence. There is no transitional stage in a relationship with them. One is accepted immediately into the family circle and, almost as quickly, into the wider circle of their many Traveller friends.

Our first impression was of a group of people joined together by immensely strong family ties, sharing common experiences, attitudes and possessing a dramatic sense which enabled them to transform the most trivial incident into an exciting event. Several years were to pass before we began to detect cracks in the family's apparent solidarity.

Exactly my experience with the Stewarts and other Scots Traveller families that I came to know. These people were social outcasts and somehow managed to be welcoming to a class of people who they knew had spurned them. They were poor but amazingly generous.

They are not generally taken for a separate racial type, as Romanies and Gypsies might be, and yet there are many broad-faced women particularly who seem to me to have that a typical Scots traveller look. However, we are talking about a relatively small number of intermarried families so that family resemblance may be what I am detecting.

Interestingly, the Scottish Executive website has some quotations from extensive interviews that show that like the Sussex travellers that I come into contact with through my work, they are trying to reclaim the once despised word 'Gypsy' and as a way of identifying themselves:

"What we hate is being classed as New Age Travellers, because we're not; we're Gypsies. We've travelled all our lives; we've been born and bred here - we've got roots," (Interview female)

"I think people get mixed up with all the New Age Travellers; they [New Age] give Travellers a bad name. They don't pay tax or anything; they just go up and down - they just don't want to work …they just give Travellers a bad name," (Female, Private).

The Scots travellers have their own cant and that, you would think, would indicate a racial type just as the Romany language show words from Indo-Arabic origins. MacColl and Seeger are helpful in drawing together the thinking on the origins of Scots traveller cant:

The vocabulary of cant is drawn from a wide variety of sources. In addition to hundreds of words borrowed from the artificially created thieves' jargon, there are archaic Gaelic words and phrases, debased Latin and French words, words borrowed from Romani, Arabic and half-a-dozen other languages and dialects. The Stewarts were insistent in pointing out that the vocabulary and pronunciation of cant shows considerable variation from district to district, and even from family to family.

There is little agreement among scholars when it comes to explaining the origins of cant. The one thing upon which they are all agreed is that it is of considerable antiquity.

The Scottish Executive report gives a fascinating if disturbing insight into the modern day lives of travellers, but you could search through the hundred and odd pages for a reference to their incredibly rich folk culture and the nearest you would get would be:

"Travelling's nae fun anymore; you used to be able to go - a few of you's the gether - and meet up wi' other people in the summer; you know enjoy the craic - have a laugh; but you just cannae dae that now. All that's finished," (Female)

Sheila Stewart would tell you that the cant is dying out rapidly and that the younger generation of travellers is generally disregarding the incredibly rich heritage of their ancestors. This makes these two albums all the more important - and yes I am going to review them.

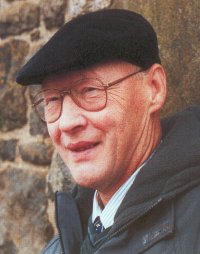

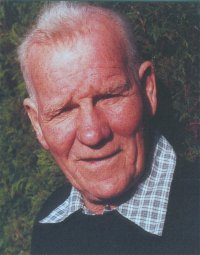

The two main contributors to these wonderful albums are two outstanding tradition bearers; Stanley Robertson of Aberdeen and Duncan Williamson, now of Ladybank in Fife. There is one song from one of Stanley’s daughters, Gabrielle Ijdo sings Young Emslie and another from one of Duncan’s sons; William Williamson sings The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow to his own guitar accompaniment. Otherwise it’s Duncan and Stanley who provide the fascinating lore.

The two main contributors to these wonderful albums are two outstanding tradition bearers; Stanley Robertson of Aberdeen and Duncan Williamson, now of Ladybank in Fife. There is one song from one of Stanley’s daughters, Gabrielle Ijdo sings Young Emslie and another from one of Duncan’s sons; William Williamson sings The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow to his own guitar accompaniment. Otherwise it’s Duncan and Stanley who provide the fascinating lore.

The booklet only has space for short biographies of the pair, so let’s fill out things a little. Stanley was born in 1940 and comes from the famed Aberdeen travelling family. His aunt was Jeannie Roberson and his cousin was Lizzie Higgins and a lot of his songs, ballads and singing style come from them. As well as a singer, Stanley is a piper and a remarkable storyteller. Many of the stories came from his maternal grandfather, Joseph Edward McDonald. He lived in the house with the family when Stanley was young. Joseph was born in England and claimed that his real name was Brookes although he always seems to have been known as McDonald. As a young man left his family when he was quite young and travelled with a circus looking after horses. Stanley thinks that it was at this time of his life that he learned many of his stories.  He was also a highly regarded ballad singer. Stanley’s piping was mostly learned in his seven years in the Territorial Army.

He was also a highly regarded ballad singer. Stanley’s piping was mostly learned in his seven years in the Territorial Army.

Stanley’s life has been mostly spent in houses apart from some "summer walking". Mostly he has worked in Aberdeen Docks as fish gutter; he once worked alongside Lizzie. It becomes very obvious after only a few minutes talking to Stanley that you are in the company of a perceptive, intelligent, sensitive person, fiercely proud of his heritage and yet one who never found fulfilment for these talents in his working life. Ian Russell says, "Owing to the prejudice against travelling people he has never been able to obtain a job commensurate with his abilities; after various jobs in the fish trade he became a 'smoker and filleter', and this is still his regular occupation."

To my mind, Stanley is an outstanding singer, but I have been in arguments with those who do not agree. True, he lived in the shadow within his family of two of the greatest traditional singers that Scotland has produced, but Stanley is a very worthy inheritor of that great tradition. It may be that this reaction to his singing in some places in Scotland that made Stanley turn to his other great skill, his storytelling.

He has produced several books of his traditional stories. Mike lists them as:

- Exodus to Afford. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1988

- Nyakim's Windows. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1989

- Fish Hooses. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1990

- Fish Hooses - 2. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1991

- The Land of No Death. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1993

- Ghosties and Ghouties. Nairn. Balnain Books. 1994

Plays by Stanley Robertson:

- Scruffy Uggie. Performed Aberdeen, 1997

- Jack and the Land of Dreams. Performed Edinburgh 2000

He was adopted by the North American academic community in the 1970s and was invited to lecture on, and tell his stories and various schools, colleges, universites and cultural conferences and events in Canada and the USA. It has only been in very recent times that Aberdeen University seems to have realised that it has such a giant of the Oral Tradition in its midst (and I’m sure that this is not unrelated to the fact that Ian Russell has now joined their staff). The university’s Elphinstone Institute, supported by Lottery funding, has appointed him to their staff. His brief will be to conduct a study of the travellers’ traditions ‘from the inside’. Their website says that "As an acknowledged expert and member of the Traveller community, Stanley will document his own lore and that of other members of this group, and promote the cultural traditions of Scottish Travellers among young people, in schools and community groups, including young Travellers … The project aims to raise the awareness of children and young people to the rich heritage of Traveller traditions, especially through interactive workshops of song and story, and to document and record  Traveller oral and cultural tradition, including songs, ballads, stories, language, customs, beliefs, occupations, family life, and in general their contribution to society."

Traveller oral and cultural tradition, including songs, ballads, stories, language, customs, beliefs, occupations, family life, and in general their contribution to society."

Duncan’s life has generally been better documented in that he has published his autobiography (The Horsieman - Memories of a Traveller 1928-1958. Canongate Press, Edinburgh ISBN 0 86341 444 X) He was born in a tent on the shores of Loch Fyne, one of sixteen children, and his book, transcribed from 30 hours of reminiscences on tape gives one of the best insights into travelling life that exists.

His first marriage was to his cousin Jeannie Townsley and during that time he continued the travelling life in the same area as his parents and grandparents and it was at that time that he first came into contact with the School of Scottish Studies and The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland. At that time Duncan presented himself in a very much as a typical product of his background. We heard him more as a singer than as a storyteller in those early TMSA festivals. His style was to change after his subsequent marriage in 1976 to Linda Headlee, an American academic from The School of Scottish Studies. It was collaborating with her that enabled him to produce his books which are (Mike’s list again) :

- Fireside Tales of the Traveller Children. Edinburgh. Canongate, 1983.

- The Broonie, Silkies and Fairies: Traveller's Tales. Edinburgh. Canongate, 1985.

- Tell Me a Story for Christmas. Edinburgh. Canongate, 1987.

- A Thorn in the King's Foot. Folktales of the Scottish Travelling People. Harmondsworth. Penguin Books, 1987.

- Don't Look Back, Jack! Edinburgh. Canongate, 1990.

- The Genie and the Fisherman, and Other Tales from the Travelling People. Cambridge CUP. 1991.

- The Horsieman: Memories of a Traveller 1928 - 1958. Edinburgh. Canongate, 1994.

- Rabbit's Tail. Cambridge. CUP. 1996.

- The King and the Lamp: Scottish Traveller Tales. Edinburgh. Canongate, 2000.

Like Stanley, Duncan found an appreciative reception for his skills amongst the American academic institutions and this and his books have contributed to his current stature as a storyteller in Britain.

Having known their storytelling from the time before their stories before their tales were published and before they became used to an academic audience, it is possible for me to comment on the changes that have taken place in the delivery of their stories. Generally, the style has become more accessible; words in cant have more or less disappeared from their performances. Duncan’s style has the more obvious changes. His accent is less thick. He will introduce and contextualise his stories before launching into the main body of the story and he will explain words that he feels will not be understood ("And ‘weans…’; he called us ‘weans’; that’s an old Scottish word for children.) However, this all tends to be towards the beginning of his stories and by the time that he is in full flow,  he is every bit the master story teller he always was. By the time he is well into The Butterfly, (sound clip) the accent is back, he uses repetition and the rise and fall of his voice and variation of pace to great effect. It is entrancing stuff. This and The Selkie’s Revenge are probably the most listenable of Duncan’s stories, but he creates a spell with every story.

he is every bit the master story teller he always was. By the time he is well into The Butterfly, (sound clip) the accent is back, he uses repetition and the rise and fall of his voice and variation of pace to great effect. It is entrancing stuff. This and The Selkie’s Revenge are probably the most listenable of Duncan’s stories, but he creates a spell with every story.

The changes in Stanley’s delivery style are less obvious and more subtle. One of his great strengths has always been the impact of the start of his stories.

He quickly establishes the slow deliberate pace, uses pauses to great dramatic effect and with the immediate ability to command attention and to control the changing moods of his stories (sound clip). The changes are in the extended vocabulary that he now uses, ("So he lived on a’ the wee fungi…." ) ("An’ the king had a wizened face; decrepit-looking." ) words and phrases that might not have been used in these stories forty years ago. This does not alter the all-engaging delight of the stories presented here. In Jack and the Three Jewels and Hump-Back Jack both over a quarter of an hour long, we have the mesmerising traveller story-telling at its very finest.

He quickly establishes the slow deliberate pace, uses pauses to great dramatic effect and with the immediate ability to command attention and to control the changing moods of his stories (sound clip). The changes are in the extended vocabulary that he now uses, ("So he lived on a’ the wee fungi…." ) ("An’ the king had a wizened face; decrepit-looking." ) words and phrases that might not have been used in these stories forty years ago. This does not alter the all-engaging delight of the stories presented here. In Jack and the Three Jewels and Hump-Back Jack both over a quarter of an hour long, we have the mesmerising traveller story-telling at its very finest.

There are equal delights to be found in the singing on these albums though this is more variable in standard than the story-telling. Gabrielle Ijdo is not the first of Stanley’s daughters that I have heard performing. I’m afraid that none of them can hold a light to Jeannie, Lizzie or Stanley. It is interesting to hear one song from her, Young Emslie, but it is also disappointing. She has difficulty holding the tune and there is nothing that suggests that she would ever reach the standard that we have heard elsewhere in the family.

William Williamson is a more interesting singer as his contribution of the Dowie Dens of Yarrow shows he has a lighter voice than his father, but here he sings to a strummed guitar accompaniment which dominates the timing. The result is of a quite good floor-spot standard. It would be interesting to hear him recorded unaccompanied. However, all the interest really lies with the two main contributors.

The track listing shows that Duncan has the lion’s share of the singing here. Some of the songs must be regarded as having a dubious place in a travellers’ repertoire. The Lady and the Blacksmith, by the time it settles down, is more of less the famed Martin Carthy version of The Twa Magicians and Martin tells us in sleeve notes that "the tune was fitted to the (anglicised) words by A L Lloyd." This is going to matter to those people who take a purist view of a traditional singer’s repertoire and it does make one wonder how many of the other songs could have come from revival sources - possibly Bonny George Campbell and Those Men of The Forest from their tunes.

Some of Duncan’s commanding performances are a real tour de force. Probably the most impressive is at the end of the first album with Hind Horn, although he has probably pitches the very fine The Golden Vanity and Queen Jane rather better for his voice.  However his singing is probably at its most enjoyable in some of the short fragments that are included;

However his singing is probably at its most enjoyable in some of the short fragments that are included;  there are only a couple of verses to Down in Yonder Bushes but it sees Duncan at his gorgeous best (sound clip).

there are only a couple of verses to Down in Yonder Bushes but it sees Duncan at his gorgeous best (sound clip).

We get rather less of Stanley’s singing, but what we do get is beautiful. On this evidence, (though not always with him) it is Jeannie Robertson’s influence that dominates. Stanley sings a very full version of Tifty’s Bonnie Annie in a slow and stately style - full of swells and emphases.  Fifteen minutes of one ballad will be too long for many ears, but this pair remains riveted by performances like these. A similar treat is on offer with his Johnnie o’ the Brine (sound clip). Then there is a medley of children’s songs. I could have done with a much higher proportion of Stanley’s superb singing voice, but he is well served by Mike’s recordings here and a solo album of Stanley’s singing would be an excellent future project for the admirable Mr Yates.

Fifteen minutes of one ballad will be too long for many ears, but this pair remains riveted by performances like these. A similar treat is on offer with his Johnnie o’ the Brine (sound clip). Then there is a medley of children’s songs. I could have done with a much higher proportion of Stanley’s superb singing voice, but he is well served by Mike’s recordings here and a solo album of Stanley’s singing would be an excellent future project for the admirable Mr Yates.

Mike has had many of his recordings in Britain and North America issued on a variety of labels but, as far as I know, these are the first CDs that he has released himself. His first brace on Kyloe gain top marks.

Vic Smith - 5.11.02

PS: Something happened in preparing this review that I never thought would happen - I found a slight mistake in the writings of Mike Yates, that most careful and meticulous of researchers. The article on Duncan Williamson is in issue No. 33 of Tocher, not No. 30 as it says in Mike’s notes. Now, do I qualify for my anorak?

PPS: Musical Traditions Records are now supplying both these CDs, price £12.00 each. Details and Order Form on the Records page.

Site designed and maintained by Musical Traditions Web Services Updated: 26.9.03

The two main contributors to these wonderful albums are two outstanding tradition bearers; Stanley Robertson of Aberdeen and Duncan Williamson, now of Ladybank in Fife. There is one song from one of Stanley’s daughters, Gabrielle Ijdo sings Young Emslie and another from one of Duncan’s sons; William Williamson sings The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow to his own guitar accompaniment. Otherwise it’s Duncan and Stanley who provide the fascinating lore.

The two main contributors to these wonderful albums are two outstanding tradition bearers; Stanley Robertson of Aberdeen and Duncan Williamson, now of Ladybank in Fife. There is one song from one of Stanley’s daughters, Gabrielle Ijdo sings Young Emslie and another from one of Duncan’s sons; William Williamson sings The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow to his own guitar accompaniment. Otherwise it’s Duncan and Stanley who provide the fascinating lore.

He was also a highly regarded ballad singer. Stanley’s piping was mostly learned in his seven years in the Territorial Army.

He was also a highly regarded ballad singer. Stanley’s piping was mostly learned in his seven years in the Territorial Army.

Traveller oral and cultural tradition, including songs, ballads, stories, language, customs, beliefs, occupations, family life, and in general their contribution to society."

Traveller oral and cultural tradition, including songs, ballads, stories, language, customs, beliefs, occupations, family life, and in general their contribution to society."

He quickly establishes the slow deliberate pace, uses pauses to great dramatic effect and with the immediate ability to command attention and to control the changing moods of his stories (sound clip). The changes are in the extended vocabulary that he now uses, ("So he lived on a’ the wee fungi…." ) ("An’ the king had a wizened face; decrepit-looking." ) words and phrases that might not have been used in these stories forty years ago. This does not alter the all-engaging delight of the stories presented here. In Jack and the Three Jewels and Hump-Back Jack both over a quarter of an hour long, we have the mesmerising traveller story-telling at its very finest.

He quickly establishes the slow deliberate pace, uses pauses to great dramatic effect and with the immediate ability to command attention and to control the changing moods of his stories (sound clip). The changes are in the extended vocabulary that he now uses, ("So he lived on a’ the wee fungi…." ) ("An’ the king had a wizened face; decrepit-looking." ) words and phrases that might not have been used in these stories forty years ago. This does not alter the all-engaging delight of the stories presented here. In Jack and the Three Jewels and Hump-Back Jack both over a quarter of an hour long, we have the mesmerising traveller story-telling at its very finest.

there are only a couple of verses to Down in Yonder Bushes but it sees Duncan at his gorgeous best (sound clip).

there are only a couple of verses to Down in Yonder Bushes but it sees Duncan at his gorgeous best (sound clip).